Résumé

Dans une séquence pédagogique fondée sur une étude de cas et un jeu de rôle critique, nous cherchons à sensibiliser les étudiants et les étudiantes de licence en Langues Etrangères Appliquées aux transitions et transformations induites par l’intelligence artificielle. Ces transitions ont des dimensions sociétales, éthiques, technologiques et écologiques. La séquence explore l’économie, les start-ups et les personnalités de Silicon Valley afin d’interroger les usages, les processus de décision et les environnements professionnels liés à l’IA.

Mots-clés : pédagogie, IA, jeux de rôle critiques, approches critiques de discours, multimodalité, narrative, étude de cas

Abstract

In a teaching sequence based on a case study and critical role-play, we seek to raise Applied Foreign Languages undergraduate students’ awareness of the transitions and transformations brought by artificial intelligence. These transitions have societal, ethical, technological, and ecological dimensions. The sequence explores the economics, start-ups, and personalities of Silicon Valley in order to question uses, decision-making processes, and professional environments linked to AI.

Keywords: pedagogy, AI, critical role-play, critical discourse, multimodality, narrative, case study

Texte

Introduction

With the rise of artificial intelligence (AI) tools, questions about their societal role and technological, ethical, and ecological implications are receiving increasing attention. As these tools become more prevalent across various professional sectors, concerns arise not only about their impact on the nature of work, but also on essential skills, such as decision-making, critical thinking, or creativity. For instance, according to the 2024 Work Trend Index Annual Report by Microsoft and LinkedIn[1], 71% of sector leaders state that they would prefer to, “hire a less experienced candidate with AI skills rather than a more experienced candidate without them”[2]. It is, therefore, crucial to encourage pedagogic reflection on how AI tools are now integrated into professional and pedagogic practices and on striking a balance between how they can facilitate complex tasks, and, “liberate workers from menial work and enable innovation and creativity to flourish”[3] whilst trying to avoid over-reliance. Such over-reliance can translate, in the workplace, as over delegation of editing and creative functions[4], or, at university, in adoption of practices[5] that are, essentially, plagiaristic.

This pedagogic testimony presents a teaching sequence designed for French undergraduate Applied Foreign Languages (LEA) students, that aims to assist in equipping these students to engage critically with AI technologies by bringing them into the class in order to examine their use, the key personalities and companies associated with them, and better understand their (dis)advantages. In the sections that follow, we begin, firstly, by outlining the theoretical and pedagogical foundations for our sequence, focusing on the role of counter-narratives and critical role-play case studies in the language classroom and in LEA/LANSAD[6] contexts. Secondly, we describe the implementation of our teaching sequence, structured around the technological, ethical, and ecological transformations associated with AI. Thirdly, we discuss questions of evaluation related to the sequence and to student productions, and some initial findings.

Critical pedagogies

One aspect of professional courses, like LEA/LANSAD, is the design of teaching and learning environments that enhance students’ critical thinking, among other soft skills, in order to make them as competitive as possible in today’s labour market. AI and its almost unlimited potential for multimodal generation and synthesis has dynamited discussions about critical thinking. Two distinct schools of thought are emerging: one emphasises the possible added value, particularly for businesses, in critically using generative AI, whereas the other notes its limitations and the dangers of uncritical over-reliance[7] [8] [9]. These camps are associated with different narratives of technological progress. The GAFAM (Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon, and Microsoft) or the ‘Magnificent Seven’ (Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta Platforms, Microsoft, NVIDIA, and Tesla) through communications, product releases, and market orientation, promote narratives that generally advocate for screen culture, and the objectification of knowledge and ontology. Against these ‘dominant’ narratives, counter-narratives circulate as, “stories which people tell and live which offer resistance, either implicitly or explicitly[10]”.

Counter-narratives may be harnessed in pedagogy to both more beneficially and multidimensionally understand new technologies and offer resistance to potentially harmful or constrained ways of working, learning, and being a student. ‘Dominant’ cultural narratives are circulated by those in power. They are what Gee[11] refers to as ‘big D’ discourses, or what Lyotard and Brügger[12] define as ‘grand’ narratives. Kölbl[13] offers an interesting qualification of the term, noting that it may refer to, i) the version of a narrative that is most common, ii) a discourse or ideology that has become naturalised, iii) a narrative that is unequally distributed among divergent population groups, or iv) a particular way of talking that impacts on the structure and function of narratives.

There are, consequently, many ways in which people can resist dominant narratives: i) through composing alternate versions of a narrative – versions that advance distinctive plots and protagonists, ii) denaturalising discourses and ideologies and, on the contrary, drawing attention to the contradictions and ill-desired outcomes of these big D framings, iii) redrawing cultural and group-related boundaries and sharing narratives and, finally, iv) being aware of the language one draws on to tell a story. OpenAI itself can be used as an example. The dominant narrative of the company, voiced by Sam Altman, is that of a pioneer working to ensure that AI benefits all of humanity; a narrative frequently echoed in media and institutional discourse. This narrative has become so common that it conceals specific choices and values that shape the path taken. It can be denatured by identifying and deconstructing the techno-solutionist ideology, which highlights the importance of rapid AI development as essential to outpace potential threats, and its silence with respect to ecological issues. In addition, while AI is beneficial for developers, policymakers, or investors, it also disempowers precarious workers, educators, students, etc. These different groups can, similarly, be identified and aligned with. Finally, the very language used by OpenAI, that is full of technical abstraction, specialised jargon, conditional futurity, and utopian promise, structures its discourse in ways that delay critique. This language can be analysed for person deixis, connotation, and modality as one would do for simple critical discourse analysis (CDA)[14] and thereafter reframed or retold. These are, however, discursive and identificatory, rather than technological, insights, and it is very important to the design of our language course that the very tools of OpenAI, such as ChatGPT, can be used to engage with these narratives, critically understand them, and advance possible counter-narratives.

The objective of our pedagogical sequence is twofold: we seek both to enhance students’ critical thinking and creativity, and to raise their awareness of the advantages, dangers, and ethical, societal or environmental issues associated with AI. Our motivation lies in the idea that as educators, we have to prepare our students for their future professional paths, and whether we like it or not, society is undergoing significant transitions and transformations induced by various technological advances, in the AI sphere in particular. The report by Microsoft and LinkedIn[15], based on the answers of 31,000 people from 31 countries, reveals that 75% of workers use AI to save time, to focus on their most important work, to be more creative, in other words, “to not just work faster, but to work smarter”[16]. The report notes that AI is not necessarily replacing or eliminating jobs, but transforming existing ones and creating new ones.

In language-related jobs, like the ones our LEA students are most likely to have, such transformations are quite significant. LEA Students are wondering whether there is still a need to master foreign languages, whether jobs in translation are going to exist in the future, whether they chose the right bachelor’s programme, and whether the skills and knowledge they have acquired, and are still acquiring, are going to be relevant. Hence, it seems only logical to offer relevant and professionalising courses to our students to make them aware of such transformations and, thus, begin the conversation on how to knowingly use AI tools. Integrating AI into our classes is a way for us, as language teachers, to discover our students’ AI-related practices and to moderate their fears or excessive enthusiasm, by guiding them through the advantages and limitations of such technologies.

Given the objectives of our teaching sequence, we choose to use role-plays and case studies, two teaching techniques that align with the literature on foreign/second language teaching and learning, including English and English for Specific Purposes (ESP)[17] [18]. These techniques also comply with the recommendations of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages to implement an action-oriented approach in foreign/second language education. Both role-plays and case studies are particularly appropriate for use in LEA/LANSAD teaching and represent an added value in such fields as they mimic real-life communication and close-to-authentic professional situations: i) they allow for group work and pair work, which introduces differentiation into the class and increases student output by promoting learning by doing, ii) they foster a less stressful environment for students who struggle with face-to-face interaction, iii) they tap into soft skills (time management, collaborative work, creativity, problem-solving, risk-taking, analytical and critical thinking) that are essential for students’ professional and personal development, and iv) they help develop students’ language and linguistic skills[19]. Given these advantages, it seems only logical to combine these two techniques and base a role-play on a case study.

Case studies have interesting pedagogical origins. In the early 20th century, Harvard Law School, followed closely by Harvard School of Business, began regularly integrating the case study approach. Since then, other universities and faculties have adopted it to teach diverse subjects, including social sciences, mathematics, chemistry, and foreign/second languages. Owing to its close ties to disciplines such as law, economics, management, etc., the approach appears especially appealing for teaching foreign languages in LEA/LANSAD departments. However, it is worth mentioning that its success largely depends on whether the selected case is both relevant and timely, whether the medium (paper vs online materials) is engaging, and whether the case structure (open vs closed) encourages students to rely solely on teacher-provided materials, or explore various other resources they deem necessary to solve the problems presented[20].

Role-plays have been widely used in humanities-focused disciplines, social sciences and hard sciences. Initially associated with, “the early days of the communicative approach”[21] to teach foreign/second languages, they received strong criticism in the 1990s, after which their use declined significantly[22]. The concept of role-play encompasses a variety of teaching possibilities. As Shapiro and Leopold[23] point out, they involve, “some kind of role and some sort of play.” They can be applied at different educational levels (elementary and secondary schools, tertiary institutions, lifelong language learning courses[24]) and for various pedagogical purposes (e.g., to develop receptive or productive language skills, to enhance linguistic competence, to build soft skills, and to familiarise learners with specific contents, etc.). Hence, when designing role-plays, practitioners should strive to engage learners in a way that guarantees, “cognitive challenge while still creating the conditions for improved linguistic competence”[25]. The adjective “critical,” placed before “role-play,” refers to the idea that the latter preferably aims to allow students to, “embody voices and perspectives that may be quite different from their own” [26] or from the mainstream (i.e., dominant, naturalised, big D).

Role-plays and case studies have recently faced criticism due to concerns that students might be tempted to delegate some tasks to AI tools, especially given that these tools tend to perform better when prompts specify a role for the AI to assume[27] [28]. However, AI’s good performance does not deprive such teaching approaches of their relevance. When properly designed, they can actually offer an opportunity to reflect on the added value of human intelligence and, in contradistinction, the temptation to outsource analytic work, questions of intellectual property, plagiarism, authorship, and integrity. In our teaching sequence, we invite students to carry out most of these tasks in the classroom, under teacher supervision, which encourages students to use AI responsibly and reflectively. Moreover, these two approaches are beneficial not only for students, but also for instructors. AI tools have a latent transformative pedagogic potential, in helping teachers conceive scenarios for role-plays and case studies where the accent is on student creativity, critical thinking, and ethical awareness[29].

Taking into consideration the aforementioned elements, we have decided to design our role-play around the highly debated topic of AI by exploring alternative narratives about its use. We aim to challenge the narratives that are commonly circulated in professional circles, and thereby foster students’ critical awareness of AI-mediated language, both professionally and educationally. We use critical role-play in the context of a case study focused on key figures and enterprises in Silicon Valley. Our teaching materials guide students through an exploration of Sam Altman’s ethics and the reasons for his initial dismissal from OpenAI, while also encouraging broader reflection on current discourses surrounding AI, such as those embodied by Elon Musk or Alphabet, so that students learn to question and critically assess them.

The teaching sequence

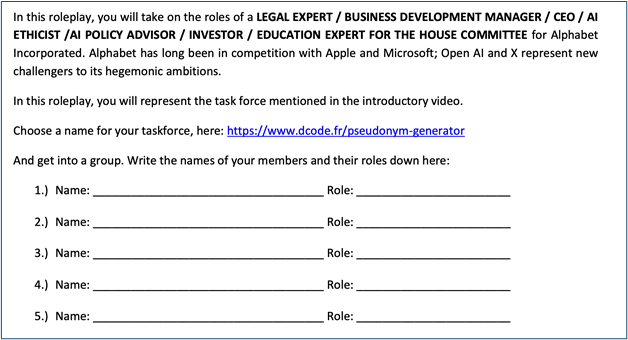

The teaching sequence is designed to cover half a semester, with pre- and post-sequence activities. It is intended for third-year LEA students who are expected to have achieved a B2–C1 level of the CEFR. There is a strong emphasis, in the sequence, on multimodality and computer-assisted reading and writing. The lexical elements that we wish to emphasise are those concerned with identity and personal style, the stock market and economic environment, and, crucially, the sector of AI and audit. In our critical role-play scenario, students take on specific roles within a fictive specialised task force at Alphabet Inc., whose aim is to protect the company’s position in the competitive AI landscape. This is done by leading a multifaceted investigation and assessment of the risks and benefits associated with AI, by considering recent controversies, ethical issues, and economic threats and opportunities. As members of this task force, students contribute to developing a plan for Alphabet’s future in the field (Fig. 1) which naturally touches on technological, ethical, and ecological considerations.

Fig. 1 – Instructions for the role-play and group creation phase

Session 1 of the sequence establishes a base-line in terms of students’ knowledge of AI tools and their knowledge of key personalities and enterprises of Silicon Valley. It is accompanied by an online questionnaire, consisting of ten open-ended items, that seeks to quantify data on student appreciations and attitudes:

- When you hear ‘AI’ what comes to mind?

- How many AI tools have you tried?

- Which AI tools have you tried?

- Do you use AI tools? If so, which ones?

- Explain the steps you would have to undertake if using an AI tool to revise/write a text.

- When do you use them? Why?

- What do you like about using AI tools?

- What do you dislike about using AI tools?

- Do you think AI tools perform better or worse than humans?

- Do you think it’s right to use AI, and why?

Session 2 makes use of an AI-generated video to introduce group work in a meaningful way and assigns group roles (business development manager, policy advisor, etc.) based on research into real-world corporate structure. The reasons for generating the introductory video with the help of AI are to diversify the modality of teaching materials and task instructions, typically presented in written form, and to simulate a real-life situation with tailor-made information. This reinforces the emphasis on role-playing. The session also requires students to film and share their research into the risks and benefits of AI – it is a first task on the theme that is deepened in subsequent sessions.

Session 3 delves into the biographies of key personalities of Silicon Valley (Brockman, Pichai, Page, Nadella, Musk, Zatlyn), and draws a (Myers Briggs) psychological profile based on research and a class debate.

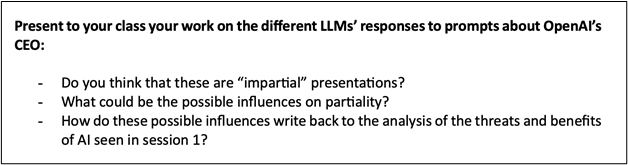

This session also looks into how Large Language Models (LLMs) have pre-established filters and hidden ideological coordinates, by requiring students to critically compare texts generated by two or more different LLMs in response to prompts about Sam Altman, thus reflecting on these platforms’ impartiality or lack thereof (Fig. 2). Students again film and share their research, taking on different group roles, with the aim of creating close-to-authentic professional situations and mimicking real-life communication.

Fig. 2 – Instructions for the LLM responses’ comparison activity

Session 4 uses Open AI as a case study in order to explore start-up market capitalisation. This leads to questions of share price and market fluctuation. Shareholder demands are compared to the text by Kate Raworth on the ‘doughnut’ of safe and just development[30].

Session 5 begins the task of preparing the group submission to the class that may include video or AI-generated multimodal texts. The brief aims to move from students’ knowledge of the sector to an informed appraisal of policy (Fig. 3).

Session 6 provides an opportunity for the groups to present their reports.

As mentioned previously, using AI tools is not forbidden in task instructions, given that one of the teaching sequence’s aims is to guide students to consider the transformations to tasks brought about by AI. Following the sequence, there is a questionnaire that aims to measure the increase in student awareness of AI-related issues and any resulting change in appreciations and attitudes.

Fig. 3 – Instructions for the final role-play report

From the above summary of the teaching sequence, one can appreciate three separate, but complementary, axes: technological, ethical, and developmental/ecological. The technological axis concerns knowledge of LLMs, their different uses and biases, and research into Silicon Valley’s corporate and economic functioning. The ethical aspect concerns the bases for the decisions made by key personalities in the AI sector, the increasing power of tech giants over our lives and intimacies, and the ethics of use of AI tools. Finally, the developmental/ecological aspect covers the capitalisation of these kinds of startups, but also the environmental impact of the LLM value chain, with an emphasis on the energy implications of blockchain technologies. This last axis extends to Altman’s other projects, such as his WorldCoin cryptocurrency, or recent start up with Jony Ive, the designer of the iPhone. In inquiring into these questions, students can rely on a huge amount of both scientific and journalistic sources that span the period from ChatGPT’s unveiling to recent incognitos and suspicions.

Questions of evaluation and some initial findings

To evaluate the sequence in pedagogical terms, we have designed a multi-layered approach that includes pre- and post-questionnaires, three in-sequence evaluations, and class observation. The pre-questionnaire consists of ten open-ended items, discussed above, whose goal is to gather information on students’ awareness of the AI sector. The post-questionnaire contains the same ten open-ended items, rephrased, and five Likert-scale items to assess students’ perceptions of the sequence in terms of both knowledge/competence acquisition and motivation. Comparing students’ responses to the open-ended items in the pre- and post-questionnaires offers insights into whether and how the sequence has influenced their awareness of AI. Student motivation may also be evaluated through class observations.

These measures are completed by in-sequence assessment of oral and written output. Students record videos (to be posted on Padlet or open access alternatives like Digipad[31] [32]): in the first one, they outline the risks and benefits of AI, and in the second one, they share their conclusions concerning the answers provided by ChatGPT and one other LLM to a prompt asking to describe Sam Altman. For the third in-sequence evaluation, students produce either a written or a video report proposing a strategic roadmap for Alphabet Inc. to navigate current AI controversies and remain competitive in a rapidly evolving tech landscape (Fig. 3). This is particularly pertinent in a post-Deepseek, post-Trump, environment that was able to knock a third off Nvidia’s share value in a weekend. Students’ video tasks and their final report are to be evaluated from several angles: critical and analytical thinking, acquisition of specialised AI-related knowledge, including linguistic means, like AI- and technology-related terminology, employed to engage with or convey it, as well as creativity in proposed solutions and reflections, such as stylistic features, irony, metaphors, figurative language, word coinage, and creative technological solutions to make videos.

Preliminary pedagogical findings would suggest that students have a task-based approach to AI, using it to condense readings, isolate arguments and analyse data, or even to create quizzes based on their course notes and thus facilitate learning in preparation for class tests or presentations. This is not to overlook less appropriate uses of AI, such as delegating the writing of assignments. They have already incorporated AI into their study habits and LLMs are, de facto, an integral part of the university’s academic ecology. Additionally, students have a generally positive attitude towards AI and recognise the strengths of LLMs in comparison to other, previous, knowledge distribution systems, such as Wikipedia or browser searches.

However, findings seem more mitigated when it comes to critical appraisal of the results that LLMs generate. Students seem to lack the personal general knowledge (historical dates, places, authors, concepts) that would allow them to accurately appraise the reliability of a return. They also seem to not understand the business model that is behind big tech generally and LLMs in particular. Their use of AI is, as a result, a curious mixture of worldliness and naiveté. They, for instance, do understand the economics behind paywalls, and accuse LLMs of being, “more stupid now than they used to be” in reference to OpenAI requiring more prompts of free users than they do of pro users. However, larger questions of knowledge economies and the benefits that can accrue to companies that control information seem not to have occurred to them before the sequence. There is, as a result, space, and need, for a teaching sequence such as this in their university curricula.

In-sequence assessment supports other preliminary findings. Student video tasks are creative in the chosen format (e.g., journalistic interview; testimonial type documentary) and in video editing choices (e.g., appropriate background music, hidden faces for anonymity). While some groups are motivated by their Alphabet Inc. roles as provided within the role-play (legal expert, education expert, business development manager, investor), and are keen to adopt them as part of the risks and benefits video, others add different yet relevant roles to illustrate their arguments and create contrast. These may be, for example, i) a radiologist to testify on the benefits of AI in the medical field vs. a translator who exposes the risks and dangers for the profession, or ii) a successful and rich individual who made their fortune through AI vs. a victim of financial fraud through the use of deepfake. The portrayals of these roles are complemented with details that allow them to contrast AI’s roles in different parts of the world (e.g., India and the United States). Setting up and encouraging fictional yet realistic professional roles from the outset seems to allow students to take a step back from the narratives, which circulate in their sphere, and put forward more critical statements on AI’s societal role. The details they add (professional and geographical coordinates) show a budding awareness of more specific facets of AI according to the aforementioned technological, ethical, and ecological dimensions.

Conclusion

While most students demonstrate a task-based approach to AI, using it for study support and academic efficiency, they often lack the critical awareness needed to fully evaluate its biases, economic structures, and broader societal implications. This gap underscores the need to integrate structured, reflective learning experiences into their curriculum.

The teaching sequence described in this text aims to foster the critical skills necessary to navigate the transformations of an AI-driven professional landscape. By incorporating critical role-play based on a case study into our LEA classes, we encourage students to move beyond a passive acceptance of AI-driven narratives and develop a deeper understanding of the ethical, technological, and ecological dimensions of these tools.

As AI continues to evolve, so too must our teaching approaches, ensuring that students become informed and critical participants in discussions on contemporary challenges such as AI and its societal impact.

___

NOTES

[1] MICROSOFT and LINKEDIN, Work Trend Index Annual Report, 2024. https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/worklab/work-trend-index (retrieved 20 May, 2025).

[2] Op. cit., p. 13

[3] Op. cit., p. 9

[4] Op. cit., p. 21

[5] Chunpeng ZHAI, Santoso WIBOWO and Lily D. LI, “The effects of over-reliance on AI dialogue systems on students’ cognitive abilities: a systematic review”, Smart Learning Environments, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-024-00316-7

[6] The Languages for Specialists of Other Disciplines (LANSOD or LANSAD in French) sector is one of the most significant providers of ESP classes at the tertiary level.

[7] Ron CARUCCI, “In the Age of AI, Critical Thinking Is More Needed Than Ever”, Forbes, 2024. https://www.forbes.com/sites/roncarucci/2024/02/06/in-the-age-of-ai-critical-thinking-is-more-needed-than-ever/ (retrieved 20 May, 2025).

[8] Wiwin DARWIN et al., “Critical Thinking in the AI Era: An Exploration of EFL Students’ Perceptions, Benefits, and Limitations”, Cogent Education, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2023.2290342

[9] Malik SALLAM, et al., “ChatGPT Applications in Medical, Dental, Pharmacy, and Public Health Education: A Descriptive Study Highlighting the Advantages and Limitations”, Narra Journal, 2023. https://doi.org/10.52225/narra.v3i1.103

[10] Michael BAMBERG and Molly ANDREWS, Considering Counter-Narratives: Narrating, Resisting, Making Sense, Amsterdam / Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing, 2004. https://doi.org/10.1075/sin.4

[11] James Paul GEE, An Introduction to Discourse Analysis: Theory and Method, London / New York: Routledge, 1999.

[12] Jean-François LYOTARD and Niels BRÜGGER, “What About the Postmodern? The Concept of the Postmodern in the Work of Lyotard”, Yale French Studies 99, 2001. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2903244 (retrieved 20 May, 2025).

[13] Carlos KÖLBL, Blame It on Psychology!?, in Michael BAMBERG and Molly ANDREWS, op. cit.., p. 28. https://doi.org/10.1075/sin.4.05kol

[14] James Paul GEE, An Introduction to Discourse Analysis: Theory and Method, London / New York: Routledge, 1999.

[15] MICROSOFT and LINKEDIN, Work Trend Index Annual Report, 2024. https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/worklab/work-trend-index (retrieved 20 May, 2025).

[16] Op. cit., p. 5

[17] Vanessa BOULLET, Amy D WELLS, Julien GUILLAUMOND and Sophie GONDOLLE, “Cartographie des jeux sérieux en LEA”, RILEA, 2024. https://anlea.org/categories_revue/revue-rilea-3-2024/ (retrieved 20 May, 2025).

[18] Paul NATION and John MACALISTER, Language Curriculum Design, New York: Routledge, 2019. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429203763

[19] Johann FISCHER, Case Studies in University Language Teaching and the CEF Levels, Helsinki, Finland: University of Helsinki Language Centre Publications, 2005.

[20] Rosalie LALANCETTE, L’étude de cas en tant que stratégie pédagogique aux études supérieures : recension critique, Québec, Canada : Livres en ligne du CRIRES, 2014. https://lel.crires.ulaval.ca/sites/lel/files/etude_de_cas_strategie.pdf (retrieved 20 May, 2025).

[21] Shawna SHAPIRO and Lisa LEOPOLD, “A Critical Role for Role-Playing Pedagogy”, TESL Canada Journal, 2012, p.121. https://doi.org/10.18806/tesl.v29i2.1104

[22] Op. cit., p.121

[23] Op. cit., p.121

[24] Rashid SUMAIRA and Shahzada QAISAR, Role Play: A Productive Teaching Strategy to Promote Critical Thinking, Bulletin of Education and Research, 2017. https://pu.edu.pk/images/journal/ier/PDF-FILES/15-39_2_17.pdf (retrieved 20 May, 2025).

[25] Shawna SHAPIRO and Lisa LEOPOLD, op.cit., p.123

[26] Ibid.

[27] Keshav JHA, CHATGPT HACKS FOR TEACHERS: A Comprehensive ChatGPT Guide for Educators for Teaching and Learning with Step-by-Step Instructions, Practical Demonstrations, Examples, Prompts, and Video Outputs, Maxlife Publishing, 2023.

[28] Shane SNIPES, Transforming Education with AI: Guide to Understanding and Using ChatGPT in the Classroom, PublishDrive, 2023.

[29] JHA and SNIPES, op. cit.

[30] Kate RAWORTH, “A Safe and Just Space for Humanity”, Oxfam Discussion Paper, 2012. https://www.oxfam.org/en/research/safe-and-just-space-humanity (retrieved 20 May, 2025).

[32] It is important to be able to restrict access to these platforms in order to protect student identities, in line with the European regulations on data protection.

___

Date de réception de l’article : 13 février 2025

Date d’acceptation de l’article : 30 mai 2025

Mise en ligne : 14 novembre 2025

Bibliographie

BAMBERG, Michael and Molly ANDREWS, eds., Considering Counter-Narratives: Narrating, Resisting, Making Sense. Amsterdam / Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing, 2004. https://doi.org/10.1075/sin.4

BOULLET, Vanessa, Amy D. WELLS, Julien GUILLAUMOND and Sophie GONDOLLE, eds., “Cartographie des jeux sérieux en LEA”, RILEA, Volume 3, 2024. Retrieved 20 May 2025, from https://anlea.org/categories_revue/revue-rilea-3-2024/

COUNCIL OF EUROPE, Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment – Companion Volume, Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing, 2020. Retrieved 20 May 2025, from https://www.coe.int/en/web/common-european-framework-reference-languages/

CARUCCI, Ron, “In the age of AI, critical thinking is more needed than ever,” Forbes, 2024. Retrieved 20 May 2025, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/roncarucci/2024/02/06/in-the-age-of-ai-critical-thinking-is-more-needed-than-ever/

DARWIN, Wiwin, Diyenti RUSDIN, Nur MUKMINATIEN, Nunung SURYATI, Ekaning D. LAKSMI, and Maros MARZUKI, “Critical Thinking in the AI Era: An Exploration of EFL Students’ Perceptions, Benefits, and Limitations”, Cogent Education, vol. 11 (1), 2024, pp. 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2023.2290342 .

FISCHER, Johann, Case Studies in University Language Teaching and the CEF Levels, Helsinki, Finland: University of Helsinki Language Centre Publications, 2005.

GEE, James Paul, An Introduction to Discourse Analysis: Theory and Method. London / New York: Routledge, 1999.

JHA, Keshav, CHATGPT HACKS FOR TEACHERS: A Comprehensive ChatGPT Guide for Educators for Teaching and Learning with Step-by-Step Instructions, Practical Demonstrations, Examples, Prompts, and Video Outputs. Maxlife Publishing, 2023.

LALANCETTE, Rosalie, L’étude de cas en tant que stratégie pédagogique aux études supérieures : recension critique, Québec, Canada : Livres en ligne du CRIRES, 2014. Retrieved 20 May, from https://lel.crires.ulaval.ca/sites/lel/files/etude_de_cas_strategie.pdf

LYOTARD, Jean-François and Niels BRÜGGER, “What about the Postmodern? The Concept of the Postmodern in the Work of Lyotard.” Yale French Studies 99 (Jean-François Lyotard: Time and Judgment), 2001, pp. 77-92. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2903244

MICROSOFT and LINKEDIN, Work Trend Index Annual Report. 2024. (n.d.). Retrieved 20 May 2025, from https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/worklab/work-trend-index

KÖLBL, Carlos, “Blame It on Psychology!?” In Michael BAMBERG & Molly ANDREWS eds., Considering Counter-Narratives: Narrating, Resisting, Making Sense, Amsterdam / Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing, 2004, pp. 27–32. https://doi.org/10.1075/sin.4.05kol

NATION, I. S. Paul and John MACALISTER, Language Curriculum Design, New York: Routledge, 2019. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429203763

RAWORTH, Kate, “A Safe and Just Space for Humanity”, Oxfam Discussion Paper, 2012, pp. 1-26. Retrieved 20 May, from https://www.oxfam.org/en/research/safe-and-just-space-humanity

SALLAM, Malik, Nesreen A. SALIM, Muna BARAKAT, and Alaa B. AL-TAMMEMI, “ChatGPT Applications in Medical, Dental, Pharmacy, and Public Health Education: A Descriptive Study Highlighting the Advantages and Limitations,” Narra Journal, vol. 3 (1), 2023, pp. 1 – 14. https://doi.org/10.52225/narra.v3i1.103

SHAPIRO, Shawna and Lisa LEOPOLD, “A Critical Role for Role-Playing Pedagogy,” TESL Canada Journal, vol. 29 (2), 2012, pp. 120-130. https://doi.org/10.18806/tesl.v29i2.1104

SNIPES, Shane, Transforming Education with AI: Guide to Understanding and Using ChatGPT in the Classroom (AI for Education Book 1). PublishDrive, 2023.

SUMAIRA, Rashid and Shahzada QAISAR, “Role Play: A Productive Teaching Strategy to Promote Critical Thinking,” Bulletin of Education and Research, vol. 39 (2), 2017, pp. 197-213. Retrieved 20 May, from https://pu.edu.pk/images/journal/ier/PDF-FILES/15-39_2_17.pdf

ZHAI, Chunpeng, Santoso WIBOWO, and Lily D. LI, “The effects of over-reliance on AI dialogue systems on students’ cognitive abilities: a systematic review”, Smart Learning Environments, vol. 11, 2024, pp. 1-37. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-024-00316-7

Auteurs

William KELLEHER

Université Rennes 2, LIDILE

william.kelleher @ univ-rennes2.fr

Evgueniya LYU

Université Grenoble Alpes, ILCEA4-GREMUTS

evgueniya.lyu @ univ-grenoble-alpes.fr

Lily SCHOFIELD

Université Rennes 2, LIDILE

Résumé

Abstract

In a teaching sequence based on a case study and critical role-play, we seek to raise Applied Foreign Languages undergraduate students’ awareness of the transitions and transformations brought by artificial intelligence. These transitions have societal, ethical, technological, and ecological dimensions. The sequence explores the economics, start-ups, and personalities of Silicon Valley in order to question uses, decision-making processes, and professional environments linked to AI.

Keywords: pedagogy, AI, critical role-play, critical discourse, multimodality, narrative, case study

Résumé

Dans une séquence pédagogique fondée sur une étude de cas et un jeu de rôle critique, nous cherchons à sensibiliser les étudiants et les étudiantes de licence en Langues Etrangères Appliquées aux transitions et transformations induites par l’intelligence artificielle. Ces transitions ont des dimensions sociétales, éthiques, technologiques et écologiques. La séquence explore l’économie, les start-ups et les personnalités de Silicon Valley afin d’interroger les usages, les processus de décision et les environnements professionnels liés à l’IA.

Mots-clés : pédagogie, IA, jeux de rôle critiques, approches critiques de discours, multimodalité, narrative, étude de cas

Texte

Introduction

With the rise of artificial intelligence (AI) tools, questions about their societal role and technological, ethical, and ecological implications are receiving increasing attention. As these tools become more prevalent across various professional sectors, concerns arise not only about their impact on the nature of work, but also on essential skills, such as decision-making, critical thinking, or creativity. For instance, according to the 2024 Work Trend Index Annual Report by Microsoft and LinkedIn[1], 71% of sector leaders state that they would prefer to, “hire a less experienced candidate with AI skills rather than a more experienced candidate without them”[2]. It is, therefore, crucial to encourage pedagogic reflection on how AI tools are now integrated into professional and pedagogic practices and on striking a balance between how they can facilitate complex tasks, and, “liberate workers from menial work and enable innovation and creativity to flourish”[3] whilst trying to avoid over-reliance. Such over-reliance can translate, in the workplace, as over delegation of editing and creative functions[4], or, at university, in adoption of practices[5] that are, essentially, plagiaristic.

This pedagogic testimony presents a teaching sequence designed for French undergraduate Applied Foreign Languages (LEA) students, that aims to assist in equipping these students to engage critically with AI technologies by bringing them into the class in order to examine their use, the key personalities and companies associated with them, and better understand their (dis)advantages. In the sections that follow, we begin, firstly, by outlining the theoretical and pedagogical foundations for our sequence, focusing on the role of counter-narratives and critical role-play case studies in the language classroom and in LEA/LANSAD[6] contexts. Secondly, we describe the implementation of our teaching sequence, structured around the technological, ethical, and ecological transformations associated with AI. Thirdly, we discuss questions of evaluation related to the sequence and to student productions, and some initial findings.

Critical pedagogies

One aspect of professional courses, like LEA/LANSAD, is the design of teaching and learning environments that enhance students’ critical thinking, among other soft skills, in order to make them as competitive as possible in today’s labour market. AI and its almost unlimited potential for multimodal generation and synthesis has dynamited discussions about critical thinking. Two distinct schools of thought are emerging: one emphasises the possible added value, particularly for businesses, in critically using generative AI, whereas the other notes its limitations and the dangers of uncritical over-reliance[7] [8] [9]. These camps are associated with different narratives of technological progress. The GAFAM (Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon, and Microsoft) or the ‘Magnificent Seven’ (Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta Platforms, Microsoft, NVIDIA, and Tesla) through communications, product releases, and market orientation, promote narratives that generally advocate for screen culture, and the objectification of knowledge and ontology. Against these ‘dominant’ narratives, counter-narratives circulate as, “stories which people tell and live which offer resistance, either implicitly or explicitly”[10].

Counter-narratives may be harnessed in pedagogy to both more beneficially and multidimensionally understand new technologies and offer resistance to potentially harmful or constrained ways of working, learning, and being a student. ‘Dominant’ cultural narratives are circulated by those in power. They are what Gee[11] refers to as ‘big D’ discourses, or what Lyotard and Brügger[12] define as ‘grand’ narratives. Kölbl[13] offers an interesting qualification of the term, noting that it may refer to, i) the version of a narrative that is most common, ii) a discourse or ideology that has become naturalised, iii) a narrative that is unequally distributed among divergent population groups, or iv) a particular way of talking that impacts on the structure and function of narratives.

There are, consequently, many ways in which people can resist dominant narratives: i) through composing alternate versions of a narrative – versions that advance distinctive plots and protagonists, ii) denaturalising discourses and ideologies and, on the contrary, drawing attention to the contradictions and ill-desired outcomes of these big D framings, iii) redrawing cultural and group-related boundaries and sharing narratives and, finally, iv) being aware of the language one draws on to tell a story. OpenAI itself can be used as an example. The dominant narrative of the company, voiced by Sam Altman, is that of a pioneer working to ensure that AI benefits all of humanity; a narrative frequently echoed in media and institutional discourse. This narrative has become so common that it conceals specific choices and values that shape the path taken. It can be denatured by identifying and deconstructing the techno-solutionist ideology, which highlights the importance of rapid AI development as essential to outpace potential threats, and its silence with respect to ecological issues. In addition, while AI is beneficial for developers, policymakers, or investors, it also disempowers precarious workers, educators, students, etc. These different groups can, similarly, be identified and aligned with. Finally, the very language used by OpenAI, that is full of technical abstraction, specialised jargon, conditional futurity, and utopian promise, structures its discourse in ways that delay critique. This language can be analysed for person deixis, connotation, and modality as one would do for simple critical discourse analysis (CDA)[14] and thereafter reframed or retold. These are, however, discursive and identificatory, rather than technological, insights, and it is very important to the design of our language course that the very tools of OpenAI, such as ChatGPT, can be used to engage with these narratives, critically understand them, and advance possible counter-narratives.

The objective of our pedagogical sequence is twofold: we seek both to enhance students’ critical thinking and creativity, and to raise their awareness of the advantages, dangers, and ethical, societal or environmental issues associated with AI. Our motivation lies in the idea that as educators, we have to prepare our students for their future professional paths, and whether we like it or not, society is undergoing significant transitions and transformations induced by various technological advances, in the AI sphere in particular. The report by Microsoft and LinkedIn[15], based on the answers of 31,000 people from 31 countries, reveals that 75% of workers use AI to save time, to focus on their most important work, to be more creative, in other words, “to not just work faster, but to work smarter”[16]. The report notes that AI is not necessarily replacing or eliminating jobs, but transforming existing ones and creating new ones.

In language-related jobs, like the ones our LEA students are most likely to have, such transformations are quite significant. LEA Students are wondering whether there is still a need to master foreign languages, whether jobs in translation are going to exist in the future, whether they chose the right bachelor’s programme, and whether the skills and knowledge they have acquired, and are still acquiring, are going to be relevant. Hence, it seems only logical to offer relevant and vocational courses to our students to make them aware of such transformations and, thus, begin the conversation on how to knowingly use AI tools. Integrating AI into our classes is a way for us, as language teachers, to discover our students’ AI-related practices and to moderate their fears or excessive enthusiasm, by guiding them through the advantages and limitations of such technologies.

Given the objectives of our teaching sequence, we choose to use role-plays and case studies, two teaching techniques that align with the literature on foreign/second language teaching and learning, including English and English for Specific Purposes (ESP)[17] [18]. These techniques also comply with the recommendations of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages to implement an action-oriented approach in foreign/second language education. Both role-plays and case studies are particularly appropriate for use in LEA/LANSAD teaching and represent an added value in such fields as they mimic real-life communication and close-to-authentic professional situations: i) they allow for group work and pair work, which introduces differentiation into the class and increases student output by promoting learning by doing, ii) they foster a less stressful environment for students who struggle with face-to-face interaction, iii) they tap into soft skills (time management, collaborative work, creativity, problem-solving, risk-taking, analytical and critical thinking) that are essential for students’ professional and personal development, and iv) they help develop students’ language and linguistic skills[19]. Given these advantages, it seems only logical to combine these two techniques and base a role-play on a case study.

Case studies have interesting pedagogical origins. In the early 20th century, Harvard Law School, followed closely by Harvard School of Business, began regularly integrating the case study approach. Since then, other universities and faculties have adopted it to teach diverse subjects, including social sciences, mathematics, chemistry, and foreign/second languages. Owing to its close ties to disciplines such as law, economics, management, etc., the approach appears especially appealing for teaching foreign languages in LEA/LANSAD departments. However, it is worth mentioning that its success largely depends on whether the selected case is both relevant and timely, whether the medium (paper vs online materials) is engaging, and whether the case structure (open vs closed) encourages students to rely solely on teacher-provided materials, or explore various other resources they deem necessary to solve the problems presented[20].

Role-plays have been widely used in humanities-focused disciplines, social sciences and hard sciences. Initially associated with, “the early days of the communicative approach”[21] to teach foreign/second languages, they received strong criticism in the 1990s, after which their use declined significantly[22]. The concept of role-play encompasses a variety of teaching possibilities. As Shapiro and Leopold[23] point out, they involve, “some kind of role and some sort of play.” They can be applied at different educational levels (elementary and secondary schools, tertiary institutions, lifelong language learning courses[24]) and for various pedagogical purposes (e.g., to develop receptive or productive language skills, to enhance linguistic competence, to build soft skills, and to familiarise learners with specific contents, etc.). Hence, when designing role-plays, practitioners should strive to engage learners in a way that guarantees, “cognitive challenge while still creating the conditions for improved linguistic competence”[25]. The adjective “critical,” placed before “role-play,” refers to the idea that the latter preferably aims to allow students to, “embody voices and perspectives that may be quite different from their own” [26] or from the mainstream (i.e., dominant, naturalised, big D).

Role-plays and case studies have recently faced criticism due to concerns that students might be tempted to delegate some tasks to AI tools, especially given that these tools tend to perform better when prompts specify a role for the AI to assume[27] [28]. However, AI’s good performance does not deprive such teaching approaches of their relevance. When properly designed, they can actually offer an opportunity to reflect on the added value of human intelligence and, in contradistinction, the temptation to outsource analytic work, questions of intellectual property, plagiarism, authorship, and integrity. In our teaching sequence, we invite students to carry out most of these tasks in the classroom, under teacher supervision, which encourages students to use AI responsibly and reflectively. Moreover, these two approaches are beneficial not only for students, but also for instructors. AI tools have a latent transformative pedagogic potential, in helping teachers conceive scenarios for role-plays and case studies where the accent is on student creativity, critical thinking, and ethical awareness[29].

Taking into consideration the aforementioned elements, we have decided to design our role-play around the highly debated topic of AI by exploring alternative narratives about its use. We aim to challenge the narratives that are commonly circulated in professional circles, and thereby foster students’ critical awareness of AI-mediated language, both professionally and educationally. We use critical role-play in the context of a case study focused on key figures and enterprises in Silicon Valley. Our teaching materials guide students through an exploration of Sam Altman’s ethics and the reasons for his initial dismissal from OpenAI, while also encouraging broader reflection on current discourses surrounding AI, such as those embodied by Elon Musk or Alphabet, so that students learn to question and critically assess them.

The teaching sequence

The teaching sequence is designed to cover half a semester, with pre- and post-sequence activities. It is intended for third-year LEA students who are expected to have achieved a B2–C1 level of the CEFR. There is a strong emphasis, in the sequence, on multimodality and computer-assisted reading and writing. The lexical elements that we wish to emphasise are those concerned with identity and personal style, the stock market and economic environment, and, crucially, the sector of AI and audit. In our critical role-play scenario, students take on specific roles within a fictive specialised task force at Alphabet Inc., whose aim is to protect the company’s position in the competitive AI landscape. This is done by leading a multifaceted investigation and assessment of the risks and benefits associated with AI, by considering recent controversies, ethical issues, and economic threats and opportunities. As members of this task force, students contribute to developing a plan for Alphabet’s future in the field (Fig. 1) which naturally touches on technological, ethical, and ecological considerations.

Fig. 1 – Instructions for the role-play and group creation phase

Session 1 of the sequence establishes a base-line in terms of students’ knowledge of AI tools and their knowledge of key personalities and enterprises of Silicon Valley. It is accompanied by an online questionnaire, consisting of ten open-ended items, that seeks to quantify data on student appreciations and attitudes:

- When you hear ‘AI’ what comes to mind?

- How many AI tools have you tried?

- Which AI tools have you tried?

- Do you use AI tools? If so, which ones?

- Explain the steps you would have to undertake if using an AI tool to revise/write a text.

- When do you use them? Why?

- What do you like about using AI tools?

- What do you dislike about using AI tools?

- Do you think AI tools perform better or worse than humans?

- Do you think it’s right to use AI, and why?

Session 2 makes use of an AI-generated video to introduce group work in a meaningful way and assigns group roles (business development manager, policy advisor, etc.) based on research into real-world corporate structure. The reasons for generating the introductory video with the help of AI are to diversify the modality of teaching materials and task instructions, typically presented in written form, and to simulate a real-life situation with tailor-made information. This reinforces the emphasis on role-playing. The session also requires students to film and share their research into the risks and benefits of AI – it is a first task on the theme that is deepened in subsequent sessions.

Session 3 delves into the biographies of key personalities of Silicon Valley (Brockman, Pichai, Page, Nadella, Musk, Zatlyn), and draws a (Myers Briggs) psychological profile based on research and a class debate.

This session also looks into how Large Language Models (LLMs) have pre-established filters and hidden ideological coordinates, by requiring students to critically compare texts generated by two or more different LLMs in response to prompts about Sam Altman, thus reflecting on these platforms’ impartiality or lack thereof (Fig. 2). Students again film and share their research, taking on different group roles, with the aim of creating close-to-authentic professional situations and mimicking real-life communication.

Fig. 2 – Instructions for the LLM responses’ comparison activity

Session 4 uses Open AI as a case study in order to explore start-up market capitalisation. This leads to questions of share price and market fluctuation. Shareholder demands are compared to the text by Kate Raworth on the ‘doughnut’ of safe and just development[30].

Session 5 begins the task of preparing the group submission to the class that may include video or AI-generated multimodal texts. The brief aims to move from students’ knowledge of the sector to an informed appraisal of policy (Fig. 3).

Session 6 provides an opportunity for the groups to present their reports.

As mentioned previously, using AI tools is not forbidden in task instructions, given that one of the teaching sequence’s aims is to guide students to consider the transformations to tasks brought about by AI. Following the sequence, there is a questionnaire that aims to measure the increase in student awareness of AI-related issues and any resulting change in appreciations and attitudes.

Fig. 3 – Instructions for the final role-play report

From the above summary of the teaching sequence, one can appreciate three separate, but complementary, axes: technological, ethical, and developmental/ecological. The technological axis concerns knowledge of LLMs, their different uses and biases, and research into Silicon Valley’s corporate and economic functioning. The ethical aspect concerns the bases for the decisions made by key personalities in the AI sector, the increasing power of tech giants over our lives and intimacies, and the ethics of use of AI tools. Finally, the developmental/ecological aspect covers the capitalisation of these kinds of startups, but also the environmental impact of the LLM value chain, with an emphasis on the energy implications of blockchain technologies. This last axis extends to Altman’s other projects, such as his WorldCoin cryptocurrency, or recent start up with Jony Ive, the designer of the iPhone. In inquiring into these questions, students can rely on a huge amount of both scientific and journalistic sources that span the period from ChatGPT’s unveiling to recent incognitos and suspicions.

Questions of evaluation and some initial findings

To evaluate the sequence in pedagogical terms, we have designed a multi-layered approach that includes pre- and post-questionnaires, three in-sequence evaluations, and class observation. The pre-questionnaire consists of ten open-ended items, discussed above, whose goal is to gather information on students’ awareness of the AI sector. The post-questionnaire contains the same ten open-ended items, rephrased, and five Likert-scale items to assess students’ perceptions of the sequence in terms of both knowledge/competence acquisition and motivation. Comparing students’ responses to the open-ended items in the pre- and post-questionnaires offers insights into whether and how the sequence has influenced their awareness of AI. Student motivation may also be evaluated through class observations.

These measures are completed by in-sequence assessment of oral and written output. Students record videos (to be posted on Padlet or open access alternatives like Digipad[31] [32]): in the first one, they outline the risks and benefits of AI, and in the second one, they share their conclusions concerning the answers provided by ChatGPT and one other LLM to a prompt asking to describe Sam Altman. For the third in-sequence evaluation, students produce either a written or a video report proposing a strategic roadmap for Alphabet Inc. to navigate current AI controversies and remain competitive in a rapidly evolving tech landscape (Fig. 3). This is particularly pertinent in a post-Deepseek, post-Trump, environment that was able to knock a third off Nvidia’s share value in a weekend. Students’ video tasks and their final report are to be evaluated from several angles: critical and analytical thinking, acquisition of specialised AI-related knowledge, including linguistic means, like AI- and technology-related terminology, employed to engage with or convey it, as well as creativity in proposed solutions and reflections, such as stylistic features, irony, metaphors, figurative language, word coinage, and creative technological solutions to make videos.

Preliminary pedagogical findings would suggest that students have a task-based approach to AI, using it to condense readings, isolate arguments and analyse data, or even to create quizzes based on their course notes and thus facilitate learning in preparation for class tests or presentations. This is not to overlook less appropriate uses of AI, such as delegating the writing of assignments. They have already incorporated AI into their study habits and LLMs are, de facto, an integral part of the university’s academic ecology. Additionally, students have a generally positive attitude towards AI and recognise the strengths of LLMs in comparison to other, previous, knowledge distribution systems, such as Wikipedia or browser searches.

However, findings seem more mitigated when it comes to critical appraisal of the results that LLMs generate. Students seem to lack the personal general knowledge (historical dates, places, authors, concepts) that would allow them to accurately appraise the reliability of a return. They also seem to not understand the business model that is behind big tech generally and LLMs in particular. Their use of AI is, as a result, a curious mixture of worldliness and naiveté. They, for instance, do understand the economics behind paywalls, and accuse LLMs of being, “more stupid now than they used to be” in reference to OpenAI requiring more prompts of free users than they do of pro users. However, larger questions of knowledge economies and the benefits that can accrue to companies that control information seem not to have occurred to them before the sequence. There is, as a result, space, and need, for a teaching sequence such as this in their university curricula.

In-sequence assessment supports other preliminary findings. Student video tasks are creative in the chosen format (e.g., journalistic interview; testimonial type documentary) and in video editing choices (e.g., appropriate background music, hidden faces for anonymity). While some groups are motivated by their Alphabet Inc. roles as provided within the role-play (legal expert, education expert, business development manager, investor), and are keen to adopt them as part of the risks and benefits video, others add different yet relevant roles to illustrate their arguments and create contrast. These may be, for example, i) a radiologist to testify on the benefits of AI in the medical field vs. a translator who exposes the risks and dangers for the profession, or ii) a successful and rich individual who made their fortune through AI vs. a victim of financial fraud through the use of deepfake. The portrayals of these roles are complemented with details that allow them to contrast AI’s roles in different parts of the world (e.g., India and the United States). Setting up and encouraging fictional yet realistic professional roles from the outset seems to allow students to take a step back from the narratives, which circulate in their sphere, and put forward more critical statements on AI’s societal role. The details they add (professional and geographical coordinates) show a budding awareness of more specific facets of AI according to the aforementioned technological, ethical, and ecological dimensions.

Conclusion

While most students demonstrate a task-based approach to AI, using it for study support and academic efficiency, they often lack the critical awareness needed to fully evaluate its biases, economic structures, and broader societal implications. This gap underscores the need to integrate structured, reflective learning experiences into their curriculum.

The teaching sequence described in this text aims to foster the critical skills necessary to navigate the transformations of an AI-driven professional landscape. By incorporating critical role-play based on a case study into our LEA classes, we encourage students to move beyond a passive acceptance of AI-driven narratives and develop a deeper understanding of the ethical, technological, and ecological dimensions of these tools.

As AI continues to evolve, so too must our teaching approaches, ensuring that students become informed and critical participants in discussions on contemporary challenges such as AI and its societal impact.

___

NOTES

[1] MICROSOFT and LINKEDIN, Work Trend Index Annual Report, 2024, [https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/worklab/work-trend-index].

[2] Op. cit., p. 13.

[3] Op. cit., p. 9.

[4] Op. cit., p. 21.

[5] Chunpeng ZHAI, Santoso WIBOWO and Lily D. LI, “The effects of over-reliance on AI dialogue systems on students’ cognitive abilities: a systematic review”, Smart Learning Environments, 2024, [https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-024-00316-7].

[6] The Languages for Specialists of Other Disciplines (LANSOD or LANSAD in French) sector is one of the most significant providers of ESP classes at the tertiary level.

[7] Ron CARUCCI, “In the Age of AI, Critical Thinking Is More Needed Than Ever”, Forbes, 2024, [https://www.forbes.com/sites/roncarucci/2024/02/06/in-the-age-of-ai-critical-thinking-is-more-needed-than-ever/].

[8] Wiwin DARWIN et al., “Critical Thinking in the AI Era: An Exploration of EFL Students’ Perceptions, Benefits, and Limitations”, Cogent Education, 2024, [https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2023.2290342].

[9] Malik SALLAM, et al., “ChatGPT Applications in Medical, Dental, Pharmacy, and Public Health Education: A Descriptive Study Highlighting the Advantages and Limitations”, Narra Journal, 2023, [https://doi.org/10.52225/narra.v3i1.103].

[10] Michael BAMBERG and Molly ANDREWS, Considering Counter-Narratives: Narrating, Resisting, Making Sense, Amsterdam / Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing, 2004, [https://doi.org/10.1075/sin.4].

[11] James Paul GEE, An Introduction to Discourse Analysis: Theory and Method, London / New York: Routledge, 1999.

[12] Jean-François LYOTARD and Niels BRÜGGER, “What About the Postmodern? The Concept of the Postmodern in the Work of Lyotard”, Yale French Studies 99, 2001, [https://www.jstor.org/stable/2903244].

[13] Carlos KÖLBL, Blame It on Psychology!?, in Michael BAMBERG and Molly ANDREWS, op. cit.., p. 28. [https://doi.org/10.1075/sin.4.05kol].

[14] James Paul GEE, An Introduction to Discourse Analysis: Theory and Method, London / New York: Routledge, 1999.

[15] MICROSOFT and LINKEDIN, Work Trend Index Annual Report, 2024, [https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/worklab/work-trend-index].

[16] Ibid., p. 5.

[17] Vanessa BOULLET et al., “Cartographie des jeux sérieux en LEA”, RILEA #3, 2024, [https://anlea.org/categories_revue/revue-rilea-3-2024/].

[18] Paul NATION and John MACALISTER, Language Curriculum Design, New York: Routledge, 2019, [https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429203763].

[19] Johann FISCHER, Case Studies in University Language Teaching and the CEF Levels, Helsinki, Finland: University of Helsinki Language Centre Publications, 2005.

[20] Rosalie LALANCETTE, L’étude de cas en tant que stratégie pédagogique aux études supérieures : recension critique, Québec, Canada : Livres en ligne du CRIRES, 2014, [https://lel.crires.ulaval.ca/sites/lel/files/etude_de_cas_strategie.pdf].

[21] Shawna SHAPIRO and Lisa LEOPOLD, “A Critical Role for Role-Playing Pedagogy”, TESL Canada Journal, 2012, p.121, [https://doi.org/10.18806/tesl.v29i2.1104].

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Rashid SUMAIRA and Shahzada QAISAR, Role Play: A Productive Teaching Strategy to Promote Critical Thinking, Bulletin of Education and Research, 2017, [https://pu.edu.pk/images/journal/ier/PDF-FILES/15-39_2_17.pdf].

[25] Shawna SHAPIRO and Lisa LEOPOLD, op. cit., p.123.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Keshav JHA, CHATGPT HACKS FOR TEACHERS: A Comprehensive ChatGPT Guide for Educators for Teaching and Learning with Step-by-Step Instructions, Practical Demonstrations, Examples, Prompts, and Video Outputs, Maxlife Publishing, 2023.

[28] Shane SNIPES, Transforming Education with AI: Guide to Understanding and Using ChatGPT in the Classroom, PublishDrive, 2023.

[29] JHA and SNIPES, op. cit.

[30] Kate RAWORTH, “A Safe and Just Space for Humanity”, Oxfam Discussion Paper, 2012, [https://www.oxfam.org/en/research/safe-and-just-space-humanity].

[32] It is important to be able to restrict access to these platforms in order to protect student identities, in line with the European regulations on data protection.

Auteurs

William KELLEHER

Université Rennes 2, LIDILE

Numéro Orcid: 0000-0001-8368-6404

william.kelleher@univ-rennes2.fr

Evgueniya LYU

Université Grenoble Alpes, ILCEA4-GREMUTS

Numéro Orcid: 0009-0007-4457-7038

evgueniya.lyu@univ-grenoble-alpes.fr

Lily SCHOFIELD

Université Rennes 2, LIDILE

Numéro Orcid: 0000-0002-2158-3116

lily.schofield@univ-rennes2.fr

Références

Pour citer cet article :

Evgueniya LYU, Lily SCHOFIELD, William KELLEHER - "William KELLEHER, Evgueniya LYU, Lily SCHOFIELD, Counter Narratives of Artificial Intelligence: Critical Role-Playing Pedagogies in an Applied Foreign Languages Classroom" RILEA | 2025, mis en ligne le 07/12/2025. URL : https://anlea.org/revues_rilea/william-kelleher-evgueniya-lyu-lily-schofield-counter-narratives-of-artificial-intelligence-critical-role-playing-pedagogies-in-an-applied-foreign-languages-classroom/