Résumé

Abstract

The shortfall in staff in the public health sector has become an increasing area of concern in recent years in the UK. The British Medical Association (BMA) reported that there were 124 000 unfilled vacancies in secondary care in June 2022 in England. The loss of EU staff following Brexit and new requirements for workers from EU countries have pushed NHS trusts to recruit overseas. Currently 34% of NHS doctors come from outside the UK, with a steady increase each year since the UK left the European Union. However, concerns exist over the viability of this recruitment in the long term and the impact on both the health system in Britain but also overseas, especially for those recruited from low income countries. Relying on foreign nationals to ensure the steady supply of health care workers comes with significant risks in terms of the stability of supply for the receiving country (which depends on the training and availability of skilled workers, ever changing regulations in relation to visas, etc.), but also for the source country (shortage of workers and/or disinvestment in local health systems. This article examines the complexities of international mobilisation of health workers using Global Political Economy (GPE) literature, other secondary analysis, empirical studies and grey literature. It includes a case study of the supply of health workers to the National Health Service (NHS) in the UK from India. While the case study is specific to the UK, it raises universal questions about recent trends in mobilisation of international health care workers and the impact on supply and demand in host and destination countries.

Keywords: GPE literature, NHS staff shortages, migration, India, UK

Résumé

La pénurie de personnel dans le secteur de la santé publique est devenue une préoccupation croissante ces dernières années au Royaume-Uni. L’Association médicale britannique (BMA) a signalé qu’il y avait 124 000 postes vacants dans les soins secondaires en juin 2022 en Angleterre. La perte de personnel européen à la suite du Brexit et les nouvelles exigences imposées aux travailleurs des pays de l’UE ont poussé les organisations des hopitaux du NHS (système national de santé) à recruter à l’étranger. Actuellement, 34 % des médecins du NHS viennent de l’extérieur du Royaume-Uni, avec une augmentation constante chaque année depuis que le Royaume-Uni a quitté l’Union européenne. Cependant, des inquiétudes subsistent quant à la viabilité de ce recrutement à long terme et à son impact sur le système de santé britannique, mais aussi à l’étranger, en particulier pour les personnes recrutées dans les pays en développement à faible revenu. Le fait de compter sur des ressortissants étrangers pour garantir un approvisionnement régulier en personnel de santé comporte des risques importants en termes de stabilité de l’offre pour le pays d’accueil (qui dépend de la formation et de la disponibilité de travailleurs qualifiés, de l’évolution constante de la réglementation en matière de visas, etc.), mais aussi pour le pays d’origine (pénurie de main-d’œuvre et/ou désinvestissement dans les systèmes de santé locaux). Cet article examine les complexités de la mobilisation internationale des professionnels de santé à l’aide de la littérature sur l’économie politique mondiale (EPM), d’autres analyses secondaires, d’études empiriques et de littérature grise. Il comprend une étude de cas sur l’approvisionnement en professionnels de santé du National Health Service (NHS) au Royaume-Uni en provenance d’Inde. Bien que cette étude de cas soit spécifique au Royaume-Uni, elle soulève des questions universelles.

Mots-clés: Recherche EPM, deficit des travailleurs du NHS, migration, Inde, Royaume-Uni

Texte

Introduction

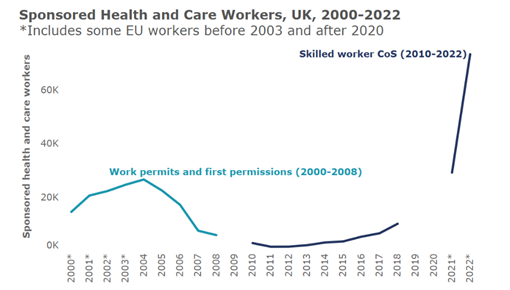

The National Health Service (NHS) in the four nations of the UK has become increasingly reliant on international staff. The loss of EU staff following Brexit and new requirements for workers from EU countries have pushed NHS trusts to recruit overseas. According to the Kings Fund, the international work force makes up 1 in 5 of all workers in the health service. Currently 37% of NHS doctors come from outside the UK, with a steady increase each year since the UK left the European Union[1]. The increase in staff recruitment from overseas of both NHS but also social care workers has been unprecedented as we can see from the table below with a significant upsurge in workers.

Graph 1 – Sponsored Health and Care Workers, UK, 2000-2022

Source: The Migration Observatory 2023

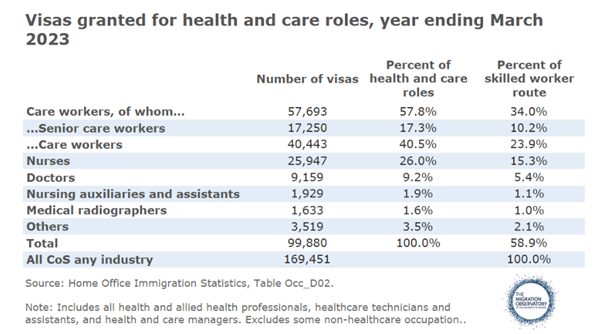

There has been notably an increase in visas for care workers since 2022 and recruitment of nurses and doctors from overseas have also continued to increase at a significant rate as we can see from the table below[2].

Graph 2 – Visas granted for health and care roles, year ending March 2023

Source: The Migration Observatory 2023

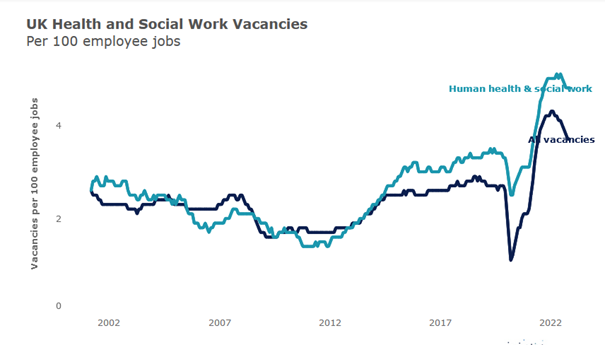

This surge in international recruitment in both health and social care can be explained by the shortfall in staff in the public health sector, which has become an increasing area of concern in recent years in the UK. The British Medical Association (BMA) reported that there were 124 000 unfilled vacancies in secondary care in June 2022 in England[3].

Graph 3 – UK Health and Social Work Vacancies

Source: The Migration Observatory 2023

International recruitment is thus a major solution for the UK to try and fill the significant vacancies. However, concerns exist over the viability of this recruitment in the long term and the impact on both the health system in the UK but also overseas, especially for those recruited from low income countries. Keir Starmer’s current government unveiled plans to cut international recruitment (overseas trained nurses and doctors) from 34% to 10% of the NHS workforce, so the current situation may change in the future, but for now international staff are a vital part of the NHS workforce[4]. The UK is not however unique regarding its reliance on international health staff. The OECD report Recent Trends in International Migration of Doctors, Nurses and Medical Students noted a significant increase in doctors, nurses and medical students across OECD countries. In the 18 OECD countries for which there was available data, the rate of both foreign-trained doctors increased by over 50% and the number of foreign-trained nurses by over 20% between 2010/11 and 2015/16[5].

Drawing on Global Political Economy (GPE) literature, empirical studies, government reports and grey literature, this paper considers the nexus between the cross-national supply of labour and the impact on health systems in home and destination countries. It also includes a case study on the specific case of Indian health care workers moving to the UK to increase the supply of health care workers in this country in order to illustrate the significant issues arising from transnational labour policies.

Mobilisation of health workers: Insights from GPE literature

Global Political Economy (GPE) studies are insightful to understand the impact on transnational movements of migrant workers on home and destination public health systems. GPE studies, which will be analysed in relation to migration of workers below, acknowledge that the global economy impacts significantly across the economy and societies including the the realms of politics, the economy, civil society and culture. GPE studies thus analyse the world economy to consider not only economic growth, poverty, and inequality, but also many social and economic factors regarding global industries, environmental sustainability, labour market impacts and more generally impacts on democratic governance. These studies take a multidisciplinary approach, drawing on various disciplines which analyse geographies and societal impacts. So this field of study, close to International Political Economy (IPE)[6], analyses the interaction between political and economic forces in the global economy and goes further than IPE by questioning its impact on human welfare. Global is preferred to International (IPE) because the literature considers the wider impact beyond relations between states. Walton Roberts takes a GPE approach and also draws on Health Human Resource literature (HHR)[7]. She posits that the globalisation of health care has accentuated the issue of a divide between the core and the periphery. The benefits have accrued to developed countries in the North which have benefited from the advancement of their healthcare systems[8]. Indeed, developed countries suffering from staff shortages have reached out to overseas expertise to fill these shortages. This is the case for example in the UK with the NHS, which has recruited migrant nurses and doctors since its inception to make up a shortfall. A fundamental way in which healthcare has been restructured is through training, contributing to the globalisation of health care, which has evolved towards a neoliberal or market-orientated form of health care delivery. Walton Roberts[9] argues that health education systems in the Global South[10] have been shaped to respond to international HHR circuits. Using Powell et al.’s analysis she thus contends that training is shaped by international goals and standards so that workers can compete in a global market[11]. This also confirms the findings of post-colonial studies which have examined how medical training has been influenced by colonial practices with, for example, Christian missionaries promoting international training[12]. Raghuram shows how the NHS has reaped the gains from the arrival of foreign migrant health professionals from former colonies which can be linked back to colonial practices[13]. Valiani criticises the export of migrant nurses from the Global South to service labour markets located in the Global North using the example of the Philippines whose educational system has been structured towards the demands of the US market following decolonisation[14]. In Walton Robert’s analysis of India, the author illustrates the process of global health training with the example of Manipal Education and Medical Group (MEMG), which is India’s third largest health care group with a significant network of hospitals[15]. This hospital is considered a top educational institution, heavily financed by US companies such as the International Finance Company (IFC) with strong emphasis on developing skills for the international market. IFC is a member of the World Bank Group and is considered to be the largest development institution working in the private sector in emerging economies.

Beyond international training, which has encouraged workers in the Global South to move to high-income countries, much of the literature focuses on more general push and pull factors. In the late 1800s, Ravenstein was one of the first authors to theorise on the push and pull factors for migration flows followed by Lee in 1966[16]. These push factors are important in order to explain the factors that may motivate workers to emigrate (push) and attract migrants to the country of destination (pull). Alonso-Garbayo and Maben’s study is interesting because it nuances the push/pull factors by drawing on an empirical study which examined the motivations of nurses migrating to the UK from India and Philippines[17]. The research was based on a study in one hospital trust based in London. The study however was fairly small: 6 participants from India and 15 participants from the Philippines. However, it confirmed much of the previous literature on the principal motivations to migrate which include employment, salary, holiday entitlement, pension and improvements to quality of life. Another important factor was the presence of family support in the country of destination. Other major predictors included professional development, whether there were opportunities for continued education and development and general career progression. For recently qualified nurses, migration was seen as a chance to further skills and knowledge, and senior nurses found that they had greater chances of development in a professional career in the UK. A major pull factor was also the availability of better technology, clinical resources and improved management. Professional autonomy was equally a very important pull factor, especially for those who had worked in the public sector in their home country where autonomy had been more limited, that is the ability to make decisions or take control of aspects of their jobs[18]. In addition to these incentives we can add issues of regulations and migration and labour policies which we will develop further in subsequent sections of the paper in relation to the UK’s recent policies. Suffice is to say that it was found to be relatively easier to obtain work in the UK: tests, requirements, and years of experience to qualify were less stringent than requirements in the US for example. The major push factors in the literature were conflict, political instability and insecurity in the home country. Old colonial ties were also found to be important in the migration to a specific country[19]. Arango, in another study, confirms the importance of historical ties, as well as cultural, economic and social factors in decisions of outmigration from the Global South to the Global North which go beyond the classic push and pull factors identified in the literature[20].

The impacts of transnational labour policies on the source country

As well as examining the push and pull factors, it is also important to consider the impact on both home and host countries of transnational labour policies which draw migrant workers to the Global North. The result of international mobilisation of health workers can be a brain drain. The negative impacts can be considered to be both direct and indirect and started to be reported from the 1990s onwards, with the increase of migration from the global North to the global South[21]. The most direct consequences of this outward flow of high-skilled medical professionals are skill shortages and fiscal costs because of educational subsidies which have been provided by the source country and then lost to the destination country. The negative effects on home systems also impact those who stay behind because of extra workloads, stress because of lack of staff and so forth[22]. Those who remain may also lose motivation for a number of reasons including comparatively lower pay, outdated equipment, less or unsatisfactory supervision and fewer career opportunities[23]. A loss of investment in education, training and human resource shortages have indeed been reported in a number of studies[24]. It has also been noted that migration of health workers can have a negative impact on healthcare education in the source country by depriving nations concerned of valuable educators and trainers to train future generations of healthcare workers. This can thus have a significant impact on the future supply of health care professionals and an overall negative impact on source country health care systems[25]. Stilwell also underlines the profound effects the loss of skilled healthcare workers can have on local communities. Developing countries depend on local health workers who are knowledgeable on the specific and often complex health needs of local communities[26]. Moreover, since the health workers who are able to secure jobs abroad are usually some of the most skilled workers, not only does it add to the brain drain but it may also result in the loss of political influence. Indeed, these highly proficient workers are often those who have the most political weight to push for health policy improvements and reforms[27]. The impact is thus considered to be wider than the health sector itself given the repercussions on education, research but also technology and other economic and social sectors. Indeed, given the links between health care delivery to alleviate social inequalities and the social determinants of health, social structures, whole economic, social and political structures are impacted by the outward flow of skilled health care workers[28].

Nevertheless, some positive aspects of the mobilisation of health workers at an international level have been observed; what proponents have called “brain circulation”. Health care professionals may make the most of the global health care market and use opportunities abroad to build up skills thanks to international training and professional experience. These professionals are then seen as a means of enhancing international expertise and training in their home country and thus improve health care in the home country (if and when they return)[29]. Moreover, Stillwell et al.[30] note that source countries can also benefit from remittances with expatriates sending money back and adding to the home country balance of payments. .

In order to assess the real impact of mobility of health workers and/or professional migration on health systems, in both source and receiving country, it is important to establish whether the migration is permanent or temporary. But, as Stillwell et al.[31] note, the actual definition of temporary is unclear and the nomenclature is not used with any consistency at an international level: classifications have varied from 9 months to 10 years[32]. Consistent and regular impact assessments are not carried out and data is scarce and often inconsistent[33]. Even when data exists on migration, it is impossible to follow every trajectory consistently and know whether health professionals have moved on a temporary or permanent basis and the actual impact this has had[34]. While most countries have specific requirements for entry and length of stay, national laws on residence and visa requirements are constantly changing, especially in the UK.

Case study of migration supplies of labour from India to the UK

UK policies resulting in an increase in Indian health professionals working in the UK post Brexit

The Indian government does not actively encourage but promotes out-migration. In line with the literature on the subject, Indian professionals and nurses in particular are lured by opportunities overseas because of the poor status of nursing in their home country (low pay, difficult working conditions, low staff to patient ratios, physical and verbal abuse)[35]. A private nursing recruiter in Chandigarh, India, reported in a series of interviews carried out by Walton Robert that while training may begin in India, often the practitioner will specialise, go overseas for experience and perhaps return to India later but will probably work in the private sector. Most private practices in India are interested in taking on health professionals who have international experience[36].

India is a very important source of health professionals for the UK. There has been a long history of collaboration in order for the UK to fill vacancies. Although the NHS is not the only sector, it is one of the most significant areas where recruitment takes place. The UK has traditionally recruited permanent and temporary workers from overseas to cope with staff shortages[37]. In order to alleviate pressure post Brexit, the UK made changes to its visa entry requirements for health care workers from abroad. In August 2020, the introduction of a new health and care worker visa facilitated the entry of medical professionals to the UK in order to address the lack of supply in public health and social care. In order to qualify for such a visa, applicants had to already have qualified as doctors, nurses, health professionals or care professionals and have obtained a firm job offer. This then had to be approved by the UK Home Office and qualifications needed a stamp of approval from the UK Certified authority Ecctis. Visas were then issued for five years with the possibility to request an extension and/or make an application for permanent settlement. The relaxing of entry for health and care was very important and led to a significant rise in the number of workers in that category. While this led to an inflow of immigrants from different destinations, those from India represented the biggest number for the particular visa category. The biggest rise was noted in the period 2022-2024, with an increase from 24 348 in June 2022 to 45, 943 in 2024[38]. However, recent legislation brought in in 2024 may lead to restricting the flow of inward health care workers again. In addition to more stringent conditions to come to the UK, it is no longer possible to bring dependants which will have an impact on the supply in the future.[39]

Brain drain and impact on the home health care system

As we have noted from the literature, one of the biggest concerns for the migration of Indians to the UK is the resulting brain drain. This has been a concern of both national and international bodies ever since the late 1990s when the effects were starting to be noticed on health systems in the Global South. In the UK, the Department of Health established ethical guidelines for recruiting nurses form overseas in 1999 which curbed some of the abusive regimes in recruitment[40]. In 2001, to shore up ethics in international recruitment, a Code of Practice henceforth governed the recruitment of overseas nurses. One of the main aims of this Code of Practice was to protect health systems in developing countries from brain drain. This was reinforced in 2004 with the drafting of a list of developing countries from which recruitment should be avoided because of the potential impact on their health care systems through lack of staff. Based on these Codes, the 2025 update has etablished the following guiding principles:

Best practice benchmarks

- There is no active recruitment of health and social care personnel from countries on the red country list.

- International recruitment will follow good recruitment practice and demonstrate a sound ethical approach.

- International health and social care personnel will not be charged fees for recruitment services in relation to gaining employment in the UK.

- International health and social care personnel will have the appropriate level of English language to enable them to undertake their role effectively and to meet registration requirements of the appropriate regulatory body.

- Appointed international health and social care personnel must be registered with the appropriate UK regulatory body.

- International health and social care personnel required to undertake supervised practice by a regulatory body should be fully supported in this process.

- International health and social care personnel will undergo the normal occupational health assessment before employment.

- All international health and social care personnel will have appropriate pre-employment checks including those for any criminal convictions or cautions as required by UK legislation.

- International health and social care personnel offered a post will have a valid visa before entry to the UK.

- Appropriate information about the post being applied for will be made available so candidates can make informed decisions.

- Recruiters, contracting bodies and employers must observe fair and just contractual practices.

- Repayment clause included in an employment contract must abide by the 4 principles of transparency, proportionate costs, timing and flexibility.

- Newly appointed employees will be offered appropriate support and induction. Employers and contracting bodies should undertake pre-employment and placement preparation to ensure a respectful working environment.

- Employers and recruitment organisations should respond appropriately to applications from international health and social care personnel who are making a direct application.

- International recruitment activities should be recorded to support the monitoring and measurement of international workforce flows and their impact. »[41]

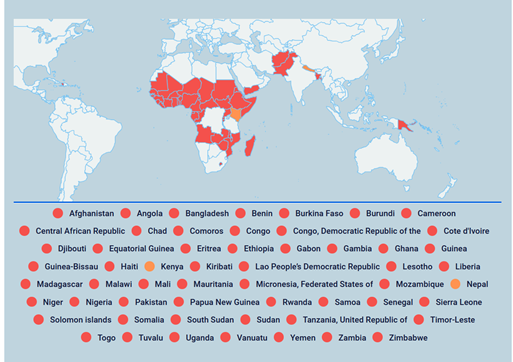

The Commonwealth Code of Practice also reinforced the norms for the international recruitment of health workers to ensure that international recruitment was banned from those countries already suffering from shortages back home. This Code of Practice was signed by the UK and India. They also signed the WHO Code of Practice which agrees to adhere to blocking international recruitment from red list countries: those countries which would be seen as compromising health systems at home if they were to allow recruitment abroad. Below is the most updated version of the red list:

Image 1 – Red List of the WHO Code of Practice

Source: NHS EMPLOYERS, 2025

However, since India is not on the red list of countries because they train sufficient health professionals, it fails to protect India from a brain drain. In addition, the Code of Practice does not apply to the private sector and so there are no particular restrictions on health professionals moving to the UK from the private sector.

While India is not on the red list for recruitment, it is clear that the Indian public health system could significantly benefit from these qualified staff. Despite India being a health powerhouse for the world in terms of health services and professionals, India’s public health system is considered to be lacking in terms of quality and performance: low in human resources (trained health professionals opt to work in the private sector), suffering from high levels of corruption, lacking essential medicines and services, with limited interventions at primary care levels[42]. Ensuring health care delivery to the Indian population is problematic given that 40% of India’s population live below the poverty line[43]. Infant and maternal mortality rates are very high. The poor[44] suffer from lack of access to highly developed and quality health services and sometimes the most basic healthcare is not available. Since independence from Britain in 1947, India’s health care system has certainly not benefited the poorest with clear segmentation introduced as private health services have grown. Quality health care is considered to be an issue according to the WHO[45]. The Clinical Establishments Act of 2010 was supposed to set minimum standards for diagnosis and treatment for all health facilities across India. However, these quality standards have still not been implemented by the majority of states. In addition, drug regulation is considered to be poor and pharmaceutical prices subject to price escalation[46]. It has been reported that India has over 1.25 million doctors, but only 100 000 work in the public health care sector. The doctor to patient ratio in the UK is considered to be low in comparison to the OECD average but in comparison to India, the ratio is significantly higher (1 to 1000 doctors in India ratio compared to 2.8 to 1000 in the UK)[47].

Protecting migrant workers’ rights

In addition to the risk of depriving a relatively less effective public health system of workers, there is concern over the rights of migrant health workers from India. There is indeed concern that the General Agreement on Tariff in Services (GATS) and other global regulations do not sufficiently address problems of exploitation and the rights of individuals to health. In order to ensure protection of workers, India has signed agreements on labour mobility with a number of European countries, including the UK such as the Code of Practice described above but these have not prevented the negative impacts of health personnel mobility. In addition, to attempt to deal with accusations of profiting from overseas staff, the UK took several approaches to international recruitment and underlined the importance of ethics in recruitment through bilateral agreements. Indeed, traditionally, migrant workers who came to the UK in the 1960s were all given work at a lower grade and encouraged to stay in non-career grades with visas limiting job opportunities[48]. The Code of Practice published in September 2001 stipulated that international recruitment should be strictly regulated by formal agreements with that country[49]. It stipulated that staff should have the same opportunities for professional development as other employees. However, the Code excluded the private sector. Private recruitment agencies therefore do not need to respect the Code of Practice. In 2022, a new framework to collaborate on healthcare workforce objectives by enhancing bilateral co-operation in capacity building, exchange of ideas and expertise across all areas of healthcare workforce was also signed. While this does not offer solutions to the brain drain issue, it aims to ensure good working conditions and equal rights for workers[50]. Nevertheless, certain forms of exploitation have been reported, notably high exit fees for NHS nurses[51]. Indeed, NHS Trusts which recruit international nurses have included clauses in contracts if they leave their roles before a set period of time (some up to five years and penalities of up to £14,000 have been levied). This is in order not only to retain staff but also owing to the high recruitment costs of hiring overseas staff such as flights to the UK, visas, language proficiency exam fees and mandatory training required for non-UK workers. Some employers have allegedly tried to frighten and intimidate staff through threats of deportation if they leave[52].

Moreover, these Codes of Practice may well fall short of effective plans to deal with staff who face significant acculturation issues (the psychological and emotional issues linked to adapting to a new culture), racism or rejection. Very few studies exist about the specific issues of health workers with the exception of the aforementioned study by Alonzo and Mayben[53], which concentrated essentially on push and pull factors. However, by extrapolating risk factors for health care migrants from India from the general literature on migrant wellbeing, we can expect that some socio-environmental variables could seriously compromise mental health of international health care workers. Mucci et al.’s systematic review of the literature showed that migrants suffer from more psychotic, mood, anxiety disorders and in some cases post-traumatic disorders. While economic migrants arriving with a firm job offer may not suffer the same stresses as asylum seekers, we might expect some significant issues related to the difficulties to adapt given the geographical and cultural distance from India. Moreover, transition to urban areas has shown to cause significant psychophysical stress in the literature[54]. Added to this, distance from family and discrimination, particularly in the environment of post-Brexit Britain, could impact on the overall wellbeing of these migrants[55].

Risks to the National Health Service (NHS) of the transnational policy of recruitment

Recruiting staff from India is a major advantage for the UK, thanks to the ready supply of highly skilled health workers which Britain has not had to pay to train. Many of the negatives thus fall on the home country. However, some risks to international recruitment have been identified for the NHS. First, if other countries start to recruit more staff (notably the United States) and offer higher wages or more comfortable working conditions, this may reduce the supply to the UK or lead to out migration. Second, once the workers receive indefinite leave to remain in the UK, they may well follow other NHS workers who have often switched to the private sector or other sectors owing to the difficult working conditions NHS staff are facing (overwork, pay which has not kept up with inflation, organisational change, etc.) Third, the continued reliance on international recruitment is not addressing the underlying issues of retention of domestic workers[56]. While skills are on the whole assured thanks to the accreditation by Ecctis, some issues still remain in ensuring that the right skill sets can be adapted to the everevolving health care setting in the UK. As the British General Medical Council underlined during the negotiations of the recently signed Free Trade Agreement (FTA) between the two countries, while mutual recognition of professional qualification is important, patient safety must still be at the forefront when recognising qualifications. The role of health care regulators remains vital to maintain control over registers. The reinforcement of the 2024 Medical Licencing Assessment was indeed a step in this direction to ensure a common threshold of safe practice[57]. Finally, the current backlash against immigration in the UK, exemplified by the decision to leave the European Union with the need to reduce immigration being a key factor in the decision, suggests that the UK is perhaps a less welcoming place for international workers.

Conclusions

The recent significant intake of international workers in the NHS and social care attempts to fill the shortfall in healthcare staff in UK. However, it can bring with it significant risks namely for health systems and the migrant workers themselves. While ethical standards have been established in the cross-national supply of health workers, these frameworks may well not go far enough in protecting health systems and workers. As Chanda argued more than two decades ago, a combination of bilateral, regional and multilateral cooperation is required to prevent a brain drain in the cross-border flows of health care professionals (i.e. special visa schemes and recruitment programmes, temporary flows rather than permanent flows)[58]. She also contended that bilateral cooperation would enable the host country to negotiate technical and financial assistance to the source country. Such discussions could also be included in multilateral and bilateral agreements, especially as regards the movement of health personnel. To curb a brain drain, countries should have certain negative incentives such as migration taxes whereby emigrating professionals must refund government for training costs or positive incentives such as tax exemptions, improvements in working conditions, facilities and professional opportunities. Return of talent programmes could also be set up through contracts and there could also be “brain gain” networks created. It is also important to shore up links between public and private health services in sharing information and expertise and cross-subsidisation. These further actions could well be considered in relation to the significant supply of Indian workers to the UK. In addition to these important considerations, full integration of migrant workers and acculturation issues also need to be taken into consideration. Further research and empirical studies could shed light on the specific difficulties international recruitment raises for the workers and health systems with interviews with migrant workers in a post-Brexit context. This article focused specifically on healthcare workers in the NHS but research on the specific status of care workers outside the NHS is also vital given the weight of foreign-born care workers in the UK. It remains to be seen whether the impetus of Starmer’s government to drastically reduce international recruitment will lead to a real reduction given the shortage of staff set to continue for the future.

___

NOTES

[1] KINGSFUND, The NHS workforce in a nutshell, 10 May 2024, [https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/insight-and-analysis/data-and-charts/nhs-workforce-nutshell].

[2] The MIGRATION OBSERVATORY, Migration and the health and care workforce, 27 June 2023, [https://migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/resources/briefings/migration-and-the-health-and-care-workforce/].

[3] Reported in The MIGRATION OBSERVATORY, op. cit.

[4] Denis CAMPBELL, “NHS in England told to slash recruitment of overseas-trained medics », Guardian Online, 2 July 2025.

[5] OECD, “Recent Trends in International Migration of Doctors, Nurses and Medical Students”, Paris : OECD, 2019, [https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/recent-trends-in-international-migration-of-doctors-nurses-and-medical-students_5571ef48-en/full-report/component-3.html#section-d1e313].

[6] International Political Economy (IPE) studies how politics shapes the global economy and vice versa how the global economy shapes politics.

[7] Human Resource Literature (HHR) studies issues around human resources such as workforce planning and policy evaluation, recruitment and retention, training and development of skilled personnel, etc.

[8] Margaret WALTON-ROBERTS, “International migration of health professionals and the marketization and privatization of health education in India: From push–pull to global political economy”, Social Science & Medicine, 124, 2015, pp. 374-382, [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.10.004].

[9] Ibid.

[10] According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, the Global South is used to define historically less developed countries notably located in Latin America, Africa, the Middle East, excluding Israel, Asia and Oceania.

[11] Justin POWELL, Nadine BERNHARD, and Lukas GRAF, “The emergent European model in skill formation comparing higher education and vocational training in the Bologna and Copenhagen processes”, Soc. Educ. 85 (3), 2012, pp. 240-258.

[12] Margaret WALTON-ROBERTS, op. cit.

[13] Parvati RAGHURAM, “Which Migration, What Development? Unsettling the Edifice of Migration and Development”, Population Space Place 15, 2009, pp. 103-117.

[14] Salimah VALIANI, “South-North Nurse Migration and Accumulation by Dispossession in the Late 20th and Early 21st Centuries”, World Review of Political Economy, 3(3), 2012, pp. 354-75, [https://doi.org/10.13169/worlrevipoliecon.3.3.0354].

[15] Margaret WALTON-ROBERTS, op. cit.

[16] Alvaro ALONSO-GARBAYO and Jill MABEN. “Internationally recruited nurses from India and the Philippines in the United Kingdom: the decision to emigrate” Human Resources Health, 7 (37), 2009, DOI: [10.1186/1478-4491-7-37].

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Parvati RAGHURAM, “Which Migration, What Development? Op. cit.

[21] Margaret WALTON-ROBERTS, op. cit.

[22] Barbara STILWELL, Khassoum DIALLO, Pascal ZURN, Marko VUJICIC, Orvill ADAMS, Mario DAL POZ, “Migration of health-care workers from developing countries: strategic approaches to its management”, Bull World Health Organ. 82, 13 August 2004, pp. 595-600.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Simplice ASONGU, “The impact of health worker migration on development dynamics: Evidence of wealth effects from Africa”, The European Journal of Health Economics 15(2), 2014, pp. 187-201. DOI: [https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-013-0465-4]. Waleed SWEILEH, “Research Trends and Patterns on International Migration of Health Workers (1950–2022)”, SAGE Open, 14(4), 2024, DOI: [https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440241293190].

[25] Shaista AFZAL, Imrana MASROOR, Gulnaz SHAFQAT, “Migration of health workers: A challenge for health care system”, Journal of College of Physicians and Surgeons 22(9), 2012, pp. 586–587; Roland M. DIMAYA, Mary K. McEWEN, Leslie A. CURRY and Elisabeth H BRADLEY, “Managing health worker migration: A qualitative study of the Philippine response to nurse brain drain”, Human Resources for Health, 10, 19 December 2012, [https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-10-47]; SWEILEH, op. cit.

[26] Barbara STILWELL et al., op. cit.

[27] Simplice ASONGU, op. cit.

[28]Lena DOHLMAN, Matthew DIMEGLIO, Jihane HAJJ, Krzysztof LAUDANSKI, “Global brain drain: How can the Maslow theory of motivation improve our understanding of physician migration?”, The International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(7), 2019, p. 1182, DOI: [https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16071182]; Tega EBEYE and Haeun LEE, “Down the brain drain: A rapid review exploring physician emigration from West Africa”, Global Health Research and Policy, 8(1), 23, 2023, DOI: [https://doi.org/10.1186/s41256-023-00307-0]. Waleed SWEILEH, op. cit.

[29] Lars E. HAGANDER, Christopher D. HUGHES, Katherine NASH, Karan GANJAWALLA, Allison LINDEN, Yolanda MARTINS, Kathleen M. CASEY, John G. MEARA, “Surgeon migration between developing countries and the United States: train, retain, and gain from brain drain”, World J Surg. 37(1), January 2013 :14-23. DOI: [10.1007/s00268-012-1795-6. PMID: 23052799].

[30] Barbara STILWELL, op. cit.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Margaret WALTON-ROBERTS, op. cit.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Alvaro ALONSO-GARBAYO and Jill MABEN, op. cit.

[38] Preeti VERMA, “Immigration Update: What you need to know about the UK’s health & care visa”, Hindustan Times, 10 January 2024, [https://www.hindustantimes.com/education/employment-news/immigration-update-what-you-need-to-know-about-the-uk-s-health-care-visa-101704867507105.html].

[39] UK Visas and Immigration, Health and Care Worker Visa, 2024, [https://www.gov.uk/health-care-worker-visa].

[40] Barbara STILWELL et al., op. cit.

[41] NHS EMPLOYERS (2025), Quick guide: Code of Practice for International Recruitment, [https://www.nhsemployers.org/publications/quick-guide-code-practice-international-recruitment].

[42] WHO, India health system review, 30 March 2022, [https://apo.who.int/publications/i/item/india-health-system-review].

[43] Ibid.

[44] The poverty line in India is estimated based on consumption levels and not revenue which means that it assesses the minimum level of food, clothing, educational and medical needs, etc. Minimum consumption is then calculated in Rupees to assess minimum needs and thus the classification of poverty.

[45] Ibid.

[46] WHO, op. cit.

[47] Ibid.

[48] Polly TOYNBEE, Hard work: Life in low-pay Britain, London, Bloomsbury, 2003.

[49] DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, “Tackling racial harassment in the NHS: Evaluating black and minority ethnic staff attitudes and experiences”, 2001, [http://www.doh.gov.uk/raceharassment/evaluatingreport.pdf].

[50] DEPARTMENT FOR INTERNATIONAL TRADE, UK and India collaboration on healthcare workforce framework agreement, 23 July 2023, [https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/uk-and-india-collaboration-on-healthcare-workforce-framework-agreement].

[51] The MIGRATION OBSERVATORY, Migration and the health and care workforce, 27 June 2023, [https://migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/resources/briefings/migration-and-the-health-and-care-workforce/].

[52] Chanti DAS, “Overseas nurses in the UK forced to pay out thousands if they want to quit jobs”, Observer, 27 March 2023.

[53] Alvaro ALONSO-GARBAYO and Jill MABEN, op. cit.

[54] Nicola MUCCI, Veronica TRAVERSINI, Gabriele GIORGI, Eleonora TOMMASI, Simone DE SIO, and Giulio ARCANGELI, “Migrant Workers and Psychological Health: A Systematic Review”, Sustainability 12 (1), 2020, p. 120, DOI: [https://doi.org/10.3390/su12010120].

[55] Ibid.

[56] MIGRATION OBSERVATORY, op. cit.

[57] GENERAL MEDICAL COUNCIL (GMC), “GMC response to consultation on trade negotiations with India”, July 2021, V10866/Documents/Trade%20conference%202024/my%20article/GMC-response-to-consultation-on-trade-negotiations-with-India—July-2021-86917702.pdf].

[58] Rupa CHANDA, “Trade in Health Services”, Bulletin of the World Health Organisation, 80 (2), 2002, pp. 158-163.

Bibliographie

DAS Chanti, “Overseas nurses in the UK forced to pay out thousands if they want to quit jobs”, Observer, 27 March 2023.

HAGANDER, Lars E., Christopher D. HUGHES, Katherine NASH, Karan GANJAWALLA, Allison LINDEN, Yolanda MARTINS, Kathleen M. CASEY, John G. MEARA, “Surgeon migration between developing countries and the United States: train, retain, and gain from brain drain”, World J Surg. 37(1), January 2013, pp.14-23. DOI: [10.1007/s00268-012-1795-6]. PMID: 23052799.

HINDUSTAN TIMES, “Immigration Update: What you need to know about the UK’s health & care visa”.

KINGSFUND, “The NHS workforce in a nutshell”, 10 May 2024, [https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/insight-and-analysis/data-and-charts/nhs-workforce-nutshell].

MUCCI, Nicola, Veronica TRAVERSINI, Gabriele GIORGI, Eleonora TOMMASI, Simone De SIO, and Giulio ARCANGELI, “Migrant Workers and Psychological Health: A Systematic Review”, Sustainability 12 (1), 2020, p. 120, DOI: [https://doi.org/10.3390/su12010120].

NHS Employers, 2025, “Quick guide: Code of Practice for International Recruitment”, [https://www.nhsemployers.org/publications/quick-guide-code-practice-international-recruitment].

OECD, “Recent Trends in International Migration of Doctors, Nurses and Medical Students”, OECD, Paris, 2019, [https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/recent-trends-in-international-migration-of-doctors-nurses-and-medical-students_5571ef48-en/full-report/component-3.html#section-d1e313].

POWELL, Justin, Nadine BERNHARD, and Lukas GRAF. “The emergent European model in skill formation comparing higher education and vocational training in the Bologna and Copenhagen processes”, Soc. Educ. 85 (3), 2012, pp. 240-258.

RAGHURAM, Parvati, “Which Migration, What Development? Unsettling the Edifice of Migration and Development”, Population Space Place 15, 2009, pp. 103-117.

STILWELL, Barbara, Khassoum DIALLO, Pascal ZURN, Marko VUJICIC, Orvill ADAMS, Mario DAL POZ, “Migration of health-care workers from developing countries: strategic approaches to its management”, Bull World Health Organ. 82, 13 August 2004, pp. 595-600.

SWEILEH, Waleed, “Research Trends and Patterns on International Migration of Health Workers (1950–2022)”, SAGE Open, 14(4), 2024.

The MIGRATION OBSERVATORY, Migration and the health and care workforce, 27 June 2023, [https://migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/resources/briefings/migration-and-the-health-and-care-workforce/].

TOYNBEE, Polly, Hard work: Life in low-pay Britain, London, Bloomsbury, 2003.

UK VISAS AND IMMIGRATION, Health and Care Worker Visa, 2024, [https://www.gov.uk/health-care-worker-visa].

VALIANI, Salimah “South-North Nurse Migration and Accumulation by Dispossession in the Late 20th and Early 21st Centuries”, World Review of Political Economy, 3(3), 2012, pp. 354-75, DOI: [https://doi.org/10.13169/worlrevipoliecon.3.3.0354].

VERMA, Preeti, “Immigration Update: What you need to know about the UK’s health & care visa”, Hindustan Times, 10 January 2024, [https://www.hindustantimes.com/education/employment-news/immigration-update-what-you-need-to-know-about-the-uk-s-health-care-visa-101704867507105.html].

Auteurs

Louise DALINGWATER

Sorbonne Université, Histoire et dynamique des espaces anglophone (HDEA), EA 4086

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4798-5332

louise.dalingwater @ sorbonne-universite.fr

Références

Pour citer cet article :

Louise DALINGWATER - "Louise DALINGWATER, Increasing the international supply of workers post Brexit and the impact on the health sector" RILEA | 2025, mis en ligne le 01/12/2025. URL : https://anlea.org/revues_rilea/louise-dalingwater-increasing-the-international-supply-of-workers-post-brexit-and-the-impact-on-the-health-sector/