Résumé

Le commerce électronique peut-il relancer l’économie irlandaise après le Brexit et la pandémie ?

Résumé

En 2020 et 2021, la République d’Irlande a connu plusieurs crises économiques, qui ont moins touché les multinationales implantées en Irlande que les entreprises locales. Ces dernières ont été impactées par les restrictions de déplacement et elles n’étaient pas équipées pour bénéficier du développement du commerce électronique. En effet, alors qu’entre 2017 et 2019, les revenus du commerce électronique en République d’Irlande avaient augmenté de 32 % par an, en 2020, en pleine crise de la Covid-19, le commerce en ligne a augmenté de 159 %. De plus, les surcoûts, retards et tracasseries administratives causées par le Brexit sur le flux de marchandises entre la République d’Irlande et le Royaume-Uni pourraient également permettre également aux détaillants irlandais de se démarquer. Peut-il s’agir du déclencheur dont les entreprises irlandaises avaient besoin pour saisir l’opportunité que représente le commerce en ligne ?

Mots-clés : Irlande (République), e-commerce, Brexit, Covid 19, internet

Abstract

In 2020 and 2021, the Republic of Ireland experienced several economic crises, which affected multinationals based in Ireland less than local companies. Irish SMEs were affected to a greater exente by travel restrictions and were not equipped to benefit from the development of e-commerce. Indeed, while between 2017 and 2019, e-commerce revenues in the Republic of Ireland grew by 32% per year, in 2020, in the midst of the Covid-19 crisis, online commerce grew by 159%. In addition, the extra costs, delays and red tape caused by Brexit on the flow of goods between the Republic of Ireland and the UK could also benefit Irish retailers. Could this be the trigger Irish SMEs needed to seize the opportunity presented by online commerce?

Keywords: Ireland (Republic), online trade, Brexit, Covid-19, internet

Texte

The COVID-19 pandemic caused major disruptions in the world in 2020 and 2021. According to a study carried out by Oxford University between 2020 and 2021, the Republic of Ireland was the third European country to have adopted the most stringent restrictions, partly due to an Irish health system on the verge of collapse.[1] The Irish, for example, endured months of isolation with three long lockdowns in the Republic of Ireland (between 24 March 2020 and 8 June 2020, then between 15 October 2020 and 1 December 2020, and finally between 24 December 2020 and 17 May 2021). Consequently, the country was put at a standstill: schools and universities were closed, students had to attend online classes, shops closed, businesses switched to remote working, some even closed, and unemployment soared during these two years.

Additionally, over these two years, the Irish economy was hit by a series of worldwide crises. First, on 1 February 2020, Ireland faced the exit of its main economic partner, the United Kingdom, from the European Union (Brexit). From 1 January 2021, the application of the Northern Ireland Protocol created a significant number of uncertainties for Irish companies, even though they benefited from financial support mechanisms implemented by the Irish government (notably via credits from the Brexit Adjustment Reserve). The Windsor Framework which came into effect on 25 March 2023 simplified the customs procedures for goods imported to Northern Ireland. Secondly, the outbreak of COVID-19 and the global emergency measures implemented to halt its proliferation disrupted international supply chains, already crippled by Brexit. The Irish economy suffered a severe shock: in the second quarter of 2020, its GNP was down 7.4 %.[2] The drop was almost as severe as the one of the 2008 financial crisis, when in the first quarter of 2009, Irish GNP fell by 12 %.[3] Finally, the recovery was hampered by the consequences of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and the rise of inflation.

Nonetheless, according to international indicators, the Irish economy proved to be resilient along those two years as Ireland had enviable growth rates: 5.9 % for GDP and 3.4 % for GNP in 2020,[4] while European economies were sinking (-4.6 % for Germany, -7.9 % for France and -9.3 % for the UK in 2020).[5] By 2021, Ireland was growing strongly (+13.6 % for GDP and +14.7 % for GNP) while European economies were stagnating (Germany +1.1 %, the UK +1.7 % and France +1.1 %).[6] However, those strong GNP figures conceal a two-speed economy in the Republic of Ireland. On the one hand, the sectors dominated by multinationals, those notably in information and communication technologies (ICT) and in pharmaceutical, medical and chemical products (including vaccine production for Europe), showed remarkable dynamism and continued to increase their weight in the national economy in terms of jobs, exports and production during this period.[7] On the other hand, during the repeated lockdowns, Irish businesses, which are mainly Irish-owned SMEs serving the domestic market, suffered a drop in demand.[8] In 2020, the companies which were in close contact with the public such as those operating in the hotel, catering and transport sectors, as well as those in the entertainment and leisure sectors, nearly collapsed.

Crises usually accelerate transitions, but can we say that this is true for Ireland after the COVID crisis? In order to answer this question, the article raises the following issues: to what extent has COVID-19 accelerated the adoption of e-commerce in Ireland? What changes do Irish companies have to perform to adjust to post-COVID retail? Is this a long-term opportunity for Irish-owned companies?

A growing digital economy: online sales during the pandemic

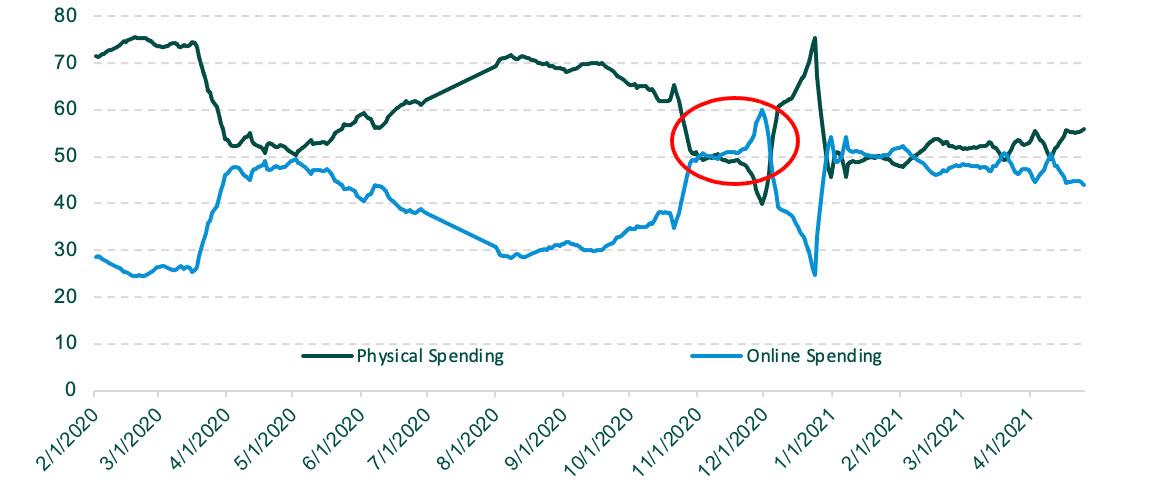

During the pandemic, according to a study by Wolfgangdigital based on a sample of online transactions, e-commerce revenues in the Republic of Ireland grew by 159% in 2020 compared to an annual growth of only 32% between 2017 and 2019.[9] Online sales even outperformed brick-and-mortar sales in November 2020, as can be seen in this graph showing the share of spending using debit cards for online transactions according to consumer data provided by financial technology company Revolut.

Graph 1 – Proportion of debit card spending spent online and physically (dates are presented month/day/year)

Source: From Revolut et Department of Finance calculations. GOVERNMENT OF IRELAND, Economic recovery Plan 2021, Accompanying Background Paper: Accelerating Trends and Shifts, 2021, p. 7.

The increase in online sales started in March 2020 which matched the first series of restrictions to limit the spread of the virus. On 12 March 2020, the Taoiseach, Irish Prime Minister Leo Varadkar, announced the closure of schools and nurseries. Initially, shops remained open, but three days later, on 15 March 2020, pubs and bars closed. Finally, on 24 March 2020, the Taoiseach announced the enforcement of a strict lockdown, closing all non-essential shops. During that month, online sales increased to just under 50% of credit card purchases in Ireland,[10] but it did not manage to offset the decline in sales in physical shops, with total sales down 27% at the end of March compared to the first week of March.[11] Online sales remained high, but declined throughout the first lockdown, which ended on 8 June 2020. After a small peak in June 2020, online sales slightly increased again from August 2020 compared to physical card purchases when the number of COVID-19 cases rose in counties Laois, Offaly and Kildare and new restrictions were put in place, first locally and then nationally in September 2020. At the beginning of October 2020, with rumours of a new lockdown soon in place, the Irish rushed to the shops to stock products up and do their Christmas shopping, which explains the slight peak in brick-and-mortar purchases at this period. In November 2020, for the first time, the share of online transactions using bankcards exceeded physical purchases, as shown by the red circle on graph 1. It declined in December 2020 as the Irish government tried to ease restrictions, but rose again at the end of December 2020 with the setting up of a new lockdown on Christmas Eve. Online sales remained high for the first half of 2021 with 57% in January, compared to a monthly average of 39% in 2019 as Ireland remained in lockdown during this period. Although restrictions remained unchanged until the beginning of May, the proportion of in-store spending rose steadily to almost 49% at the end of April 2021.[12] This reflects the growing adaptability of businesses, but above all a greater level of consumer mobility and a change in buying behaviour patterns when the opportunity to consume in person presented itself again with the reopening of non-essential retail outlets on 10 and 17 May 2021 (10 May 2021: click and collect and shops could open by appointment, full reopening on 17 May 2021). After those dates, in-store spending rose sharply. By the end of July 2021, in-person payments accounted for almost 60% of spending, compared with 49% in April 2021.[13]

Irish companies need to adapt to e-commerce

Before the pandemic, according to a study carried out by the organisation in charge of registering Irish domain names (.ie), Irish consumers regularly shopped online: 82% of those questioned said they shopped online at least from time to time.[14] However, those online consumers would buy from international sites which were better perceived due to their lower prices, wider product ranges and more intuitive and better designed marketplaces and websites.[15] Indeed, in many sectors, prior to the pandemic, international companies were the only ones to offer online shopping.

The shift to the digital age has raised consumer expectations. Online shoppers now want Irish websites to offer the same level of services and convenience as international marketplaces. E-commerce starts with an online presence. To be visible, Irish small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) need to have a website or a page on social networks, preferably both. Two-thirds of Irish-owned SMEs (66%) in the retail and customer-facing professional services sector have a website. More than three quarters (76%) of businesses with more than six employees even have a website.[16] Before the pandemic, although online spending was already the norm among Irish consumers, only 25% of Irish SMEs sold products online. Within two years, Irish SMEs adapted. Between March 2020 and March 2021, domain registrations with the .IE domain registry increased by 40%.[17] Many Irish companies improved their online presence to somewhat alleviate the impact of lockdowns.[18] However, the surge was short-lived as in 2022, new .ie domain registrations[19] dropped by 22.6 % compared to 2021 and moved back to pre-pandemic levels. As .IE explained: “the mass digital mobilization of 2020 and 2021 has tapered off”.[20]

When the virus appeared in February 2020, Irish businesses were not very committed to digital markets. The Irish government therefore offered a number of financial incentives to help businesses trade online depending on their size and their online presence. The aim of the support was clearly to limit business failures and job losses in order to minimise periods of unemployment, reduce investment and lower household incomes.[21]

Firstly, the Irish authorities developed the ‘Covid-19 Online Retail Scheme’ to help local retail businesses improve their online presence. During the pandemic, three calls were introduced to help Irish businesses to achieve a step change in online capability. Only businesses with more than 10 employees that were already selling online before COVID-19 could apply. According to Enterprise Ireland, Ireland’s business development agency, the aim was, and still is, to develop a more competitive online presence that would enable Irish businesses to increase their sales and to improve their competitiveness and resilience in the domestic and global marketplace, both online and offline.[22] To benefit from this support, businesses had to have a physical shop, employ at least 10 full-time staff, have the potential to maintain or create jobs, generate growth in online transactions, and the ambition to internationalise their business. Some businesses selected for the first time were awarded funding covering up to 80% of project costs, whereas businesses that had already benefited from this programme only received a grant covering 50% of the project, with a maximum amount of €40,000.[23] In the first half of 2021, more than two-thirds of the companies applying for grants were outside Dublin.[24]

For micro-businesses or those that did not have an online presence yet, the ‘Trading Online Voucher Scheme’, which offers grants to create an online presence, was also generously improved. The scheme, which was launched in 2013 when only a quarter of Irish small businesses were trading online, is aimed at micro-businesses[25] with little or no e-commerce activity. Micro-businesses are eligible for a grant of up to €5,000. The programme also makes it easier to subscribe to low-cost online sales platform solutions in order to quickly establish an online commercial presence. During the pandemic, the government allowed businesses that had already successfully used a €5,000 grant from this programme to apply again. Údarás na Gaeltachta, a state agency in charge of developing the Irish-speaking regions of Ireland (particularly in the west of Ireland), was also offering an additional €2,500 for businesses in areas where Irish is spoken. It was a great success as in the space of three months in 2020, the Irish authorities received as many applications as in the three years preceding the pandemic.[26] Ministers Humphreys and Bruton stated:

Údarás na Gaeltachta client companies have demonstrated a particular willingness to innovate in order to survive the current pandemic and a move towards online trading is just one of the ways in which this openness to innovation has manifested itself.[27]

The budget for this aid was increased tenfold to reach €20 million in 2020.[28] In addition, the Irish authorities also provided training for employees to develop their digital skills (particularly in e-marketing) through the ‘Future Jobs Ireland’, ‘Springboard+’, ‘Skillnet Ireland’ and ‘SOLAS Skills to Advance’ programmes.[29]

Lastly, Ireland stepped up its broadband programme to improve coverage in rural areas. In 2019, the proportion of Irish households with broadband access (fixed and mobile) was 90%, compared with an EU average of 88%, but in the same year, 20% of households in the border counties (with Northern Ireland) and 10% of those in the West of Ireland said broadband was not available, and 25% of respondents in rural areas said they had daily problems with the quality of mobile phone coverage. The situation was no better for businesses: a quarter of them said that a broadband connection was not available in their area. In total, 8% of the 1,000 businesses surveyed by .IE Domain Registry said that their main obstacle to doing more business online was poor broadband connectivity.[30]

Long-term implications

COVID-19 boosted the development of online retailing in Ireland: by 2020, online retailing had reached estimates for 2024, small businesses that would never have taken the plunge did so, and, finally, people who would probably never have bought online were forced to do so. For example, the over-65s who have the highest purchasing power in Ireland,[31] were also the least likely to shop online, but because of the pandemic they learned to do so. A blog on e-commerce in Ireland reported that they are now snapping up delivery slots for groceries ordered from supermarket websites.[32] Does this mean that e-commerce will continue on this trajectory in the years to come? And if e-commerce is flourishing in Ireland, who will really benefit from it? Local brands and Irish SMEs or major international online retailers?

International companies used to dominate online consumer spending. For example, the top three online retailers in Ireland in 2021 were Amazon (USA), Tesco (UK) and Argos (UK) and together they took 25 % of Ireland’s e-commerce revenue. They were followed by three clothing retailers (Next (UK), ASOS (UK) and Zara (Spain)).[33] Ireland is therefore marked by high levels of cross-border shopping. Unfortunately, the Irish retail giant Penneys (Primark in the UK) does not sell online. But, during the lockdowns, Irish customers bought slightly more from domestic companies: 53% of their online purchases were made from domestic companies, compared with 48% previously. This change is limited and we might wonder whether it could just be explained by the willingness or solidarity of the Irish to help their domestic SMEs. According to the .IE We are Ireland online survey: “More than two thirds (67%) of consumers who made most of their online purchases from Irish businesses explicitly stated that they wanted to help Irish SMEs through the crisis.” [34] Was it just a question of practicality and fast delivery? COVID-19 and Brexit created disruptions in supply chains. As deliveries in Ireland from Britain and Europe took longer, Irish customers had perhaps decided to buy more from domestic retailers to get the products they wanted faster.

This raises legitimate questions about the behaviour of the Irish once life returns to normal. Pulitzer Prize-winning author Charles Duhigg states in his book The Power of Habit that 40% of what we do each day is done on ‘autopilot’. In her 2009 study on habit formation, Phillippa Lally found that new habits take on average 66 days to become established.[35] After two years of COVID-19 and 227 cumulative days of lockdown in Ireland, the ways in which people work, communicate, entertain themselves and shop have all been radically and permanently altered.

Despite the possible creation of a habit to buy more Irish, the commitment of retail patriotism is open to question when we look at the surveys. When COVID-19 appeared in 2020, there was a patriotic surge with 53 % of Irish customers buying products from Irish SMEs. But, in 2021 there was a slight decrease as 49% of online sales were with Irish SMEs. In 2022, customers swung back to Irish businesses with 55% of online purchases being domestic. Therefore, the trend is not clear and we will have to analyse Irish purchases over the next years to see which trend emerges

Before the pandemic, the Irish ordered a lot of products from British retailers, as they did not have equivalent sites in Ireland (Argos, ASOS, Next). The geographical, cultural and linguistic proximity of the British sites made them attractive and easy to use. Now that the UK has left the EU, products imported from the UK have become less attractive for several reasons. First, imported products from the UK are subject to taxes and charges that can raise their cost by up to 40%. Secondly, the delivery times have also increased due to administrative and customs formalities. Thirdly, Great Britain experienced slightly higher inflation rates than Ireland over the last three years (see Table 1).

Table 1 – Inflation in Ireland and the UK, Percentage change over 12 months for consumer Price index, % (2020-2023)

| August 2020 | January 2021 | July 2021 | January 2022 | July 2022 | January 2023 | July 2023 | |

| Ireland | -1% | -0,2% | 2,2% | 5% | 9,1% | 7,8% | 5,8% |

| UK | 0,2% | 0,7% | 2% | 5,5% | 10,1% | 10,1% | 6,8% |

Source: Central statistics Office, “CPM01 – Consumer Price Index”, 9 Nov. 2023, https://data.cso.ie/, Office for National Statistics, “Consumer price inflation tables”, 18 October 2023, https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/inflationandpriceindices/datasets/consumerprice inflation

The Irish may therefore continue to buy more products from Irish sites than from international ones, applying the same strategy as Irish companies that, in the face of Brexit, have sought out other suppliers, either foreign / non-UK ones (22%) or Irish ones (21%).[36] They might also start using non-UK European sites if the delivery options are acceptable for them.

After delivering the Irish market from its British fulfilment centres, Amazon decided to mitigate its supply chain disruptions by opening its first fulfilment centre west of Dublin in Baldonnell, which enabled the multinational to bypass extra shipping charges and logistics delays that were brought on by Brexit (up to 50 per cent) in September 2022.[37] However, so far, Amazon has shown no intention of having an Ireland-specific website. Irish customers need to log on the British website and pay in sterling or on the German website and use euros (but with extra delivery charges).[38] Irish companies, both manufacturers and distributors, could join Amazon’s online sales platform, taking advantage of its marketplace and logistics system for deliveries and returns. In 2022, there were around 1,200 small sellers who were operating through Amazon.[39] But the arrival of such an online giant on the Irish market with a one-day delivery could also close the online window of opportunity for Irish SMEs that managed to capture Irish customers during COVID-19. As Amazon employed around 5,000 people in Ireland in 2023, some Irish customers might also think they are buying from an ‘Irish company’. Some studies show that, in the long run, the arrival of the e-commerce giant may result in a net destruction of jobs, ultimately harming local retail businesses, which were already weakened by the pandemic.[40]

As competition intensifies and as Irish SMEs are unlikely to compete with such multinationals on price, product range and affordability, they may bet on their USPs (Unique Selling Propositions) to ensure long-term survival and prosperity: according to a survey from .IE, native SMEs are considered more trustworthy and reliable, their delivery options are faster and more sustainable and their customer service better.[41] Moreover, SMEs should take note of what consumers truly value. For example, they might consider an omnichannel approach for consumers where their shopping needs are met by a combination of traditional high street and online shopping. Likewise, following the example of hybrid working with some days worked in the office and others from home, hybrid shopping is gathering pace. Customers enjoy the convenience of in-store shopping while simultaneously appreciating the ease and speed of e-commerce such as ordering online and picking up the parcel in a shop, ordering online to cook at home, browsing at home to buy in a shop. Irish SMEs that are flexible enough to facilitate both types of sales will attract more customers and be in a better position to compete with international retailers. Moreover, for some omnichannel businesses, online shopping may become their flagship shop, generating more revenue in their virtual cash register than in their physical shop. Nevertheless, according to .IE, “just 10% of the SMEs we surveyed regard the fuller integration of their physical shop with their online premises and vice versa, as a priority digital investment area over the next five years.”[42]

These changes also have implications for Irish towns and urban areas due to footfall reduction. Indeed, in Irish cities, most Irish shops went online during COVID-19 lockdowns thanks to government aid, but these traders continued to accumulate costs by operating their premises, though there were no customers coming through the door. Once life went back to normal in 2022, the phenomenon observed before the pandemic – the fall in footfall in physical shops – resumed, especially with high inflation in Ireland. For instance, the number of monthly trips to supermarkets has continued to decline: in 2022, on average, shoppers visited supermarkets 3.5 less often than in 2021 when COVID-19 restrictions were implemented.[43] This decrease could be explained by the fact that online shopping better fits with busy post COVID-19 schedules. Furthermore, in a context of high inflation, it “allows customers to be more considerate as they add items to their basket.”[44] In 2023, Irish customers returned to the shops (one additional trip per month on average compared to 2022), but they usually bought less per trip and they tended to value Irish brands in their grocery shopping. At the same time as they returned to the physical shops, they also bought more grocery online as there was a 6% increase compared to 2022.[45] Finally, despite an increase in both channels, the gap between online and traditional retailing is widening. As a result, we may wonder whether traditional shops will have enough customers to survive in the long term. If retailers have a dual revenue stream (bricks and clicks), they can keep their shops in Irish towns and cities to maintain contact with Irish consumers, an advantage that international companies do not have, except if they have local subsidiaries such as Tesco. In any case, if the Irish do not keep up the habit of shopping – whether physical or / and online – with Irish retailers, town centres will continue to decline. An Irish book shopper, Tomas Kenny from Kenny’s Bookshop in Galway, stated:

Traditional retail has been in a downward spiral for years. That has been made worse by Covid-19. But a move by Amazon will set in motion a vicious circle, particularly in smaller towns. There is a real danger we will see the non-grocery sector disappear altogether. If you have no conventional retailers left what are you left with? Nothing except for pubs, betting shops, nail bars, hairdressers and maybe pharmacies. And the pharmacies will be next.”[46]

Conclusion

So far, Ireland has tended to benefit from the rise of technology and the Internet, attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) and welcoming the European headquarters and some of the operational activities of major international companies in Internet-related sectors. Since the Celtic Tiger, a number of voices have been calling for the Republic to reduce the weight of those multinationals in its economy, thus rebalancing the economy in order to prepare for the future: what would happen if they left the island for a more attractive country?

COVID-19 has accelerated trends that had been underway for some time. Among the most notable changes are hybrid work and the shift to online sales. This shift to online activity could become a more permanent feature with implications for employment, business models and national added value. During the pandemic, the Irish chose to buy more products online from both Irish SMEs and international retailers. This could represent an opportunity for Irish businesses should they carry on their efforts to meet consumer expectations. For example, they could offer subscriptions, special offers, use augmented reality to sample products (such as furniture), etc. Whether Irish SMEs take their fair share depends on their investment in their online offering. The Irish government’s subsidies are a chance but this also highlights that Irish SMEs are still a long way from their international competitors: many SMEs are still struggling to deploy their services online, either because they do not consider it as a priority or because of the investment required.

The economic stakes involved in e-commerce are high, but it should not be at the expense of social stakes, notably the risk of job losses in stores and the decline of town centres, which could damage social cohesion. Historically major transformations of the Irish economy have been guided by the State, through planning and economic incentives. Will the incentives help the Irish economy strike the right balance between innovation and social cohesion, combining strong offline (bricks) and online (clicks) presence?

[1] The study was carried over 180 countries. The Republic of Ireland (after Ireland in this article) ranked third after Italy and the United Kingdom. However, during the three Irish lockdowns, the rules on international travel were “very lax”. P. CULLEN, “Ireland had EU’s most stringent lockdown this year, analysis finds”, The Irish Times, 7/05/2021,[https://www.irishtimes.com/news/health/ireland-had-eu-s-most-stringent-lockdown-this-year-analysis-finds-1.4557746].

[2] Central Statistics Office (CSO), “Quarterly National Accounts, Quarter 2 2020”, 7/09/2020, [https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/er/na/quarterlynationalaccountsquarter22020/#:~:text=Quarterly%20decline%20of%206.1%25%20in%20Real%20GDP&text=On%20a%20seasonally%20adjusted%20basis,7.4%25%20over%20the%20same%20period].

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) measures value of what is produced in a country whereas Gross National Product (GNP) measures how much of that value stays in the country. Usually, the difference between GNP and GDP is very small in one country but in Ireland it is quite significant because of the outflow of profits of foreign-owned multinationals, whether those profits are made in Ireland or elsewhere in the world. This is why GDP is rarely used for the Irish economy. Many multinationals repatriate their profits in Ireland to benefit from the very low corporation tax rate (12,5 %).

[3] CSO, “Quarterly National Accounts, Quarter 1 2009”, 30/06/2009, [https://www.cso.ie/en/media/csoie/releasespublications/documents/economy/2009/qna_q12009.pdf].

[4] CSO, “Quarterly National Accounts, Summary 2020”, 2020,[ https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-nie/nie2020/summary/].

[5] CSO, “Quarterly National Accounts, National Income and Expenditure 2020”, 15/07/2021, [https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-ana/annualnationalaccounts2021/].

[6] BANQUE MONDIALE, “GDP Growth (annual %)”, [https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG].

[7]Although the distorting effects of multinational activity in the Irish economy have been the subject of much discussion over three decades now, this sector continues to have a strong presence in the national economy.

[8] « Ont subi une contraction de la demande intérieure (-10,4% pour la consommation finale privée et -22,1% pour l’investissement en 2020) ». MINISTERE DE L’ECONOMIE, DIRECTION GENERALE DU TRESOR, « Irlande, Présentation de l’économie irlandaise », [https://www.tresor.economie.gouv.fr/Pays/IE/presentation-de-l-economie-irlandaise].

[9] It should be noted that the e-commerce sector is worth around €7 billion in Ireland and the Wolfgangdigital study covered a sample of transactions representing around 7% of the entire Irish e-commerce market. 7% is a sample of transactions which is wider than that of opinion polls. Nonetheless, there might be a risk of sample bias, as Revolut is an online bank and therefore potentially attracts a younger and/or more educated clientele who is more willing to use ecommerce. A. COLEMAN, “On the Money: the Irish E-commerce Report 2021”, Wolfgangdigital.com, 18/02/2021, [https://www.wolfgangdigital.com/blog/irish-ecommerce-report-2021/].

[10] CENTRAL BANK OF IRELAND, “Quarterly Bulletin 01/01/2021”, [https://www.centralbank.ie/docs/default-source/publications/quarterly-bulletins/qb-archive/2021/quarterly-bulletin-q1-2021.pdf?sfvrsn=5].

[11] A. HOPKINS and M. SHERMAN, “Behind the Data, How has the Covid-19 Pandemic Affected Daily Spending Patterns?”, Central Bank of Ireland, April 2020.

[12] CENTRAL BANK OF IRELAND, op. cit., p. 23.

[13] Ibid.

[14] .IE We are Ireland online, “Tipping Point, How e-commerce can reignite Ireland’s post-Covid-19 economy”, 20/08/2020, p. 4, [https://www.weare.ie/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/IE-Tipping-Point-Report-2020.pdf].

[15] Irish consumers generally shop on British, Chinese and American websites, [https://www.jpmorgan.com/europe/merchant-services/insights/reports/ireland], (accessed 15/06/2022).

[16] .IE We are Ireland online, “Tipping Point, How e-commerce can reignite Ireland’s post-Covid-19 economy”, 20/08/2020, p. 5, [https://www.weare.ie/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/IE-Tipping-Point-Report-2020.pdf].

[17] S. BUCKLEY, “Blacknight Podcast: Record breaking May sees over 7,000 new .ie registrations”, .IE We are Ireland online, 10/06/2020, [https://www.iedr.ie/increase-in-ie-registrations/].

[18] CENTRAL BANK OF IRELAND, op. cit.

[19] Registrations for websites with an internet address finishing with .ie (for Ireland).

[20] .IE We are Ireland online, “.IE Domain Profile Report 2022”, 2023, p. 2, [https://www.weare.ie/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/IE-DPR-2022.pdf].A graph of website registrations in Ireland between 2018 and 2022 is provided on page 5 of the report.

[21] D. THOMAS, “Ireland: Responding to the Covid-19 Crisis – Protecting Entreprises, Employment and Incomes”, Secretariat Covid-19, Working Paper Series, May 2020, [http://files.nesc.ie/nesc_background_papers/c19-3-ireland-case-study.pdf].

[22] With an e-tailing strategy. ENTREPRISE IRELAND, “Funding Supports”, Nov. 2023, [https://www.enterprise-ireland.com/en/funding-supports/Online-Retail/Online-Retail-Scheme/].

[23] THIS UNIT, “Covid-19 Online Retail Scheme”, This Unit, [https://thisistheunit.com/covid-19-online-retail-scheme/], accessed 15/05/2022.

[24] ENTREPRISE IRELAND, “Minister English announces €5m in grants to retail sector through COVID-19 Online Retail Scheme administered by Enterprise Ireland”, 30/06/2021, [https://www.enterprise-ireland.com/en/news/pressreleases/2021-press-releases/minister-english-announces-euro-5m-in-grants-to-retail-sector-through-covid-19-online-retail-scheme-administered-by-enterprise-ireland.html].

[25] In Ireland, micro-businesses are firms with 1-9 employees. According to the latest Business Demography CSO survey, micro-businesses account for 92,4 % of firms in Ireland. CSO, “Business Demography 2021”, 25/08/2023, [https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-bd/businessdemography2021/keyfindings/].

[26] “In 2019, there were 1,218 applications for the Scheme; this year, between mid-March and early-June alone, there were 3,962, representing three years’ worth of applications in less than three months.” IRISH BUSINESS FOCUS, “Ministers Humphreys And Bruton Expand Trading Online Scheme By €14.2m As Part Of The Government’s Ongoing Covid-19 Response”, Irish Business Focus, 08/06/2020, [https://irishbusinessfocus.ie/government/ministers-humphreys-and-bruton-expand-trading-online-scheme-by-e14-2m-as-part-of-the-governments-ongoing-covid-19-response/].

[27] Ibid.

[28] In 2018, fewer than 1,000 businesses had received assistance. During the pandemic, over 12,000 applications were approved for the scheme in 2020. NESC, Digital Inclusion in Ireland: Connectivity, Devices, and skills, Council Report, June 2021, no. 154, p. 43, [http://files.nesc.ie/nesc_reports/en/154_Digital.pdf].

[29] ‘Future Jobs Ireland’ was launched in 2019 when Ireland was nearing full employment in order to increase quality jobs to increase living standards and be less vulnerable to job losses, [https://www.gov.ie/en/topic/9e2f5-future-jobs-ireland/].

Launched in 2011 by the Irish Government, ‘Springboard+’ provides free higher education (from certificate to Master’s Degree) for jobseekers to upskill or reskill in areas where there are skill shortages or employment opportunities (ICT, Medical technologies, cybersecurity, online retail, sustainable energy and creative industries).

‘Skillnet Ireland’ is a business support agency to upskill employees through different programmes.,[https://www.skillnetireland.ie/].

‘SOLAS Skills to Advance’ is a national initiative which provides upskilling and reskilling opportunities to employees in low-skilled jobs [https://www.solas.ie/programmes/skills-to-advance/].

[30] NESC, Digital Inclusion in Ireland: Connectivity, Devices, and skills, Council Report, June 2021, n°154, p. 10, [http://files.nesc.ie/nesc_reports/en/154_Digital.pdf].

[31] WOLFGANG DIGITAL, “On The Money December 10th – The Online Economy Report Q3 2020”, [https://www.wolfgangdigital.com/blog/on-the-money-december-10th-the-online-economy-report-q3-2020/].

[32] A. COLEMAN, “On the Money: the Irish E-commerce Report 2021”, Wolfgangdigital.com, 18/°2/2021.

[33] J.P. Morgan, Global e-commerce trends report, 2021, p. 80.

[34] .IE We are Ireland Online, “Tipping Point, How e-commerce can reignite Ireland’s post-Covid-19 economy”, 20 August 2020, p. 7-8.

[35] P. LALLY, C. H. M. VAN JAARSVELD, H. W. W. POTTS and J. WARDLE, “How are habits formed: Modelling habit formation in the real world”, European Journal of Social Psychology, vol. 40, issue 6, October 2010, p. 998-1009.

[36] 4 in 10 firms have to face delays in their supply chain. GRANTTHORNTON, “Irish businesses highlight effects of Brexit as supply chains and red tape hamper growth”, 16/08/2021, [https://www.grantthornton.ie/news-centre/irish-businesses-highlight-effects-of-brexit-as-supply-chains-and-red-tape-hamper-growth/].

[37] Amazon opened its first delivery station at Rathcoole in the southwest of Dublin in December 2020, expanded in September 2021 due to social distancing demands during the COVID pandemic and its second delivery site at Ballycoolin in the north west of Dublin in 2022. D. MACNAMEE and K. WOODS, “Amazon expands Rathcoole warehouse after ‘exceptionally busy’ Covid period”, The Business Post, 02/09/2021, [https://www.businesspost.ie/news/amazon-expands-rathcoole-warehouse-after-exceptionally-busy-covid-period/], AMAZON, “Amazon opens its first fulfilment centre in Ireland”, 08/09/2022, [https://www.aboutamazon.eu/news/operations/amazon-opens-its-first-fulfilment-centre-in-ireland].

[38] A. WECKLER, “Amazon.ie may be some time off, but giant new Irish warehouse is ready for it, say executives”, Irish Independent, 17/10/2022, [https://www.independent.ie/business/technology/amazonie-may-be-some-time-off-but-giant-new-irish-warehouse-is-ready-for-it-say-executives/42073701.html].

[39] Ibid.

[40] J. KEANE, “Amazon is raising eyebrows in Ireland with reports of a new e-commerce hub”, CNBC, 29/04/2021, [https://www.cnbc.com/2021/04/29/amazon-is-raising-eyebrows-in-ireland-with-reports-of-a-e-commerce-hub.html].

[41] .IE We are Ireland Online, “.IE Tipping Point 2022, Irish e-commerce and digital business in the post-Covid era”, March 2022, p. 2, [https://www.weare.ie/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/IE-Tipping-Point-Report-2022.pdf].

[42] Ibid, p. 4.

[43] Bord Bia (Irish Food Board), Irish Grocery Retail Market Overview, 2022, p. 2, [https://www.theconsumergoodsforum.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Global-Summit-2022_Irish-Retail-Scene.pdf].

[44] Ibid, p. 11.

[45] KANTAR, “Irish grocery sales and trips to the store increase as inflation hits lowest rate this year”, 24/07/2023, [https://www.kantar.com/uki/inspiration/fmcg/2023-wp-irish-grocery-sales-and-trips-to-store-increase-as-inflation-hits-lowest-rate-this-year].

[46] C. POPE, “Amazon’s arrival in Ireland will change the way we shop”, the Irish Times, 06/02/2021, [https://www.irishtimes.com/news/consumer/amazon-s-arrival-in-ireland-will-change-the-way-we-shop-1.4476364].

Bibliographie

.IE We are Ireland online, “.IE Domain Profile Report 2022”, January 2023, [https://www.weare.ie/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/IE-DPR-2022.pdf].

.IE We are Ireland Online, “Tipping Point, How e-commerce can reignite Ireland’s post-Covid-19 economy”, 20/08/2020, [https://www.weare.ie/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/IE-Tipping-Point-Report-2020.pdf].

.IE We are Ireland Online, “.IE Tipping Point 2022, Irish e-commerce and digital business in the post-Covid era”, March 2022, [https://www.weare.ie/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/IE-Tipping-Point-Report-2022.pdf].

AMAZON, “Amazon opens its first fulfilment centre in Ireland”, 08/09/2022, [https://www.aboutamazon.eu/news/operations/amazon-opens-its-first-fulfilment-centre-in-ireland].

BANQUE MONDIALE, “GDP Growth (annual %)”, [https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY. GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG], accessed 15/10/2022.

BORD BIA (Irish Food Board), Irish Grocery Retail Market Overview, 2022, [https://www.theconsumergoodsforum.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Global-Summit-2022_Irish-Retail-Scene.pdf].

BUCKLEY, Sean, “Blacknight Podcast: Record breaking May sees over 7,000 new .ie registrations”, .IE We are Ireland online, 10/06/2020, [https://www.iedr.ie/increase-in-ie-registrations/].

CENTRAL BANK OF IRELAND, “Quarterly Bulletin 01/01/2021”, [https://www.centralbank.ie/docs/default-source/publications/quarterly-bulletins/qb-archive /2021/quarterly-bulletin-q1-2021.pdf?sfvrsn=5].

COLEMAN, Alan, “On the Money: the Irish E-commerce Report 2021”, Wolfgangdigital.com, 18/02/2021, [https://www.wolfgangdigital.com/blog/irish-ecommerce-report-2021/].

CENTRAL STATISTICS OFFICE (CSO), Business Demography 2021, 25/08/2023, [https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-bd/businessdemography2021/key findings/].

CENTRAL STATISTICS OFFICE (CSO), “CPM01 – Consumer Price Index”, 09/11/2023, [https://data.cso.ie/].

CENTRAL STATISTICS OFFICE (CSO), “Quarterly National Accounts, Quarter 1 2009”, 30/06/2009, [https://www.cso.ie/en/media/csoie/releasespublications/documents/economy /2009/qna_q12009.pdf ].

CENTRAL STATISTICS OFFICE (CSO), “Quarterly National Accounts, Quarter 2 2020”, 07/09/2020, [https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/er/na/quarterlynationalaccounts quarter22020/#:~:text=Quarterly%20decline%20of%206.1%25%20in%20Real%20GDP&text=On%20a%20seasonally%20adjusted%20basis,7.4%25%20over%20the%20same%20period].

CENTRAL STATISTICS OFFICE (CSO), “Quarterly National Accounts, Summary 2020”, 2020, [https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-nie/nie2020/summary/ ].

CENTRAL STATISTICS OFFICE (CSO), “Quarterly National Accounts, National Income and Expenditure 2020”, 15/07/2021, [https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-na/quarterlynationalaccountsquarter12021final/ ].

COMPETITION AND CONSUMER PROTECTION COMMISSION (CCPC), Brexit and COVID-19: Consumer Behaviour and awareness while shopping online, March 2022, [https://www.ccpc.ie/business/research/market-research/ccpc-brexit-and-covid-19-consumer-behaviour-and-awareness-while-shopping-online/].

CULLEN, Paul, “Ireland had EU’s most stringent lockdown this year, analysis finds”, The Irish Times, 07/05/2021, [https://www.irishtimes.com/news/health/ireland-had-eu-s-most-stringent-lockdown-this-year-analysis-finds-1.4557746].

DUHIGG, Charles, The Power of Habit, London: Random House Books, 2012, 371 pp.

ENTREPRISE IRELAND, “Funding Supports”, Nov. 2023, [https://www.enterprise-ireland.com/en/funding-supports/Online-Retail/Online-Retail-Scheme/].

ENTREPRISE IRELAND, “Minister English announces €5m in grants to retail sector through COVID-19 Online Retail Scheme administered by Enterprise Ireland”, 30/06/2021, [https://www.enterprise-ireland.com/en/news/pressreleases/2021-press-releases/minister-english-announces-euro-5m-in-grants-to-retail-sector-through-covid-19-online-retail-scheme-administered-by-enterprise-ireland.html].

GOVERNMENT OF IRELAND, Economic recovery Plan 2021, Accompanying Background Paper: Accelerating Trends and Shifts, 2021, 63 pp., [https://assets.gov.ie/136523/03f31f12-10eb-4912-86b2-5b9af6aed667.pdf].

GRANTTHORNTON, “Irish businesses highlight effects of Brexit as supply chains and red tape hamper growth”, 16/08/2021, [https://www.grantthornton.ie/news-centre/irish-businesses-highlight-effects-of-brexit-as-supply-chains-and-red-tape-hamper-growth/].

HOPKINS, Andrew and Martina SHERMAN, “Behind the Data, How has the Covid-19 Pandemic Affected Daily Spending Patterns?”, Central Bank of Ireland, April 2020, [https://www.centralbank.ie/statistics/statistical-publications/behind-the-data/how-has-the-covid-19-pandemic-affected-daily-spending-patterns].

IRISH BUSINESS FOCUS, “Ministers Humphreys And Bruton Expand Trading Online Scheme By €14.2m As Part Of The Government’s Ongoing Covid-19 Response”, Irish Business Focus, 08/062020, [https://irishbusinessfocus.ie/government/ministers-humphreys-and-bruton-expand-trading-online-scheme-by-e14-2m-as-part-of-the-governments-ongoing-covid-19-response/].

J.P. MORGAN, Global e-commerce trends report, 2021, 115 pp., [https://www.jpmorgan.com /payments/global-ecommerce-trends-report].

KANTAR, “Irish grocery sales and trips to the store increase as inflation hits lowest rate this year”, 24/07/2023, [https://www.kantar.com/uki/inspiration/fmcg/2023-wp-irish-grocery-sales-and-trips-to-store-increase-as-inflation-hits-lowest-rate-this-year].

KEANE, Jonathan, “Amazon is raising eyebrows in Ireland with reports of a new e-commerce hub”, CNBC, 29/04/2021, [https://www.cnbc.com/2021/04/29/amazon-is-raising-eyebrows-in-ireland-with-reports-of-a-e-commerce-hub.html].

LALLY, Phillippa, Cornelia H. M. VAN JAARSVELD, Henry W. W. POTTS, Jane WARDLE , “How are habits formed: Modelling habit formation in the real world”, European Journal of Social Psychology, vol. 40, issue 6, October 2010, p. 998-1009, [https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/ejsp.674].

MACNAMEE Donald and Killian Woods, “Amazon expands Rathcoole warehouse after ‘exceptionally busy’ Covid period”, The Business Post, 02/09/2021, [https://www.businesspost.ie/news/amazon-expands-rathcoole-warehouse-after-exceptionally-busy-covid-period/].

MINISTERE DE L’ECONOMIE, DIRECTION GENERALE DU TRESOR, « Irlande, Présentation de l’économie irlandaise », 17/07/2022, [https://www.tresor.economie.gouv.fr /Pays/IE/presentation-de-l-economie-irlandaise].

NESC, Digital Inclusion in Ireland: Connectivity, Devices, and skills, Council Report, June 2021, n°154, [http://files.nesc.ie/nesc_reports/en/154_Digital.pdf].

Office for National Statistics (ONS), “Consumer price inflation tables”, 18/10/2023, [https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/inflationandpriceindices/datasets/consumerpriceinflation].

POPE, Conor, “Amazon’s arrival in Ireland will change the way we shop”, the Irish Times, 06/02/2021, [https://www.irishtimes.com/news/consumer/amazon-s-arrival-in-ireland-will-change-the-way-we-shop-1.4476364].

THIS UNIT, “Covid-19 Online Retail Scheme”, This Unit, [https://thisistheunit.com/covid-19-online-retail-scheme/], accessed 15/05/2022.

THOMAS, Damian, “Ireland: Responding to the Covid-19 Crisis – Protecting Entreprises, Employment and Incomes”, Secretariat Covid-19, Working Paper Series, May 2020, [http://files.nesc.ie/nesc_background_papers/c19-3-ireland-case-study.pdf].

WECKLER, Adrian, “Amazon.ie may be some time off, but giant new Irish warehouse is ready for it, say executives”, Irish Independent, 17/10/2022, [https://www.independent.ie/ business/technology/amazonie-may-be-some-time-off-but-giant-new-irish-warehouse-is-ready-for-it-say-executives/42073701.html].

Auteurs

Vanessa BOULLET

Université de Lorraine, InterDisciplinarité dans les Etudes Anglophones (IDEA), UR 2338

vanessa.boullet @ univ-lorraine.fr

Références

Pour citer cet article :

Vanessa BOULLET - "Vanessa BOULLET, Can e-commerce revive the Irish economy after Brexit and the Covid-19 pandemic?" RILEA | 2023, mis en ligne le 12/12/2023. URL : https://anlea.org/revues_rilea/can-e-commerce-revive-the-irish-economy-after-brexit-and-the-covid-19-pandemic/