Résumé

Donner la parole aux travailleurs : les défis des travailleurs de la santé en Grande-Bretagne

Au cours des dernières décennies, le monde du travail britannique a dû s’adapter à de profonds changements. La main-d’œuvre elle-même a également changé avec une plus grande participation des femmes, un plus grand nombre de familles où les deux conjoints travaillent et des travailleurs plus âgés en raison de la réduction des pensions de retraite et de l’augmentation de l’âge de la retraite. Tous ces changements ont eu un impact significatif sur le monde du travail dans tous les secteurs d’activité. Cet article se concentre sur le secteur des soins de santé, qui emploie un pourcentage important de la main-d’œuvre britannique. Il s’intéresse tout particulièrement aux changements intervenus dans ce secteur et à leur impact sur les travailleurs britanniques. Une série de réformes des soins de santé a transformé les modèles et les pratiques de travail dans le secteur de la santé publique britannique, et notamment dans le National Health Service (NHS), en ce qui concerne l’organisation, la structure, le financement et la réglementation[1]. À partir des années 1980, le NHS est entré dans ce qu’Allen a décrit comme une ère managériale, ouverte à une évaluation et à un contrôle renforcé selon les principes néolibéraux d’efficacité et de rationalisation[2]. L’impact sur le personnel de santé a été important. Cet article propose donc de passer en revue la littérature sur les défis actuels et futurs pour les travailleurs du secteur public des soins de santé, en s’appuyant notamment sur des documents gouvernementaux relatifs au secteur de la santé, des rapports d’organisations internationales telles que l’OIT, des documents d’organismes professionnels et de syndicats et d’autres documents secondaires pertinents, notamment dans le domaine des sciences sociales et politiques. Il analyse ensuite huit entretiens et dix questionnaires auto-administrés afin de donner la parole aux travailleurs de la santé. Il adopte une approche multidisciplinaire de l’analyse des soins de santé.

Mots-clés : travailleurs, soins de santé, Grande-Bretagne, NHS, pénurie des travailleurs, santé numérique

Abstract

Over the past few decades, the British workplace has had to adapt to profound changes. The workforce itself has also changed with greater female participation, a higher number of dual earners and older workers still present in the labour market because of reduced pensions and increased retirement ages. These changes have all had a significant impact on workers across industries. This article will focus on the health care sector which employs a sizeable portion of the global workforce. It is particularly interested in the changes in this sector and the impact on workers in Britain. A series of reforms in health care have transformed working patterns and practices in Britain’s public health sector, and notably in the National Health Service (NHS), relating to organisation, structure, funding and regulation[3]. From the 1980s onwards, the NHS entered what Allen[4] has described as a managerialist era, open to significant evaluation and control along neoliberal lines of efficiency and rationalisation. The impact on healthcare staff has been significant. This article thus proposes to review the literature on present and future challenges for workers in the public health care sector, especially drawing on government documents on the health sector, international organisations’ reports such as the ILO, professional bodies’ and trade union documents and other relevant secondary literature namely in social and political science. It then analyses eight in depth interviews and ten self-administered questionnaires to give a voice to health care workers on present and future conditions at work. It thus aims to take a multidisciplinary approach to health care analysis.

Keywords: workers, health care, Britain, NHS, staff shortages, digital health

—

NOTES

[1] R. LEVITT, A. WALL and J. APPLEBY, The Reorganized National Health Service (sixth edition), Cheltenham: Stanley Thornes, 1999; P. LEONARD, “Playing’ Doctors and Nurses? Competing Discourses of Gender, Power and Identity in the British National Health Service”, The Sociological Review, 51(2), 2003, p. 218-237. [DOI:10.1111/1467-954X.00416].

[2] D. ALLEN, The Changing Shape of Nursing Practice, London: Routledge, 2001.

[3] R. LEVITT, et al., op. cit.; P. LEONARD, op. cit.

[4] D. ALLEN, op. cit.

Texte

Introduction

Over the past few decades, the global work force has had to adapt to profound changes: imperatives to compete with overseas labour markets in light of globalisation, advances in information technology, organisational restructuring, the introduction of more varied and flexible work contracts, changes in worktime scheduling and flexible working. The typology of the workforce has also changed with greater female participation, a higher number of dual earners and older workers still present in the labour markets because of reduced pensions and increased retirement ages. Specifically in Britain, the employment rate for people aged 50 to 64 years has increased steadily since the mid-1990s, rising from 57.2% in 1995 to 71.2% in 2021[1]. These changes have all had a significant impact on the workplace across industries. This article will concentrate on the health care sector in Britain which employs a sizeable portion of the global workforce. One in ten jobs are now in health or social care.[2]

A series of reforms in health care have transformed working patterns and practices in Britain’s public health sector, and notably the National Health Service (NHS) relating to organisation, structure, funding and regulation[3]. This article thus proposes to review the literature on present and future challenges for workers in the public health care sector, especially drawing on government documents on the health sector, international organisation reports such as the ILO, professional bodies and trade union documents and other relevant secondary literature, namely in social and political science. It then analyses eight in depth interviews and ten self-administered questionnaires to give a voice to health care workers on present and future conditions at work.

To study these discourses, we adopt a simple content analysis approach[4], defining several thematic categories. This method enabled us to identify both convergences and divergences in relation to the general discourse on challenges in the work place identified in the literature. At the same time, it also highlights variants between the discourses of actors in the British healthcare sector, relating essentially to organisational change and digitalisation in the health sector.

The health sector in Britain and changing patterns of work

Like many developed nations, Britain has had to grapple with the growth of an ageing population in relation to the working population. While there has been a decline in infectious diseases over the last few decades, there has been a significant increase in non-communicable diseases, and notably chronic illnesses such as diabetes and, especially in old age, Parkinson’s Disease and Alzheimer’s.[5] In addition, the Covid-19 pandemic has exacerbated already existing health inequalities and poor health performance in Britain, with Britain recording one of the highest death rates per capita. The future is fairly bleak in terms of health performance, particularly given the likely fallout from the pandemic, which will add to the already existing problems, owing to excess mortality, postponement of screening and treatment for life-threatening illnesses such as cancer. Persisting health problems have also been evident since the beginning of the pandemic, and notably long Covid.[6] The British health care workforce therefore has to cope with all these issues and will be under increasing pressure to do so in coming years in order to respond to the needs of the British population.

Moreover, in Britain’s publicly funded health care system, a series of reforms in health care transformed working patterns and practices relating to organisation, structure, funding and regulation.[7] Legislation in the NHS brought in since the 1980s has moved this institution towards a marketised system, whereby the private market plays a greater role in the provision of health care. Reforms were based on the critique by Margaret Thatcher’s New Right government that the public sector was inefficient and it was important to achieve efficiency gains by adopting the principles and practices of the private sector. Competition, choice and cost-effectiveness were therefore significant principles of this new approach and healthcare staff were compelled to follow the same objectives related to these criteria. The result was that staff or sections of health care providers were forced to compete for funding and resources in line with market principles. In addition, staff were constantly called upon to improve services according to specific output objectives and evaluation criteria. In 1990, to achieve such results, an “internal market” was created in the NHS whereby the purchasers of healthcare were separated from the providers. That is, General Practitioners (GPs) were called upon to assess what treatment the patient needed, then the treatment was purchased from a health care provider according to an annual budget. Health care providers were thus in competition with each other with an aim to ensure greater cost-efficiency[8]. Another clear example of marketisation was the Health and Social Care Act in 2012. Since the introduction of this legislation, market mechanisms have played an even greater role in the NHS. In particular, section 75 of this Act requires commissioners to tender out all services. Since the promulgation of this Act, private contractors have been more likely than public service providers to win these calls because they are able to offer “better value for money”. From the 1980s onwards, the NHS thus entered what Allen[9] (2001) has described as a managerialist era, open to significant evaluation and control along neoliberal lines of efficiency and rationalisation.

The impact on health care staff has been significant to such an extent that Buetow and Rolan[10] claim that workers are forced to assume managerial approaches in order to reach the imposed goals and targets (relating to waiting times, reductions in hospital stays…). A number of studies have shown that the emphasis on performance management techniques with metrics-bases target systems has lowered workforce morale and even led to system failures.[11] The next section will thus examine in more detail the impact such transformations and other global imperatives (digitalisation, etc.) have had on the health care workforce drawing on a wealth of secondary literary in political and social science, government policy documents, international organisations’ position papers, documentation from professional and inter-professional organisations…

Health care jobs: retention, quality and deprofessionalisation

Understaffing and difficult working conditions

In the health sector, the debate on the number of jobs and future working conditions is somewhat different from the decline of jobs as a result of automatisation predicted for other sectors by certain economists [12]. In fact, the opposite is true, with an ever increasing need for more workers in the health sector. There is much debate about how the health sector is coping with the cumulative shortage of health care workers. Government policy documents, health and social care think tanks and the media portray a bleak future given the low retention rate of health workers and current worker shortages in the sector.[13] In a study carried out by NHS Providers[14] on worker shortages in the organisation, it was reported that executives of two thirds of hospital trusts believe that the most significant challenge to delivering high quality healthcare is the lack of staff. Irrespective of technological change and the possibility of automating some tasks, policy documents contend that the health sector will continue to require significant manpower, so this can be seen as both a present and future challenge.[15] This is in stark contrast to much of the economic literature which underlines present and future declines in jobs and job polarization with advances in technology and globalisation.[16] In the health sector, the number of staff has actually increased in recent years. The number of doctors working in Britain has increased by 26.2%, nurses by 1.8% and ambulance staff by 13.3%. Yet this number is insufficient to meet the increasing demand.[17] The reason for an increase in demand in this sector can be explained by the fact that health care services and particularly public health care services are relatively sheltered from international competition. However, the overriding reason is the increase in demand for health care services with an ageing population and the development of a significant number of chronic illnesses which require the intervention of both health and social care professionals. These demands are set to increase and put extra pressure on health care systems. A British Medical Association (BMA)[18] study reported 124 000 unfilled vacancies in secondary care in June 2022.[19]

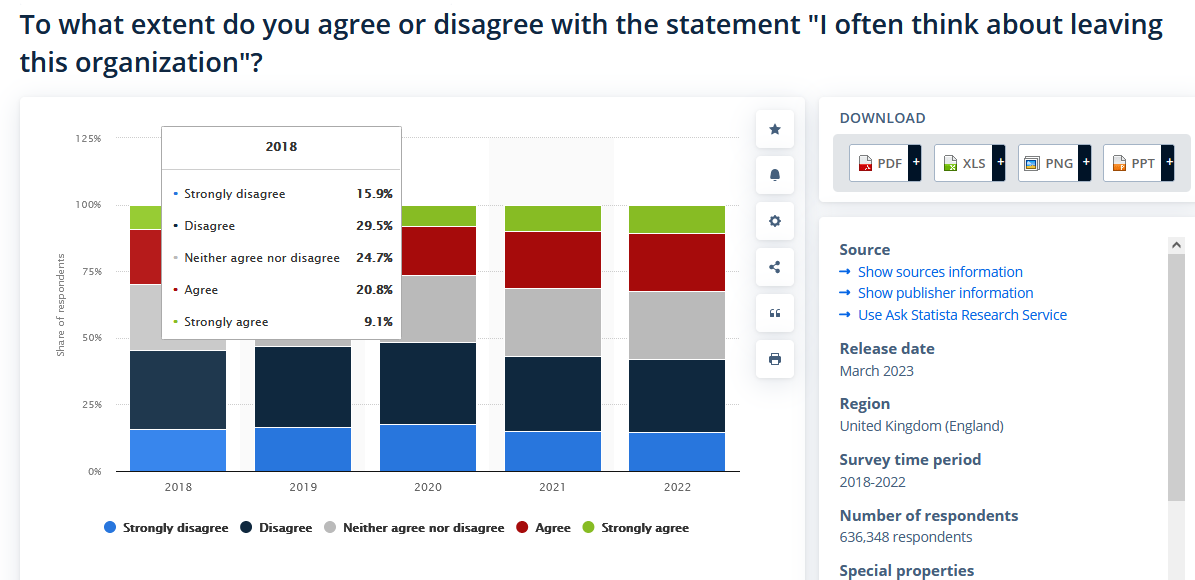

The supply has thus not kept up with the demand and the pressure to do overtime has been significant. Difficulties in retaining workers are linked to the long hours and the lack of a work-life balance: 59% of workers reported working long hours.[20] Also job quality is very much an issue as people’s reported experience of health care work in the published literature tends to be negative, looking at increased factors like stress, violence, excessive workload and absenteeism. A vast literature on the subject especially written by social scientists and health policy analysts has shown that organisational and legal changes can have an impact on autonomy and wellbeing because of changing guidelines and performance measures, performance pay and the like, which can increase stress and workloads.[21] Organisational change fatigue is considered to express itself, for example, through apathy, disengagement, exhaustion and burnout during and after periods of organisational change. In some cases, it can lead to departure and staff shortages and the risk of future shortages. According to a 2022 Statista survey, approximately a third of NHS staff have often thought about leaving the NHS:

Figure 1 – Survey

Source: STATISTICA, “NHS Staff Shortages”, November 2023, https://www.statista.com/topics/9575/nhs-staff-shortage/

The current British government has proposed to increase medical education, expand the number of placements for nurses and healthcare students and offer apprenticeships as more attractive and less expensive healthcare training processes. It is not sure that this will solve the fundamental issue of lack of supply given the aforementioned workplace challenges of burnout, stress and difficult conditions[22]. Alternatively, trying to increase international supply has been a key policy approach of the current British government, with specific health and care visas being created after the UK’s departure from the EU. Yet Brexit and global uncertainties have undermined such recruitment in terms of the future of health care recruitment from abroad. Another solution has been to push for greater variety of job descriptions through reclassification and deprofessionalisation.

Deprofessionalisation

Deprofessionalisation can be described as the process in which well-established professional occupations no longer have autonomous control over internal affairs and the behaviour of membership. There are no longer exclusive rights to do certain kinds of work in these professions. In the process, there is a loss of control over expert knowledge. Deprofessionalisation is seen to be significant in the public sector since the introduction of market-led reforms in the 1980s.[23] This has involved the fast track training of professionals with reduced theoretical training. In practice, this has meant the downgrading of the public service professions with community wardens and Police Community Support Officers (PCSOs) taking on policing tasks. In schools, Classroom and Teaching Assistants are increasingly called upon to take over teaching tasks, and Social Work Assistant and Family Workers have taken over the role of registered social workers. These new professions enable governments to cut costs in terms of human resources because it is cheaper to train and employ such workers than established public sector professionals.[24] Such transformations are also very significant in the health sector. Within the British health care setting, there are divisions between medical work, which has traditionally been given high status and more professional autonomy, and care work which is less valued. These can be subdivided into several categories according to qualifications: nurses, “professional careworkers”, who have been able to reach managerial rank and “careworkers”, without the professional title and who are given fairly low status.[25] In fact, since the 1980s and the managerial approach to health care systems, we can observe a shift in workloads from high reward professionals to lesser skilled and lower paid groups. Some responsibilities, which were originally solely the domain of professional care workers, have been shifted to non-professional care workers.[26]

Research on the effects of this have shown that nurses have lost out the most with a constant struggle to obtain professional status.[27] Perhaps one of the reasons to explain this is that nurses’ skills are considered to be nebulous and therefore tend to be exploited by the state or by local managers.[28] An increase in responsibilities for nurses has led to a reduction in the total number of hours junior doctors work, so the landscape for nurses has considerably changed.[29] Since the 1990s, extensive prescribing rights have been given to nurses, which has allowed physicians to free up time to attend to more acute care cases.[30] While plans are underway to recruit more and offer more diverse roles in health care, the newly trained staff need to have the knowledge and capacity to manage complex medical questions. Moreover, for the moment there is no formal legislation on the roles such associates should play. Nursing associates have already been employed to address gaps in skills and knowledge to deliver nursing care, so that registered nurses can attend to more complex care, but again legislation is not very tight.[31]

The literature thus predicts continued deprofessionalisation in the future to cope with cost and shortage of supply.[32] Beyond funding imperatives for change is the technologically deterministic discourse and the documents describe an inevitable shift to non-professional staff in the future. Proposals have been made to increase the number of generic workers, that is a major expansion of non-professional staff. It has been estimated that 40% of the health workforce will be generic carers in the future as a result of workforce shortages in the health sector[33]

As the ILO argues:

NSFE[34] are likely to grow in the health services sector due to the increasing shortage of health professionals and expectations of work-life balance. Zero hours contracts[sic], an arrangement whereby workers do not have guaranteed working hours, are on the rise. In 2013, some 27 % of healthcare employers in the United Kingdom were using zero hours contracts [sic]. Initially used in low-skilled jobs, zero-hours contracts [sic] are increasingly being used in cardiac services, physiotherapy, psychiatric therapy, and hearing services.[35]

Digitalisation could also lead to further deprofessionalisation or declassification of health sector jobs.

Automation and workplace change

Digital transformations

The health sector has been relatively slow to adapt to digital technologies compared to other service sectors, although health technology has been central to health care provision for many years, and especially since the 1970s, with the introduction of scans and computer technology for administrations.[36] But there has been a significant increase in the use of digital health devices since the beginning of the Covid 19 pandemic. Digital health refers to the use of a wide range of technology: teleconsultation, remote monitoring, connected devices, digital health platforms, health apps, health data analysis, application in systems based on big data in epidemiological research and AI-enabled diagnosis support.[37] The pandemic did indeed lead to an increase in home consultations, telemedicine technology to diagnose and treat patients and more E-prescriptions.[38] Yet health technologies raise challenges for health care workers and are set to raise challenges for the future as health services increase their use of digital technologies.

The subordination of workers to technology is a particular theme which is relevant to all sectors. From the health workers’ perspective, new models of care which rely on technology are expected to help shape future planning models and to ensure sufficient staff with the appropriate skills.[39] Fernandes et al. predict for example that robotics will alter the way that physicians work and clinicians will have to be able to cope with machine learning with diagnostics. The review of AI in healthcare (Topol Review) forecast that natural language processing will be widely used by 2030 and automated image interpretation and predictive analytics by 2035.[40]

In many policy papers from the WHO, ILO, government documents and NHS reports, the technologically deterministic discourse is present. In the policy documents, technology change is seen to drive organisational change as much as cost. Such changes to the way that health care is administered include developments in surgical techniques, developments in telemedicine and telehealth allowing consultations and procedures to be carried out remotely. In Britain, health ministers have continually used technic centric discourse and ambitious visions to push the digitalisation of health service. For example, former health minister, Sajid Javid underlined how the new NHS health app will revolutionise health care:

The NHS App will be at the heart of these plans. We saw during the pandemic how people grasped the opportunity to have healthcare at their fingertips. I am determined to make this app the front door to NHS services, and this plan shows how we will add an array of new features over the coming years, with new functionality and more value for patients every single month. My vision is one in which the app is an assistant in your pocket.[41]

Also in a statement made by the NHS to the House of Lords committee, it was argued that: “New innovative digital ways of working–from advanced robotics right down to simply upgrading computing hardware–have the potential to free up staff to spend more face-to-face time with patients. Along with other transformations underway, this will lead to a more sustainable health service”.[42]

Yet those carrying out fundamental research in the field underline the challenges for workers in the technological transition in the health sector. Researchers Wolfgang Fruehwirt and Paul Duckworth at Oxford Robotics Institute interviewed healthcare practitioners and found that those working in the field found more caveats in the ability to fully automate healthcare work than technical experts.[43] In 2022, a British Medical Association report (BMA) also summarised the views of doctors on the ability to achieve the digital transformation ambitions set by governmental and international institutions, but also those that would allow patients to fully assess digital health services. The doctors reported that despite the desirability for change, transformation within healthcare services was impeded by an outdated, archaic IT estate especially in secondary care.[44] The ILO document on the future of work in the health sector also takes a more nuanced approach to the digital revolution:

While health technology can contribute to cost containment, it has added to healthcare expenditure growth in recent years in OECD countries. Evidence of the effectiveness and utility of new technologies is not always clear, and policy-makers must balance innovation with value.[45]

In addition, health care workers will find it difficult to ensure access to care for vulnerable populations because of the digital divide. Stone[46] underlined that access depends on the infrastructure in a person’s home or mobile servers. People living in deprived communities or rural areas may have difficulty accessing online services. They may also experience reduced access because of lack of skills and/or mistrust of technology. Yates et al.[47] identified a regional divide in Britain in terms of access. While 49% of the population had full access to the Internet in the South East, only 18% were connected in the North East and 31% in the North West.[48] In addition, the authors also found that factors relating to age, gender, income, employment and education had a significant impact on the digital divide. Marginalised groups were found to be particularly limited in their access to online services.[49]

Upskilling

As well as the drive towards technology to improve efficiency in the health sector, upskilling is seen as the panacea to adapt to the new future of work and increased automation in the health sector. Upskilling can be defined as the process of learning new skills or fine tuning existing skills so that employees can continue to conduct their work efficiently.[50] Such a process may be required in order to be able to use new medical and healthcare technologies which require specific digital literacy skills. In some circumstances there may be staff changes and some healthcare professionals may be required to work in different departments (this was the case during Covid 19), which may require building on already existing skill sets or learning new skills[51].

Specifically, in the health sector, government papers have underlined that the future capacity to supply health workers depends on capacity building and skills sets. In particular, in a recent policy paper, the health minister claimed:

We will relentlessly focus on digital skills and leadership and culture, at all levels, so we can make transformation durable right across the board […] This agenda matters more than it did when this pandemic began. I am determined to use the power of technology and the skills, leadership and culture that underpins it, to drive a new era of digital transformation. So our health and care system, and our country, will thrive long into the future, delivering vast benefits for patients.[52]

Such discourse on upskilling can be linked to the capacity building discourse of the knowledge economy which has underpinned neoliberal governance discourse since the 1980s. Within this framework, it is up to the individual and/or individual organisations whether it be in the health sector or elsewhere to be responsible, to self-regulate and provide the skills for the market.[53]

While upskilling is not necessarily a negative policy option, the essential onus to gain those skills is on the individual. Other rhetoric has been around boosting productivity in the health sector, again within the neoliberal line of efficiency gains.[54] The emphasis is on staying relevant and competitive rather than ensuring a duty of care in the sector.

Changing the place of delivery of care

In addition, much of the literature underlines the importance of moving care from the hospital to a community setting. It is predicted that in the future technological change and advances in medicine will mean that curative and preventative medicine will be provided outside the hospital:

In 2100, hospitals will focus on care of the sick, but the nature of health, sickness, treatment and care will be very different. Current hospital-based diagnostic services will be automated and deliverable in the home, resulting in a major shift of the burden of caring. This shift will eliminate today’s community hospital. Work of low to medium complexity will be undertaken, usually by machines, in the home. Ambulatory centres, highly automated, highly accessible, will be customer friendly one-stop health shops of tomorrow. Machines will substantially replace human labour. [55]

Robots have already started to be used in surgery and Walsh predicts this is set to increase and especially to be used for procedures which are labour intensive, repetitive and prone to human error. Nanomedicine will also enable advances in medicine. The same author claims that: “One thing is certain: hospitals of 2100 will bear no more resemblance to our current institutions than do today’s hospitals to their forbears in 1900.”[56] The remainder of healthcare delivery will, according to Walsh, be concentrated in the community: “What growth there is in health care, relative to the rest of the economy, will be directed to agents and agencies caring for those with unsound health in the community.”[57]

In the late 1990s, the British Medical Journal also devoted a series of articles to the changing hospital.[58] The articles underlined some of the reasons why there is a paucity of data or discourse on the evolving or future of the workplace in the health sector, particularly in a hospital setting. The authors of one of the articles in the series argue that change management successes are not reported because of fear of reprisals and policy recommendations difficult to make because of different local circumstances:

Little research into or evaluation of change management programmes in the NHS has been done. These subjects are difficult to research, and participants may be unwilling to expose themselves to external scrutiny. Developing generalisable lessons is difficult, particularly as local factors, especially politics, are often of great importance in determining the outcome. There are few peer reviewed journals for reporting what research does exist.[59]

Despite these subsequent predictions of hospital change, the discourse may well just amount to performative attempts to bring about rapid policy change and cut costs in providing health care in hospital settings. The above analysis has thus explored at some length the present and future challenges for workers in the public health care sector. But it is interesting to see how the workers themselves feel about the organisational changes they have undergone and the future changes to health care provision. The following specifically analyses how workers either internalise the necessity for change or call for more effective interventions to improve conditions in the workplace for the present and future.

Empirical study

Methods

The following section intends to give a voice to workers themselves about present and future conditions of work. It presents a qualitative empirical study carried out in the United Kingdom among health care workers, namely those working for the NHS or working closely with this institution in the social care sector. The study does not intend to be and indeed cannot be exhaustive given the number of health care workers in the UK and the limited number of interviews. The qualitative approach is intended to draw attention to some of the aspects already studied in the literature above and show that there are indeed diverse points of view.

Participant data

Six in-depth interviews and ten self-administered questionnaires were conducted between August and September 2021 in Britain (one participant in Scotland and fifteen participants across England). One exception was a nurse who had worked in both Britain and France. The respondents were working across the primary and secondary health care sectors and the vast majority (but two) were employed by the National Health Service (NHS). Descriptive statistics of the participants are given below:

Participants (n = 16), ranged in age from 25 – 65, and included 9 females (56%) and 7 males (44%). Socio-professional categories: non-professional care/admin = 3, professional service providers, hospital and primary care executives = 7, professional service providers = 6

Study Design

The interviews were semi-structured and the interviewees were invited to reflect first on current conditions in their workplace before stating what they believed would be the defining features of the future of health care work. Participants were recruited by contacting doctor and nurse associations in Britain, through the author’s personal academic and non academic contacts and via a snowball effect. In the questionnaire and the in-person interviews, the respondents were informed that the aim of the research project was to gather qualitative analysis on present and future conditions of work in the health and social care sector.

Data analysis

To study the interviews, a simple content analysis approach was taken, defining a number of thematic categories which also enabled us to relate back these interviews to previous findings described above and thus derive meaning. In particular, the following sub-categories emerged from the analysis of the interviews: quality of work (notably underfunding and understaffing), the question of professionalisation and deprofessionalisation, automation of the work place in health care (technologically deterministic discourse and calls for upskilling), and the transition out of the hospital to community care.

Results and Discussions

Quality of work

In the interviews we noted on the whole a bleak vision of the health care sector. Negative visions of the present and the future included worsening conditions for staff and patients. These visions ranged from concern for the future to an apocalyptic vision of the end of health care provision and thus an end to health care as we know it. The specific conditions that had been described in the secondary literature would therefore seem to have a continued impact on the workers interviewed:

British nursing will become even more isolated and anomalous than it is already. On an international level it will become harder for UK trained nurses to be as mobile as they have been in the past. (Senior Nurse, Specialising in Oncology, ID, Hepatology and Occupational Health, male, 55-64)

A number of the discourses emphasised the lack of sustainability of the current system due to the pressure of population health:

I don’t think what we are doing now is sustainable. General practice is going to have to change, to reflect patient expectations, sure, but also to protect its staff.” (GP, Female, 45-54)

The NHS is not an island. We can churn through waiting lists. And we can catch up on all those. That bit won’t be an issue. We can manage that over the next few years […] but actually are we able to get into the conversation and do anything about how do we support people at home with social care and how to provide proper community infrastructure around our elderly and growing elderly population. The NHS will fall over because actually the NHS can’t operate in a vacuum and I find it absolutely extraordinary that our policy makers don’t see that. (Director of Commissioning, female, 45-54)

The above interview is reiterating the work pressures described by the professional associations in the literature. The interviewee also underlines the importance of joining up health and social care. The governmental documents described in the secondary literature called for upskilling and digital solutions, but here the interviewee is highlighting how disassociated these policy papers are from the reality. The basic infrastructure to care for the elderly is not in place which prevents front-line staff from performing essential care duties.

Front line staff focused very much on the need for more resources (financial or other) to cope with demand:

There needs to be more financial backing and support for the staff who work in the sector. I work in day services and believe there needs to be more of an understanding that the most important resource we have is the staff, without the right staff or correct level of staff a service can’t exist. (Care worker, male, 45-54)

This reflects the findings in the professional and inter-professional documents presented in the previous section for a need to increase staff and skill levels. In addition, this interviewee reflects on the lack of value given to front-line care staff and the inadequacy of solutions to deal with staff shortages.

Discourses on professionalism

Some of the interviews also focused on professional and non-professional staff working more effectively together across a system. One interviewee reported that he resented professional silos:

We’ve got to find a way of encouraging people to work across portfolios. So, for the moment if you are a hospital doctor, that’s it you’re a hospital doctor. Unless you’re a surgeon, if you’re a physician why is it that you need to be contained by the hospital, especially if you are a geriatrician or something. How do we connect those careers together? (Chief Operating Officer, Male, 45-54)

This discourse reflects Jone and Green’s[60] analysis on the need to derive meaning from the roles staff play in the workplace, and to create more meaningful working practices, but also the ability to work together as a team more effectively. As a chief executive the interviewee’s concerns are nevertheless far removed from those of frontline staff who are just trying to cope with the pressure of understaffing.

However, a Human Resources Administrator was optimistic about the possibilities and the “malleability” of the workforce giving the example of the nursing profession:

Present conditions are tough. There is increased pressures due to general ill-health of the nation and public sector budgets. However, we think up new ways to overcome these, e. g the creation of the nurse associate role; a role working higher than a HCA and assisting nurses with more responsibilities but at a lower pay than staff nurses. This has helped current HCA staff to work and train and not pay degree fees. Also international recruitment. At Leicester hospitals we have recruited over 500 overseas nurses as part of our OSCE training scheme and have retained all but a handful. The retention is much much greater than that of our national recruits. Within H&SC our defining features are to always push on and find new ways to overcome adversities”. (Administrator NHS, nurse recruitment, female, 35-44)

This statement seems to be supporting deprofessionalisation which we mentioned earlier. While it may solve some of the staffing issues, the creation of less well paid and qualified staff can have a serious impact on the quality of staff and their wellbeing in the future as the secondary literature underlined.

Indeed, other interviewees were more sceptical about the effects of organisational change on the workforce and the effects this has had on the recognition of nurses within the institution. The following interviewee makes reference to the deprofessionalisation process and the negative effects it may have:

In Scotland health is “owned” by NHS boards whereas social care is the responsibility of local authorities. We seem to be moving towards one service. I worry this leads to the dilution of nursing skills as less qualified staff will be required to take on more complex tasks. (Nurse Team Lead, female, 45-54)

Technologically deterministic discourse

A technologically deterministic discourse has been the focus of much of the general literature on work in the future, and evidence of this was also found in many of the interviews. In much of the literature, technology has been described as the agent and the people as passive subjects. Zuboff [61] noted the “relentless deluge of inevitabilist rhetoric” because of technological imperatives and the “non-negotiable advance of technology”. There was also a kind of passive inevitability of digital change in the discourses of the health care workers interviewed for the purpose of this research project.

Some were also very dubious as to how the adaptation would improve services because of a lack of skills in the workforce and/or the lack of adaptability of patients:

I think the technology is there already. We are just not very good at using it. I think this is part of what the challenge for the future is you know. We need our digital revolution. I think more and more people will become adept in time in looking after themselves via different pieces of kit and technology. How many people do you see now with an Apple Watch? How many Apple watches are connected to their GP surgery though? Very very few. (Chief Operating Officer, male, 45-54)

There is a big shift towards virtual services however these are not always appropriate in all situations. I think patient care has changed and there is now a feeling of playing catch up to an extent and we are already seeing the negative impact Covid has had on other services. How the recovery goes will shape the near future of work in health and social care. (Team leader Physiotherapist, female, 25-34)

This aligns very much with the observations made by Acermoglu and Johnson. In their study of the past 1000 years of human development. They observe that prosperity was not based on passive acceptance of technological progress but the challenging of choices regarding technology and work conditions[62].

Health care executive managers tend to take a more upbeat approach to application of technology to give more agency to health care workers:

The extent to which working patterns and working approaches have been revolutionised over the past fourteen/fifteen months, in particular so I think definitely for kind of office based staff there would be a real expectation that we have a kind of hybrid model of working. I think for direct care staff, I think that there is much more, there’s a more alert sense of the sort of digital and technology potential of changing patterns of care. So some of those things like, you know, NHS at home type models and remote access. And the extent to which the remote access is part of the workforce, challenges and solutions in a number of workplace areas, especially in areas like mental health, I think will be radically different. (Executive lead for strategy system development, male, 54-65)

As far as patients were concerned, there was however fear that the move towards digitalisation might increase inequalities. As one interviewee mentioned: it “may leave vulnerable people behind” (Physiotherapist ECPCT, female, 55-64). This reflects the literature mentioned earlier in this article on the difficulties for vulnerable persons to access online health services.

The future of place and health care delivery

Performative rhetoric was very much present in the language of the health managers interviewed in terms of transforming the place of work and the way of working. This might mean that these rhetorical techniques are used to persuade and mobilise in order to facilitate further organisational change. Here it is related to the changing role of the hospital which reflects what was already observed in our analysis of the secondary literature on changing the place of provision: that is moving care from the hospital to the community as both a financial and care imperative:

I think we need to accept that hospitals are really critically important when people are very very ill and when they need a bed and they need to be looked after in a very particular way but we’ve got to find a way of using things like wearable devices, technology, not assuming that everybody has to go to a central point for their care delivery, i.e. hospitals. (Chief Operating Officer, male, 45-54)

There is no doubt with the level of pressure over the last two years with Covid. I think we are going to need a vast array of new workers, a new workforce to come and support people in care homes and in their own homes. (Director of Commissioning, female, 45-54)

Changing the focus of curative care in hospitals to care in the communities was indeed very much present in the discourse:

I’d love it if we could develop social enterprise within localities, we could train people locally, we could employ people locally to really boost the economy which again has the biggest impact on health and let’s stop, let’s break down the barriers between the you know professional silos you know and have a holistic workforce that can work across and really really focus on the individual, the family and the preventative approach in getting in early. (Director of commissioning CCG, female 35-44)

Managerialist rhetoric is evident from the above discourses and often mirrors policy government proposals in the policy documents on the need to restructure the work place and the workforce (referring to new workers, co-production, redesigning social care, a holistic workforce…). Gahmberg[63] contended that the manager will use “metaphor management” in discourse to create a meaningful context for debate or as an attempt to instigate change in the workforce[64]. Many of the executive managers in the interviews do indeed seem to be pushing for new forms of work to integrate digital devices, work together across silos…Yet the frontline staff are underlining the threats for the future of an understaffed workforce who are ill-prepared for the future challenges of work.

Conclusions

The interviews conducted within the framework of this research project highlighted and confirmed a number of conclusions in the secondary literature related to difficulties in staff retention, underfunding, deprofessionalisation and the challenges to integrating digital technology in the work place. Much of the focus of future discourses on work in the health sector tends to be on improving skills or workforce adaptability. This may be considered as positive given the benefits of training and its ability to adapt the workforce to a new paradigm. However, in the same way as much of the technologically deterministic discourses, the managers contend that the workforce must adapt, otherwise the system becomes unsustainable. Managers are thus imposing the conditions for change through such performative discourses in a post-Covid era.

Managerial discourses also call for greater reliance on the third sector, voluntary and community based services, with the move away from hospital services and the general decline in public services. However, the secondary literature confirmed how resistance or the impractical nature of reducing hospital services will prevent a near future transformation of the health workplace setting and a move away from hospital services. The performative nature of the discourses of the executive managers in the empirical data is clear, with discourses directly connected to recommendations in government policy documents studied in the secondary literature, which propose further organisational change. In contrast, frontline staff demand greater recognition of occupational needs and deplore working conditions in these interviews which has again been reported in the wider literature on the subject. But within the interviews of the frontline staff, contradictory visions of the workplace are also displayed (one respondent contends that solutions are continually found to ensure high quality workers especially regarding the nursing profession, whilst another predicts the further decline of the profession).

The above analysis has also shown that there are some challenges which are very specific to the health care sector, namely workforce retention difficulties and the need for a greater number of workers in the health care sector to ensure future sustainability of health systems. However, the analysis of workers’ conditions and workplace changes has also served to highlight quite a number of work place challenges common to other sectors which would be worth exploring further. While the empirical evidence brings out some interesting trends in the sector, the analysis would need to be expanded by a larger number of interviews, or even more quantitative work, to confirm the findings especially those which diverge from the general literature on the subject.

—

NOTES

[1] DEPARTMENT FOR WORK AND PENSIONS, “Economic labour market status of individuals aged 50 and over, trends over time: September 2021”, DWP, 2021, https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/economic-labour-market-status-of-individuals-aged-50-and-over-trends-over-time-september-2021/economic-labour-market-status-of-individuals-aged-50-and-over-trends-over-time-september-2021.

[2] OECD, Health at a Glance, Paris: OECD, 2021, p. 18.

[3] Ruth LEVITT et al., op. cit.; P. LEONARD, op.cit.

[4] K. KRIPPENDORFF, Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology, Beverly Hills: Sage Publications, 1980.

[5] M. McKEE, et al., “The changing health needs of the UK population”, Health Policy, 397 (10288), May 2021, p. 1979-1991.

[6] Ibid.

[7] R. LEVITT et al., op. cit.; P. Leonard, op. cit.

[8] P. DOREY, “The Legacy of Thatcherism – Public Sector Reform”, Observatoire de la société britannique, 17, 2015, [DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/osb.1759].

[9] D. ALLEN, op. cit.

[10] S.A. BUETOW and M. ROLAND, “Clinical Governance: bridging the gap between managerial and clinical approaches to quality of care”, Quality in Health Care, 8, 1999, p. 184–190.

[11] P. LEONARD, op. cit.

[12] J. RIFKIN, The End of Work, NY, Putnam, 1995.

[13] HOUSE OF COMMONS (Health and Social Care Committee), “Workforce: recruitment, training and retention in health and social care”, Third Report of Session 2022–23, HC 115, 2023.

[14] NHS PROVIDERS is the membership organisation for the NHS hospital, mental health, community and ambulance services.

[15] NHS PROVIDERS, There for us: A better future for the NHS workforce, London: Foundation Trust Network, 2017.

[16] S. HIPPLE, “Worker displacement in the mid-1990’s”, Monthly Labor Review 122, 1999, p. 15-32; D. AUTOR, “The Polarization of Job Opportunities in the U.S. Labor Market: Implications for Employment and Earnings”, Center for American Progress and the Hamilton Project, 2010; M. GOOS, A. MANNING, and A. SALOMONS, “Explaining Job Polarization: The Roles of Technology, Offshoring, and Institutions”, University of Leuven, Center of Economic Studies Discussion Paper Series 11.34, 2011; M. GOOS, A. MANNING and A. SALOMONS, 2014. “Explaining Job Polarization: Routine-Biased Technological Change and Offshoring”, American Economic Review, American Economic Association, vol. 104(8), p. 2509-2526.

[17] NHS PROVIDERS, op. cit.

[18] British trade union and professional body for doctors and medical students.

[19] BMA, “NHS medical staffing data analysis”, BMA, March 2023, [https://www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/nhs-delivery-and-workforce/workforce/nhs-medical-staffing-data-analysis].

[20] NHS PROVIDERS, op.cit.

[21] M. CALNAN, D. WAINWRIGHT, M. FORSYTH and B. WALL, “Mental health and stress in the workplace: the case of general practice in the UK”, Social Science and Medicine 52, 2001, p. 499-507; J. FIRTH-CONZENS and R. PAYNE, Stress in health professionals, Chichester, Wiley, 1999; M. LINZER, J. McMURRAY, M. R. M. VISSER, F. J. OORT, E. SMETS and H. CJ DE HAES, “Sex differences in physician burnout in the United States and Netherlands”, Journal of the American Medical Women’s’ Association, 57, 2002, p. 191-193; U. ROUTH, C. L. COOPER and J. ROUTH, “Job stress among British general practitioners: predictors of job dissatisfaction and mental ill-health”, Stress Medicine 12, 1996, p. 155-166; J. SUNDQUIST and S. E. JOHANSSON, “High demand, low control, and impaired general health: Working conditions in a sample of Swedish general practitioners”, Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 28, 2000, p. 123-13, [PubMed: 10954139]; Y. UNCU, N. BAYRAM NAZAN, “Job related affective well-being among primary health care physicians”, European Journal of Public Health, 17, 2007, p. 514-519. [PubMed: 17185328].

[22] NHS PROVIDERS, op.cit.

[23] S. CROSSLEY, “Professionalism, de-professionalisation and austerity”, Social Work & Social Sciences Review 19(1), 2017, p. 3-6.

[24] S. CROSSLEY, op.cit.

[25] C. DAVIES, Gender and the Professional Predicament in Nursing, Buckingham: Open University Press, 1995; C. DAVIES, “Caregiving, Carework and Professional Care.” In Ann Brechin, Jan Walmsley, Jeanne Katz and Sheila Peace (Eds.), Care Matters: Concepts, Practice and Research in Health and Social Care, London, Sage, 1998; M. TRAYNOR et al., op. cit.

[26] D. ALLEN, op. cit.

[27] K. LAW and K. ARANDA, “The shifting foundations of nursing”, Nurse Education Today, 30, 2010, p. 544-547; M. TRAYNOR et al., op. cit.

[28] C. THORNELY, “A question of competence? Re-evaluating the roles of the nursing auxiliary and health care assistant in the NHS”, Journal of Clinical Nursing, 9, 2000, p. 451-458; M. TRAYNOR et al., op.cit.

[29] M. McKEE and L. LESSOF, “Nurse and doctor: whose task is it anyway?” In Jane Robinson, Alastair Gray and Ruth Elkan, (eds), Policy Issues in Nursing, Buckingham, Open University Press, 1992; P. LEONARD, op. cit.

[30] M. ANDERSON, et al., “Securing a sustainable and fit-for-purpose UK health and care workforce”? Lancet, 397, 2021, May, p. 1992-2011, [https://doi.org/10.1016/ S0140-6736(21)00231-2].

[31] Ibid.

[32] WORLD HEALTH ORGANISATION, The World Health Report: 2006. Working Together for Health, Geneva, World Health Organization; 2006; ILO (Ungureanu, Marius, Wiskow, Christiane and Santini, Delphine.), “The future of work in the health sector,” ILO Working Papers 995016293502676, International Labour Organization, 2019; WORLD HEALTH ORGANISATION, State of The World Nursing 2020: Investing in Education, Jobs and Leadership, GENEVA: World Health Organization, 2020; HOUSE OF COMMONS, 2023, op. cit.

[33] ILO, op. cit.

[34] Non-standard forms of employment

[35] Ibid.

[36] L. DALINGWATER, The NHS and Contemporary Health Challenges from a Multilevel Perspective, Hershey, IGI Global, 2020.

[37] EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, “The rise of digital health technologies during the pandemic”, European Parliament Briefing, 2021.

[38] Ibid.

[39] L. FERNANDES, M. Eb FITZPATRICK, M. ROYCROFT, “The role of the future physician: building on shifting sands” Clin Med (Lond). 20(3), April 2020, p. 285-9, [DOI: 10.7861/clinmed.2020-0030].

[40] Ibid.

[41] DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND SOCIAL CARE, Foreword by Sajid Javid, Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. Policy Paper, A plan for digital health and social care, 2022, [https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/a-plan-for-digital-health-and-social-care/a-plan-for-digital-health-and-social-care].

[42] HOUSE OF LORDS, op. cit

[43] W. FRUELWIRT and P. DUCKWORTH, “Towards better healthcare: What could and should be automated?” Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 172, 2021, [DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120967].

[44] BMA, Building the Future: Getting IT Right: The case for urgent investment in safe, modern technology and data sharing in the UK’s health services, London, BMA, 2022.

[45] ILO, op. cit.

[46] E. STONE, “Digital exclusion & health inequalities”, Good Things Foundation, 2021, [https://www.goodthingsfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Good-Things-Foundation-2021-%E2%80%93-Digital-Exclusion-and-Health-Inequalities-Briefing-Paper.pdf].

[47] S. J. YATES, E. CARMI, E. LOCKLEY, A. PAWKLUCZUK, T. FRENCH and S. VINCENT, “Who are the limited users of digital systems and media? An examination of UK evidence”, First Monday 25(6), 6 July 2020, [https://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/10847].

[48] Ibid.

[49] H. HOLMES and G. BURGESS, “Digital exclusion and poverty in the UK: How structural inequality shapes experiences of getting online”, Digital Geography and Society 3, 2022; E. J. HELPSER “A corresponding fields model for the links between social and digital exclusion”, Communication Theory? 22 (4), 2012, p. 403-426; P. A. LONGLEY and A. D. SINGLETON, “Linking social deprivation and digital exclusion in England”, Urban Studies 46 (7), 2009, p.1275-1298.

[50] N. GASTEIGHER, S. N. VAN DER VEER, P. WILSON and D. DOWDING, “Upskilling health and care workers with augmented and virtual reality: protocol for a realist review to develop an evidence-informed programme theory”, BMJ Open, 5 Juk2021,11(7), [DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050033].

[51] Ibid.

[52] DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND SOCIAL CARE, op. cit.

[53] L. PHILLIPS and I. SUZAN, “Capacity-Building: The Neoliberal Governance of Development”, Canadian Journal of Development Studies / Revue canadienne d’études du développement, 25(3), p. 393-409, [DOI: 10.1080/02255189.2004.9668985].

[54] DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND SOCIAL CARE, op. cit.

[55] M. K. WALSH, “The future of hospitals”, Aust Health Rev. 25(5), 2002, p. 32-44, [DOI: 10.1071/ah020032a. PMID: 12474500, p. 32].

[56] Ibid, p. 33.

[57] Ibid.

[58] M. HENSCHER, N. EDWARDS and R. STOKES, “International Trends in the provision and utilisation of hospital care”, BMJ, 319, 1999, p. 845-8; M. HENSCHER and N. EDWARDS, “Hospital provision, activity and productivity in England since the 1980’s”, BMJ, 319, 1999, p. 911-4; J. POSNETT, “Is bigger better; concentration in the provision of secondary care”, BMJ 319, 1999, p. 1063-5; R. DOWIE and M. LANGMAN, “Staffing of hospitals: future needs, future provision”, BMJ, 319, 1999, p. 1193-5; J. HAYCOCK, A. STANLEY, N. EDWARDS and R. NICHOLLS, “The hospital of the future: changing hospitals” BMJ, 319, 1999, p. 1262-4.

[59] J. HAYCOCK et al., op. cit., p. 1262

[60] L. JONES and J. GREEN, “Shifting discourses of professionalism: A case study of general practitioners in the United Kingdom, Sociology of Health & Illness, 28(7), ISSN 0141– 9889, 2006: 927 – 950, [DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2006.00513.xB].

[61] S. ZUBOFF, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power, New York, Public Affairs, 2019.

[62] D ACEMOGLU and Simon JOHNS, Power and Progress: Our Thousand Year Struggle Over Technology and Prosperity, John Murray Press, 2023.

[63] H. GAHMBERG, “Chapter 10. Metaphor Management: On the Semiotics of Strategic Leadership”, In Barry Turner (ed.) Organizational Symbolism, De Gruyter, 1990.

[64] J. M. SWALES and P. S. ROGERS, “Discourse and the Projection of Corporate Culture: The Mission Statement. Discourse & Society” 6.2, 1995, p. 223-242.

Bibliographie

ACEMOGLU, Daron and Simon Johns, Power and Progress: Our Thousand Year Struggle Over Technology and Prosperity, John Murray Press, 2023.

ALLEN, Davina, The Changing Shape of Nursing Practice, London: Routledge, 2001.

ANDERSON, Michael, Ciaran O’NEILL, Jill MACLEOD, Andrew CLARK, Michael WOODS, Charlotte JOHNSTON-WEBBER, Anita CHARLESWORTH, Moira WHYTE, Margaret FOSTER, Azeem MAJEED, Emma PITCHFORTH , Elias MOSSIALOS, Miqdad ASARIA and Alistair McGUIRE, “Securing a sustainable and fit-for-purpose UK health and care workforce”, Lancet, 397, 2021, May, p. 1992-2011, [https://doi.org/10.1016/ S0140-6736(21)00231-2].

AUTOR, David, H., “The Polarization of Job Opportunities in the U.S. Labor Market: Implications for Employment and Earnings”, Center for American Progress and the Hamilton Project, 2010.

BMA, “NHS medical staffing data analysis”, BMA, March 2023, [https://www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/nhs-delivery-and-workforce/workforce/nhs-medical-staffing-data-analysis].

BMA, Building the Future: Getting IT Right: The Case for Urgent Investment in Safe, Modern Technology and Data Sharing in the UK’s Health Services, London, BMA, 2022.

BUETOW, Stephen, A. and Martin Roland, “Clinical Governance: bridging the gap between managerial and clinical approaches to quality of care”, Quality in Health Care, 8, 1999, p. 184-190.

CALNAN, Michael, David WAINWRIGHT, Malcolm FORSYTH and Barbara WALL, “Mental health and stress in the workplace: the case of general practice in the UK”, Social Science and Medicine, 52, 2001, p. 499-507.

CROSSLEY, Stephen, “Professionalism, de-professionalisation and austerity”, Social Work & Social Sciences Review, 19(1), 2017, p. 3-6.

DALINGWATER, Louise, The NHS and Contemporary Health Challenges from a Multilevel Perspective, Hershey, IGI Global, 2020.

DAVIES, Celia, Gender and the Professional Predicament in Nursing, Buckingham, Open University Press, 1995.

DAVIES, Celia “Caregiving, Carework and Professional Care”, In Ann Brechin, Jan Walmsley, Jeanne Katz and Sheila Peace (Eds.), Care Matters: Concepts, Practice and Research in Health and Social Care, London, Sage, 1998

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND SOCIAL CARE, Foreword by Sajid Javid, Secretary of State for Health and Social Care, Policy Paper: A plan for digital health and social care, 2022, [https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/a-plan-for-digital-health-and-social-care/a-plan-for-digital-health-and-social-care].

DEPARTMENT FOR WORK AND PENSIONS, “Economic labour market status of individuals aged 50 and over, trends over time”, September 2021, DWP, [https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/economic-labour-market-status-of-individuals-aged-50-and-over-trends-over-time-september-2021/economic-labour-market-status-of-individuals-aged-50-and-over-trends-over-time-september-2021].

DOREY, Peter, “The Legacy of Thatcherism – Public Sector Reform”, Observatoire de la société britannique, 17, 2015, [DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/osb.1759].

DOWIE, Robin and Michael LANGMAN, “Staffing of hospitals: future needs, future provision”, BMJ, 319, 1999, p. 1193-5.

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, “The rise of digital health technologies during the pandemic”, European Parliament Briefing, 2021.

FERNANDES, Linford, Michael Eb FITZPATRICK and Matthew ROYCROFT, “The role of the future physician: building on shifting sands”, Clin Med (Lond). 20(3), April 2020, p. 285-9, [DOI: 10.7861/clinmed.2020-0030].

FIRTH-CONZENS, Jenny and Roy PAYNE, Stress in health professionals, Chichester, Wiley; 1999.

FRUELWIRT, Wolfgang and Paul DUCKWORTH, “Towards better healthcare: What could and should be automated?”, Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 172, 2021, [DOI https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120967].

GASTEIGHER, Norina, Sabine N. VAN DER VEER, Paul WILSON and Dawn DOWDING, “Upskilling health and care workers with augmented and virtual reality: protocol for a realist review to develop an evidence-informed programme theory”, BMJ Open, 5 Jul 2021, 11(7), [DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050033].

GAHMBERG, Henrik, “Chapter 10. Metaphor Management: On the Semiotics of Strategic Leadership”, in Barry Turner (ed.) Organizational Symbolism, De Gruyter,1990.

GOOS, Maarteen, Alan MANNING, and Anna SALOMONS. “Explaining Job Polarization: The Roles of Technology, Offshoring, and Institutions”, University of Leuven, Center of Economic Studies Discussion Paper Series, 11.34, 2011.

GOOS, Maarten, Alan MANNING & Anna SALOMONS, “Explaining Job Polarization: Routine-Biased Technological Change and Offshoring”, American Economic Review, American Economic Association, vol. 104(8), 2014, p. 2509-2526.

HAYCOCK, Jane, Anna STANLEY, Nigel EDWARDS and Robert NICHOLLS, “The hospital of the future: changing hospitals”, BMJ, 319, 1999, p. 1262-4.

HELPSER, Ellen, J., “A corresponding fields model for the links between social and digital exclusion”, Communication Theory, 22 (4), 2012, p. 403-426, [DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2012.01416.x].

HENSCHER, Martin, Nigel EDWARDS and Rachel STOKES, “International Trends in the provision and utilisation of hospital care”, BMJ, 319, 1999, p. 845-8.

HENSCHER, Martin and Nigel EDWARDS, “Hospital provision, activity and productivity in England since the 1980’s”, BMJ, 319, 1999, p. 911-4.

HENSCHER, Martin, Naomi FULOP, Joanna COAST and Emma JEFFREYS, “Better out than in? Alternatives to acute hospital care”, BMJ, 319, 1999, p. 1127-30.

HIPPLE, Steven, “Worker displacement in the mid-1990’s”, Monthly Labor Review, 122, 1999, p. 15-32.

HOLMES, Hannah and Gemma BURGESS, “Digital exclusion and poverty in the UK: How structural inequality shapes experiences of getting online”, Digital Geography and Society 3, 2022.

HOUSE OF COMMONS (Health and Social Care Committee), “Workforce: recruitment, training and retention in health and social care”, Third Report of Session 2022–23, HC 115, 2023.

HOUSE OF LORDS (Public Services Committee), 1st Report, Fit for the future? Rethinking the public services workforce, 2. Oral and written evidence, 19th July 2022, HL 48 Public Services Committee, ISBN: 9781804936665.

ILO (Ungureanu, Marius. & Wiskow, Christiane. & Santini, Delphine), “The future of work in the health sector,” ILO Working Papers, n°995016293502676, International Labour Organization, 2019.

JONES, Lorelei and Judith GREEN, “Shifting discourses of professionalism: A case study of general practitioners in the United Kingdom, Sociology of Health & Illness, 28( 7), ISSN 0141– 9889, 2006: 927-950, [DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2006.00513.xB].

KRIPPENDORF, Klaus, Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology, Beverly Hills, Sage Publications, 1980.

LAW, Kate and Kay ARANDA, “The shifting foundations of nursing”, Nurse Education Today, 30, 2010, p. 544-547.

LEONARD Pauline, “Playing’ Doctors and Nurses? Competing Discourses of Gender, Power and Identity in the British National Health Service” The Sociological Review, 51(2), 2003, p. 218-237. [DOI:10.1111/1467-954X.00416].

LEVITT, Ruth, Andrew Wall and John Appleby, The Reorganized National Health Service (sixth edition), Cheltenham, Stanley Thornes, 1999.

LINZER Mark, Julia McMURRAY. E, Mechteld René Maria VISSER, Frans J. OORT, Ellen SMETS and Hanneke CJ de HAES, “Sex differences in physician burnout in the United States and Netherlands.” Journal of the American Medical Womens’ Association , 57, 2002, p. 191-193.

LONGLEY, Paul, A and Alexander D. SINGLETON”, Linking social deprivation and digital exclusion in England”, Urban Studies, 46 (7), 2009, p. 1275-1298, [DOI:10.1177/0042098009104566].

McKEE, Martin and Leila LESSOF, “Nurse and doctor: whose task is it anyway?” In Jane Robinson, Alastair Gray and Ruth Elkan, (eds), Policy Issues in Nursing, Buckingham, Open University Press, 1992?

McKEE, Martin, Karen Dunnell, Michael Anderson, Carol Brayne, Anita Charlesworth, Charlotte Johnston-Webber, Martin Knapp, Alistair McGuire, John N. Newton, David Taylor and Richard G Watt, “The changing health needs of the UK population” Health Policy, 397 (10288), May 2021, p. 1979-1991.

NHS PROVIDERS, There for us: A better future for the NHS workforce, London: Foundation Trust Network, 2017.

OECD, Health at a Glance, Paris: OECD, 2021.

PHILLIPS, Lynne and Ilcan SUZAN, “Capacity-Building: The Neoliberal Governance of Development”, Canadian Journal of Development Studies / Revue canadienne d’études du développement, 25(3), p. 393-409, [DOI: 10.1080/02255189.2004.9668985].

POSNETT John, “Is bigger better; concentration in the provision of secondary care”, BMJ 319, 1999, p. 1063-5.

RIFKIN, Jeremy, The End of Work, NY, Putnam, 1995.

ROUTH, Usha, Cary L. COOPER and Jaya ROUTH, “Job stress among British general practitioners: predictors of job dissatisfaction and mental ill-health”, Stress Medicine, 12, 1996, p. 155-166.

SUNDQUIST, Jan and Sven E. JOHANSSON, “High demand, low control, and impaired general health: Working conditions in a sample of Swedish general practitioners”, Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 28, 2000, p.123-131, [PubMed: 10954139].

STATISTICA, “NHS Staff Shortages”, November 2023, [https://www.statista.com/topics/9575/nhs-staff-shortage/].

STONE, Emma, “Digital exclusion & health inequalities”, Good Things Foundation, 2021, [https://www.goodthingsfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Good-Things-Foundation-2021-%E2%80%93-Digital-Exclusion-and-Health-Inequalities-Briefing-Paper.pdf].

SWALES, John M. and Priscilla S. Rogers, “Discourse and the Projection of Corporate Culture: The Mission Statement. Discourse & Society” 6.2, 1995, p. 223-242.

THORNELY, Carole, “A question of competence? Re-evaluating the roles of the nursing auxiliary and health care assistant in the NHS”, Journal of Clinical Nursing, 9, 2000, p. 451-458.

TRAYNOR, Michael, Nina NISSEN, Carol. LINCOLN, Niels BUUSB, “Occupational closure in nursing work reconsidered: UK health care support workers and assistant practitioners: A focus group study”, Social Science & Medicine, 136–137, July 2015, p. 81-88.

UNCU Yesmin, Nuran BAYRAM NAZAN, “Job related affective well-being among primary health care physicians”, European Journal of Public Health, 17, 2007, p. 514-519, [PubMed: 17185328].

WALSH, Michael, K. “The future of hospitals”, Aust Health Rev. 25(5), 2002, p. 32-44, [DOI: 10.1071/ah020032a].

WORLD HEALTH ORGANISATION, The World Health Report: 2006. Working Together for Health, Geneva, World Health Organization, 2006.

WORLD HEALTH ORGANISATION, State of The World Nursing 2020: Investing in Education, Jobs and Leadership, GENEVA, World Health Organization, 2020.

WILKINSON, Emma, UK NHS staff: stressed, exhausted, burnt out, The Lancet, 385 (9971), 7 March 2015, p. 841-842.

YATES, Simeon, John KIRBY and Eleanor LOCKLEY, “Digital media use: Differences and inequalities in relation to class and age”, Sociological Research, 20 (4), 2015, p. 1-21, [DOI: 10.5153/sro.3751].

YATES, Simeon J., Elinor CARMI, Eleanor LOCKLEY, Alicja PAWKLUCZUK, Tom FRENCH and Stéphanie VINCENT, “Who are the limited users of digital systems and media? An examination of UK evidence”, First Monday, 25(6), 6 July 2020, [https://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/10847]

ZUBOFF, Shoshana, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power, New York, Public Affairs, 2019.

Auteurs

Louise DALINGWATER

Sorbonne Université, Histoire et dynamique des espaces anglophone (HDEA), EA 4086

louise.dalingwater @ sorbonne-universite.fr

Références

Pour citer cet article :

Louise DALINGWATER - "Louise DALINGWATER, Giving Voice to the Workers: Healthcare Challenges on the Frontline in Britain" RILEA | 2023, mis en ligne le 14/12/2023. URL : https://anlea.org/revues_rilea/louise-dalingwater-giving-voice-to-the-workers-healthcare-challenges-on-the-frontline-in-britain/