Résumé

Dans cet article, nous étudions le modèle de microcrédit social porté par un établissement public de crédit et d’aide sociale : le Crédit Municipal, en région Atlantique. Dans un contexte où de plus en plus de personnes sont en « autonomie contrainte » faute d’accès aux mobilités, nous tentons d’établir un dialogue compréhensif entre le « New Paradigm of Mobilities » et le Convivialisme. Nos premiers résultats montrent que seulement quelques bénéficiaires-usagers du microcrédit social financent leur mobilité propre et inclusive, mais qu’en général le microcrédit social finance bien d’abord la mobilité (achat de véhicule d’occasion, réparation, permis de conduire) au service d’une inclusion sociale.

Mots-clés : banque solidaire, micro-crédit, France, mobilité inclusive

Abstract: In this research paper, we examine the social microcredit model provided by a French public credit and social aid institution: Crédit Municipal in the French Atlantic region. At a time when more and more people face “limited autonomy” due to lack of access to means of transport, we try to establish a comprehensive dialogue between the New Paradigm of Mobilities (NPM) and the literature on Convivialism. Our first findings show that only a few beneficiary users of social microcredit can finance their own inclusive mobility without being overburdened with debt; however, they also indicate that in general social microcredit must finance social inclusive mobility (buying a second-hand car, accessing driving licence services, or repairs).

Keywords: social banking, microcredit, France, inclusive mobility

Texte

| Method Insert: We studied more than 700 social microcredit requests dealt with by the French public lending service “Crédit Municipal Nantes-Angers-Rennes-Tours”. This social banking process takes place in partnership with local social action centers, using social and financial accompanying tools such as: social microfinance for inclusive mobility. We compiled a database to develop our financial fragility indicator. In this research paper, we try to demonstrate how social customers have benefited from this social microfinance measure to finance their inclusive mobility. |

Introduction: Social microcredit and mobilities: human wellbeing under duress

Around 1911, the first car drove through the town of Vézin. […] To watch the show, the schoolteacher, Mr. Mailleux, stopped his class and led his pupils outside. They found themselves by the side of the road admiring the black Torpedo […]. It belonged to the Nantes industrialist who owned the Hermitage dairy.[1]

The archivist points out that the year 1911 was that of the opening of the oldest registry of identification documents for the owners of cars (92.2% of declarations), motorcycles (4.6%), and trucks (2.2%). Moreover, he also underlines the long social history of inequalities in access to cars for social inclusive mobility purposes. If we consider the latest report from the French Inclusive Mobility Laboratory[2] which concludes that “in France, 25% of people are being constrained in their mobility,”[3] it seems clear that we are faced with a major social problem which could be alleviated by social microcredit. Is our working hypothesis realistic?

The website of the Banque Populaire Grand Ouest tells us that this cooperative bank aims to “promote banking inclusion” in support of commuting mobility. Indeed, some of its customers experience banking difficulties, either because of personal accidents or because of financial exclusion due to over-indebtedness. Therefore, its Grand Ouest cooperation social banking entity offers to help these member clients “by offering them personal microcredits in order to strengthen their mobility and support their employability.”[4] “Social inclusiveness” is thus made possible here by technical mobility. However, mobility encompasses far more than the ability to commute to work. Mobility for economically disadvantaged people also refers to the possibility to interact socially with family or friends. If they do not have access to this form of social mobility, then they face social exclusion. So, can we consider that, in social banking, inclusive mobility includes both commuting mobility and relational mobility?

According to the report from the IML, inclusive mobility appears to be part of a solidarity-based strategy to fight poverty and social exclusion in order to support geographical mobility for unemployed people. Thus, the following objectives have been set: to develop mobility platforms across the region and to create effective public policy to support inclusive interregional mobility for job search. Drawing from Reifner’s work[5], we can define social banking as banking practices which provide support to people excluded from banking services or experiencing financial fragility; this type of banking provides social banking tools such as social microcredit, solidarity-based micro savings and social microinsurance[6]. Thus, under this definition and in the context of the issue of inclusive mobility, in this paper we aim to answer the following question: how can social microcredit promote inclusive commuting and relational mobility?

Therefore, we raise the following key question: how can social microcredit be both an issue and an opportunity to assist social inclusive mobility?

In order to offer preliminary answers to this central question, we first present an analysis, based on a review of social science literature, of the opportunities and issues of social microcredit for the financing of social inclusive mobility. Second, we offer an initial analysis of the findings of local research carried out in the two French western regions of Bretagne and Pays de la Loire, more specifically in Nantes Metropole (the city of Nantes). Our approach is a mixed method integrating both qualitative and quantitative data.

Opportunities and issues of social microcredit as a means to assisting social inclusive mobility

It is important with regard to the prevention of over-indebtedness. It seems fundamental to me. We can observe it very clearly, and this afternoon I will be chairing an optional services commission. We see very clearly that financial fragility leads to social fragility, and it is a kind of downward spiral. We often see this case: a car breakdown, a hefty bill, something unexpected brings down a system that is already difficult to keep in balance. (Social worker, in a public community center).[7]

Regarding the theoretical framework used, the social science analysis presented below takes a transdisciplinary approach based on the “New Mobilities Paradigm” (NPM) and a convivialist approach, which will be discussed.

Social and inclusive mobility: Approaches in the social sciences.

Mobility through social and inclusive dimensions was first studied in the field of social sciences, namely through sociology and social geography. It is important to note: “Mobility is an all-encompassing concept, and all the notions that result from it (travel, transport, migration, etc.) must be delineated, as they are too often confused with it.”[8] Indeed, mobility can be characterized by the following three dimensions (table 1):

Table 1 – The characteristics of mobility in social sciences: sociology and social geography

| Whole conditions | Structuring elements |

| Social | – Free mobility empowerment, – The ability to evolve or not within social groups, – The social dimensions of mobility (movement, personal styles, etc.). |

| Geographical | – The nature and configuration of spaces, – The legal environment of mobility, – Plural isotropies. |

| Economic | – The individual costs of mobility, – The collective costs of mobility, – Mobility opportunities and methods (time, distance). |

Source: Pascal GLEMAIN, drawing from Michel LUSSAULT and Mathis STOCK, « Mobilités » in Jacques LEVY and Michel LUSSAULT (eds), Dictionnaire de la géographie et de l’espace habité, Paris : Belin, (2003)

The matrix above facilitates our understanding of Desjeux’s approach. According to this author: “Mobility is such a daily activity that we can forget that it is also a means of analysing life in society. […] The variability of mobility relates to three major material, social and symbolic dimensions whose very content varies depending on the scale of observation chosen.”[9] In other words, when beneficiaries live in rural areas or when they do not have a car, social microcredit can be a solution not only to find employment, but also to access a normal lifestyle.

These citizens suffer the most from denied access to social relationships and to culture. Moreover, they are also the most financially constrained. Indeed, citing INSEE data, Le Breton highlights that “in 2017, rural households spent 16% of their disposable incomes to finance their mobility, as opposed to only 12% in Paris”[10]. Non-inclusive mobility is a possible factor promoting social exclusion[11]. Finally, under the three social, geographical and economic conditions listed above, inclusive mobility appears as a capability for social microcredit recipients. Let us define the term: capability can be defined as “the capacities of individuals to lead their lives as they want, therefore in accordance with the values that they endorse and that they are right to value”[12].

In our “hypermobile” society, characterised by high levels of mobility and evolution, the inability or incapability to be mobile becomes a severe constraint for people who cannot afford to finance their mobility. Therefore, we agree with the following conclusion: “For individuals and groups, the importance of distance through mobility is not limited to physical current movement and its techniques (which we call transport), but also concerns the movement of ideologies and the technologies unfolding in a society.” [13]

In Human and Social Sciences (HSS), the emergence of the term “mobility” to refer to modes of spatial travel is relatively recent[14]. Social geographers have also developed research programmes on mobility with a specific focus on people suffering from disabilities. For instance, Leray and Séchet[15] have examined the non-inclusive mobility of single-parent families in Brittany. The authors describe the financial constraints of single-parent families and highlight that they are more vulnerable than inclusive families. What answers can management science and its comprehensive approach of “inclusive” mobility provide?

According to Bernard Sergot, Elodie Loubaresse and Didier Chabault, “Management science has paid relatively little attention to the analysis of the complex relationships between organizations and spatial mobility.”[16] While these three researchers invite other social researchers to investigate “the way in which human spatial mobility can influence organized collective action”, they only highlight research programmes in management science that address the growing geographical dispersion of workplaces[17], or programmes in organisation studies[18]. However, those research programmes do not examine human behaviour and social and economic wellbeing. Under our approach, we suggest using the transdisciplinary movement of the New Mobilities Paradigm (the NMP) because it offers what Sergot et al. call “a new reading of social phenomena in the light of spatial mobility”[19]. The authors stress that the NMP considers “the world as a composite of relationships rather than single entities” and “social dimension to take shape with a view to foster mobility”[20]. In social sciences, the Third Working-places research programmes have aimed to qualify the new interaction between mobility and social or labour relationships[21]. Several fields of management science have also examined mobility and work (table 2):

Table 2 – Management science research into spatial mobility

| Aims | Authors | Limitations | |

| HRM | To study individual work evolution: 1- nomadic careers, or workers without borders; 2 – international mobility for workers

| 1 – Arthur and Rousseau, 1996; Cadin et al., 2003; Inkson et al., 2012. 2- Bonache et al., 2010; Goxe and Paris, 2014; Saba and Chua. | – a spatial analysis of professional mobility. – no analysis of motivations. |

| New Technologies of Information and Communication | To study mobility through new technical opportunities: 1 – new technologies; 2 – Tele-working, co-working centres. | 1 – Besseyre des Horts and Isaac, 2006; Fernandez and Marrauld, 2012. 2 – Hislop and Axtell, 2007; Sewell and Taskin, 2015; Taskin, 2010. | – Mobility is explained and its hybridity is defined by moving people and objects (PCs, smartphones, graphics tablets, etc.). – How do those moving objects change the relationships between time and space? |

Source: Pascal GLEMAIN, drawing from Bernard SERGOT, Elodie LOUBARESSE and Didier CHABAULT, « Mobilités spatiales et organisation: proposition d’un agenda de recherché », Management international / International Management / Gestiòn Internacional, 22(4), 2018.

If we understand the “multiplicity of mobilities”[22] as the mobilities of objects (economic and social), of temporality (durations, rhythms, frequencies), and of scale (local, regional, national, international), the NMP’s thesis seems compelling for our theory of a social microcredit aimed at promoting inclusive mobility. We will now examine the NMP- Convivialism theoretical couple.

What is the convivialist contribution to inclusive mobility research programmes?

“A convivial society is one that gives people the possibility of exercising the most autonomous and creative action, through tools which are less controllable by others. Productivity is combined in terms of having, conviviality in terms of being.”[23] According to Illich, cars are social and economic tools which can enable human wellbeing, in addition to reducing social fragility. Therefore, we think that it is possible to combine the NMP and Convivialism.

Under the convivialist approach[24], in the context of an energy crisis, social inequalities appear with regard to access to energy resources: increasing fuel prices entail a form of “radical monopoly”, i.e., a consequential effect. By “radical monopoly”, we refer to “a type of domination by a product which goes well beyond what is usually designated as such”[25].This author points out that “when people have to be transported and become powerless to move around without a motor, that is radical monopoly”[26]. In other words, as a frequent result of family and personal organisational constraints, the most vulnerable households are subjected to this radical monopoly. However, to “be citizens”, they must have access to a motorised vehicle in order to sustain their own inclusive mobility.

Illich draws the following conclusion: “Believing in the possibility of clean energy as a solution to all problems represents an error of political judgement: we imagine that equity and energy consumption can grow together.”[27] Indeed, not only do the economically disadvantaged lack the sufficient financial resources to buy electric cars, but they also face mobility access problems, such as repairing their old cars or financing their driving licence. Those citizens are called “users” by Illich. According to him, “the user lives in a world which is not that of people endowed with autonomy”[28]. These “users” are socially, economically and geographically dependent on their “mobility units”[29] with, for example, “a car constituting as much a space as an instrument of mobility”. Data from the French Observatory of Banking Inclusion reveals that “more than 90% of the personal microcredits that are granted are used to finance expenses aimed at promoting mobility: purchasing or repairing a vehicle necessary to performing a professional activity, or obtaining a driving licence for example”[30]. But a social banking approach is not sufficient to demonstrate the potentiality of using social microcredit as a component of social innovation with a view to promoting inclusive mobility[31].

Concluding this first part, it is essential to highlight the convergence of the NMP and Convivialism in order to explain the potential of social microcredit to finance both inclusive commuting mobility and inclusive relational mobility in users’ social relationships with families and friends. Let us now examine the viability of this theoretical hypothesis.

Testing the viability of social microcredit as a useful means to promote inclusive mobility

Since the release of our FIMOSOL’s research report, social microcredit has largely been used to finance mobility. This use has been encouraged by the French legal environment, in particular the “Loi d’Orientation Mobilité” which lays out a common action plan to promote solidarity mobility. We know inclusive mobility to be dependent on the territory’s characteristics (the availability or lack of public transport options, car dependency, and so on). Currently, more than 33% of the French population live in peri-urban or rural areas. Therefore, they find themselves impacted by the mobility imperative to access healthcare services and schools, to maintain relationships with family and friends, and to access cultural or sports activities. Therefore, in one of the two north-western regions of France, CEREMA performed a dual mobility assessment (formal and informal) in order to find solutions for a more inclusive mobility model. The first objective is to decrease the financial impact of mobility: support towards mobility, social utility transport for individuals, temporary access to a bicycle or to a car, leasing solutions, repair services. However, this report does not mention solutions such as social microcredit, even if the region supports it with its “contrats de mobilité opérationnels”[32] which reflect “the desire of an area to have a better network in solidarity-based rental and repair”[33] for example with solidarity garages. What have we learned on that issue since the 2000s?

Lessons from the 2000s…

The findings of our first research reports[34] have shown that spatial mobility is both a condition and a consequence of social and professional mobility, as well as a possibility and a constraint[35]. In that research, which we carried out for the Interdepartmental Delegation for Social Innovation and Social Economy, we stressed the importance of the “mobility-social microcredit” couple. We interviewed the co-founder and director of the association Solidarauto, who stated the following:

We realized via the unit which sets up microcredits within Secours Catholique […] that 70 to 80% of microcredit requests were intended either for the repair or the purchase of vehicles and very often, when these people had obtained a microcredit to buy a vehicle, then they came back to ask for a microcredit to repair the vehicle and so we thought that, without a doubt, something had to be done for this audience, hence the idea of setting up a solidarity garage.[36]

A solidarity-based garage is a social enterprise which receives car donations. Those cars are free for the solidarity-based garage, which can sell them at a lower price to people who benefit from social assistance from public institutions, such as social organisations or public social welfare centres (CCAS in French).

Those public users can access car repair services. Customers who can afford to pay the standard price can join the association, but they must pay the full price for repair services as they would in a market-based garage. In 2013, the solidarity-based garage had 744 members, including 518 users and 226 full-price paying customers; 70% of the users had been granted a social microcredit through a cooperation between a local cooperative bank and a social organisation. Let us focus on public credit and social assistance, with the case of a local credit and social aid financial institution.

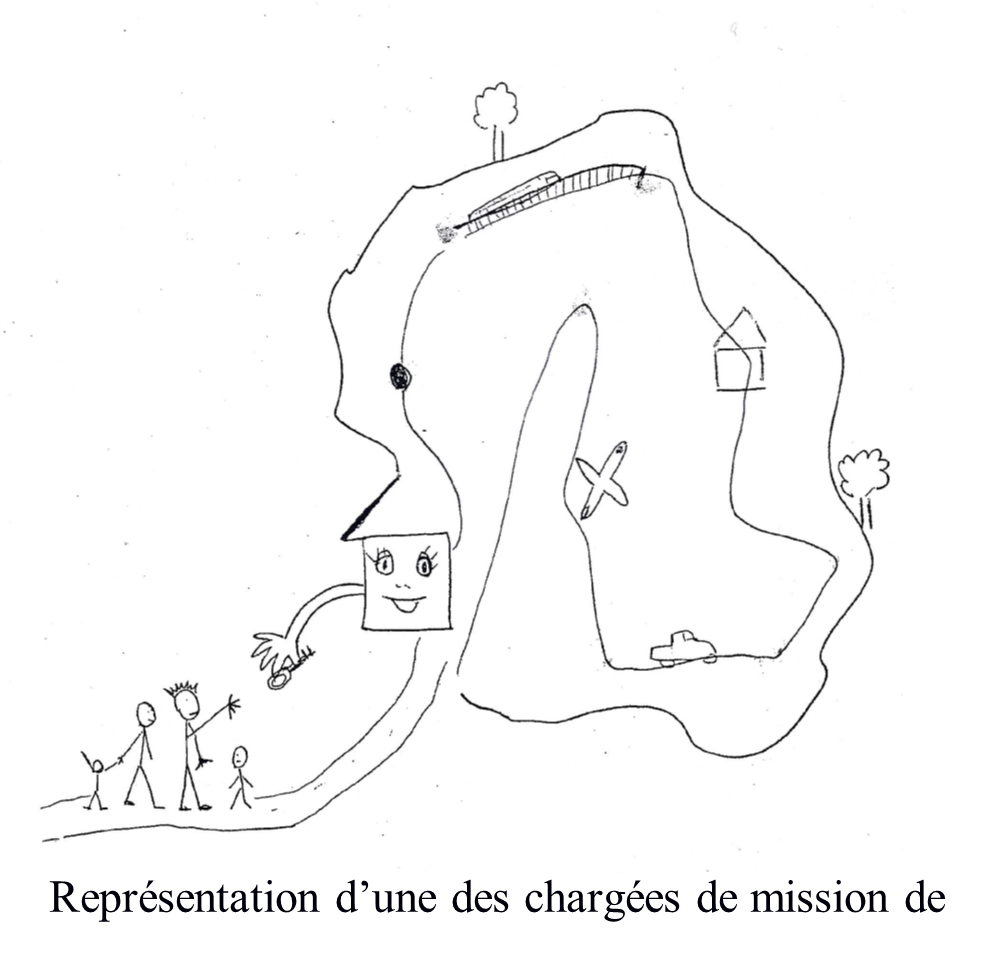

The solidarity-based cooperation between the public credit institution (Crédit Municipal) and the local centre of social assistance is based on a form of social microcredit, the “Prêt Stabilité” or stability loan, which is financed from their own funds. The results from our research carried out for FIMOSOL[37] demonstrate that 85.8% of the stability loans that are granted are used to finance the purchase of a car, 7.1% for car repairs, and 7.1% to finance a driving licence. We asked users who had been granted a social microcredit to represent their feelings regarding inclusive mobility within a mind map. Reproduced below is an example:

Mind Map created by one of the task officers of the association « Une famille, un Toit », 20 April 2009

A male user from the French western area stated the following:

Without a car [I am] nothing: without a car I can’t do anything, I stay at home and I’m bored. […] God knows what I can do without a car. It means I cannot do anything by myself, that’s not in my culture. But with a car I’m independent. I can go and see my brother (who lives near Nantes). I go out. I take my mother shopping because she doesn’t have a car. You can imagine what I was unable to do. I had to walk to the village. I had to take the bus to go and see my brother but it’s not convenient. My car is my whole life.[38]

That statement and the mind map reproduced above point towards the same conclusion: indeed, those two examples illustrate the possibility offered by social microcredit to access inclusive mobility. We can therefore conclude, according to the first findings of 2010, that social microfinance supports inclusive mobility. What are the current findings?

…and social banking innovation in 2024 for inclusive mobility

Here, we examine a sample from public research into social microcredit in the west of France. Two public actors are concerned: a public credit and social aid institution (Crédit Municipal) and a local public social action centre, between 2012 and 2023. Let us consider a sample of women (N=68). The starting year of the social microcredits they applied for is 2019 and the term is 2023. More than 69% of these women are unmarried and single. 97% of them live in public low-rent housing, and 3% of them live with their parents. Only 40% of them are French, and more than 45% live away from their parents. Their status on the labour market is as follows (tab. 3):

Table 3 – 2019 female sample: status on the labour market

| OCCUPATIONAL CODE | Status on the labour market | Number (Xi) | % |

| 2 3 7 8 9 | Private sector employee Retired Unemployed Public sector (fixed-term) Private sector (fixed-term) | 20 5 38 1 4 | 29,41 7,35 55,88 1,47 5,88 |

| Total | 68 | 100 |

Source: Pascal GLEMAIN, drawn from the Crédit Municipal database, April-May 2025

What emerges from the overview of those 2019 female beneficiaries is a sense of employment fragility. Nearly 56% are unemployed, and only 29% have permanent work contracts as social workers. It should be useful at this point to break down to what ends social microcredit is used. We have defined several equations, which we present below:

[1] Inclusive mobility (Mob) = driving licence + buying own car + low mobility vehicle (bicycle) + repairing car or low mobility vehicle

[2] Home (Home) = electrical appliances + furniture + PC-Hifi-video + renovation or maintenance

[3] Sensitive Budget (BuFr) = microcredit renewal + bank overdraft + delays in paying bills + banking loans + new microcredit + debt restructuring

[4] Family (Fam) = holidays + family gatherings + leisure + travel

[5] Employment (Emp) = training to facilitate employability

Based on those five equations, the following results matrix can be produced for our female sample (table 4):

Table 4 – Thematic indices for social microcredit uses: female sample.

| Thematic indices | Number (Xi) | % |

| Mob Home BuFr Fam Emp | 24 16 20 6 2 | 35.30 23.53 29.41 8.82 2.94 |

| Total | 68 | 100 |

Source: Pascal GLEMAIN, drawn from the Crédit Municipal database, April-May 2025

The first social microcredit target for the women in this sample is inclusive mobility (35.3%). However, their home budget is fragile (29.41%), and they have to finance home furniture too. Regarding the microcredit commitments taken in 2019, these are the findings: in 2023 for 16.10% of them, in 2022 for 57.35%, in 2021 for 14.71%, in 2020 for 10.29 %, and in 2019 for 1.48%. Dates are now a significant explanatory variable to understand those women’s financial vulnerability. Social microcredit must combat such banking fragility.

The sociologist approach emphasizes that daily journeys are “of great diversity depending on the type of work (or non-work), habits or lacks of habit, in individual, social and family contexts which are necessarily significant, particularly due to the time (and mileage) constraints they impose.”[39] With our first quantitative variables, we have contributed to the understanding of the role of social microcredit with regard to inclusive mobility.

Conclusion: social microcredit for inclusive mobility: a new social banking strategy

In the general social geographical sense of the word, mobility is “all of the manifestations linked to the movement of social realities (humans, material and immaterial objects) in space.”[40] Mobility no longer refers only to “home-work” commuting. However, the French Banking Inclusion Observatory insists that personal or professional microcredit is aimed at people ‘excluded’ from the traditional banking system due to low creditworthiness and/or a social fragility. It must support both return to employment and small business entrepreneurship. In this paper, we have shown that social microcredit can finance, first, inclusive mobility and, second, low family budgets and the provision of social housing units. However, our first findings are derived from a sample of single women. Research must be carried out regarding single or married men as well as married women across the French western Atlantic regions in order to generalise the results of our research into social microfinance in France and Belgium.

___

NOTES

[1] « Vers 1911, la première voiture traverse le bourg de Vézin. […] Pour assister au spectacle, l’instituteur, Monsieur Mailleux, interrompt sa classe et fait sortir ses élèves. Ils se retrouvent sur le bord de la route et admirent cette torpédo noire. […] Elle appartient à un industriel nantais, propriétaire de la laiterie de l’Hermitage », Le Bulletin de Vézin le Coquet, n°21, p. 3. Quoted by Bruno GAUTHIER « Des voitures et des Hommes », Cahiers François Viète, n°5, 2003, p. 63.

[2] The Inclusive Mobility Laboratory is a Foundation operated by the French « Fondation Agir Contre l’Exclusion » (FACE).

[3] « En France, 25% des personnes sont contraintes dans leur mobilité », Francis DEMOZ and Marc FONTANES, Mobilité solidaire : pour un passage à l’échelle. Rapport du Laboratoire de Mobilité Inclusive, 2023, p.3.

[4] « En leur offrant des microcrédits personnels pour renforcer leur mobilité et soutenir leur employabilité », [https://publications.banque-france.fr/liste-chronologique/rapport-annuel-de-lobservatoire-de-linclusion-bancaire].

[5] Ugo REIFNER, « La finance sociale : des produits au service du développement communautaire et local », 2000, pp. 200-217, in INAISE, Banques et cohésion sociale, Paris : éditions Charles Léopold Mayer, 2000.

[6] Pascal GLEMAIN, Microfinance sociale, Rennes : éditions Apogée, 2021.

[7] Travailleur social en centre communal d’action sociale (CCAS) : « C’est important au regard du surendettement. Cela me semble fondamental. Nous observons cela clairement. Cet après-midi, j’étais en commission des services annexes. Nous constatons que la fragilité financière conduit à la fragilité sociale, et c’est une sorte de spirale. Nous voyons souvent ce cas : une voiture en panne, une lourde facture, quelque chose d’inattendu se produit et on est plus à l’équilibre ». Interview by the author.

[8] « La mobilité est un impensé, et toutes les notions qui en sont issues (voyage, transport, migration, etc.) sont souvent confondues avec elle » Michel LUSSAULT and Mathis STOCK « Mobilités », in Jacques LEVY and Michel LUSSAULT (dir.), Dictionnaire de la Géographie et de l’espace habité, Paris : Belin, 2003, p.623.

[9] « La mobilité est une activité quotidienne dont on oublie qu’elle est aussi une manière d’analyser la vie en société. […] La variabilité de la mobilité dépend de trois dimensions principales, matérielle, sociale et symbolique, dont de nombreuses variables dépendent d’un niveau d’observation choisi ».

Dominique DESJEUX, « Avant-Propos », in Philippe GERBER and Samuel CARPENTIER, (dir.), Mobilités et modes de vie, vers une recomposition de l’habiter, Rennes : PUR, 2013, p.7.

[10] « En 2017, les ménages ruraux dépensent 16% de leur revenu disponible pour financer leur mobilité, contre 12% pour les ménages parisiens », Eric LE BRETON, Mobilité, la fin du rêve ? Rennes, éditions Apogée, 2019, p.2.

[11] Eric LE BRETON, Bouger pour s’en sortir. Mobilité quotidienne et intégration sociale, Paris :Armand Colin, Coll. « Sociétales », 2005 and Eric LE BRETON, Mobilité, la fin du rêve, op. cit.

[12] « Les capabilités (capabilities) des personnes à mener leur vie comme elles le souhaitent, en accord avec les valeurs auxquelles elles adhèrent et auxquelles elles ont raison d’adhérer », Amartya SEN, Un nouveau modèle économique de développement. Justice, liberté, Paris : éditions Odile Jacob, 2003, p.33.

[13] « Pour les personnes et les groupes, l’importance de la distance à travers la mobilité n’est pas réduite au mouvement physique présent et ses techniques (que nous appelons transport), mais concerne aussi le mouvement des idéologies et les technologies qui se développent dans une société ». Michel LUSSAULT, L’Homme spatial. La construction sociale de l’espace humain, Paris : éditions du Seuil, 2007, p.58.

[14] Mathieu FLONNEAU and Vincent GUIGUENO (dir.), De l’histoire des transports à l’histoire de la mobilité, Rennes : Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2009.

[15] Frédéric LERAY and Raymonde SECHET, « Les mobilités sous contraintes des mères seules avec enfant(s) : Analyse dans le cadre de la Bretagne (France) », pp. 69-88 in Philippe GERBER and Samuel CARPENTIER (eds.), 2013, Mobilités et modes de vie. Vers une recomposition de l’habiter. Rennes : PUR, 2013.

[16] « Les sciences de gestion ont porté une relativement faible attention à l’analyse des relations complexes entre les organisations et la mobilité spatiale », Bernard SERGOT, Elodie LOUBARESSE and Didier CHABAULT, « Mobilités spatiales et organisation : proposition d’un agenda de recherche », Management international / International Management / Gestiòn Internacional, 22(4), 2018, pp 53–59.

[17] Donald HISLOP and Carolyn AXTELL, “The neglect of spatial mobility in contemporary studies of work: the case of telework”, New Technology, Work and Employment, vol.24, n°1, 2007, pp. 34-51; Laurent TASKIN, « La déspatialisation – Enjeu de gestion », Revue Française de Gestion, n°202, 2010 pp. 61-76; Graham SEWELL and Laurent TASKIN, “Out of sight, Out of mind in New World of Work ? Autonomy, Control and Spatiotemporal Scaling in Telework”, Organization Studies, Vol. 36, n°11, 2015, pp. 1507-1529.

[18] Frédérique CHEDOTEL, « Comment intervenir en temps réel à l’autre bout du monde ? », Revue Française de Gestion, n°226, 2012, pp. 151-163; Jana COSTAS, “Problematizing mobility: a metaphor or stickness, non-places and the kinetic elite”, Organization Studies, vol.43, n°10, 2013, pp. 1467-1485 ; Bernadette LOACKER and Martyna ŚLIWA, “Moving to stay in the same place ? Academics and theatrical artists as examplars of the mobile middle”, Organization, Vol .23, n°5, 2016, pp. 657-679.

[19] « Une nouvelle lecture d’un phénomène social à la lumière de la mobilité spatiale », Bernard SERGOT, Elodie LOUBARESSE and Didier CHABAULT, « Mobilités spatiales et organisation : proposition d’un agenda de recherche », op. cit.

[20] According to SERGOT et al., « Mobilités spatiales et organisation », 2018, p. 54, op. cit.

[21]Leonhard DOBUSCH and Dennis SCHONEBORN, “Fluidiy, Identity and Organizationaliy: The Communicative Construction of Anonymous,” Journal of Management Studies, 52 : 8, 2015, pp. 1005-1035; Pascal GLEMAIN, Microfinance sociale, Rennes : éditions Apogée, 2021 ; Pascal GLEMAIN (ed), Emmanuel BIOTEAU, Brigitte CHARLES-PAUVERS, Jean-Yves DARTIGUENAVE, Sigried GIFFON and Gaël HENAFF, Les défis de la microfinance sociale face à la fragilité financière et aux mobilités, Rapport de recherche au Crédit Municipal de Nantes-Angers-Rennes-Tours, avec le soutien de la Banque de France Pays de la Loire et la Banque Populaire Grand Ouest, 2024.

[22] Bernard SERGOT et al., « Mobilités spatiales et organisation », 2018, op. cit., p. 55.

[23] « Une société conviviale est une société qui donne à l’homme la possibilité d’exercer l’action la plus autonome et la plus créative, à l’aide d’outils moins contrôlables par autrui. La productivité se conjugue en termes d’avoir, la convivialité en termes d’être », Ivan ILLICH, La convivialité, Paris : éditions du Seuil, 1973, p.43.

[24] Alain CAILLE, Marc HUMBERT, Serge LATOUCHE and Patrick VIVERET, De la convivialité. Dialogues sur la société conviviale à venir, Paris : La Découverte, 2011 ; Marc HUMBERT, Vers une civilisation de la convivialité, Rennes : éditions Goater, 2013.

[25] « Par monopole radical, [j’entends] un type de domination par un produit qui va bien au-delà de ce que l’on désigne ainsi à l’habitude », Ivan ILLICH, La convivialité, 1973b, op. cit., p. 79.

[26] « Que les gens soient obligés de se faire transporter et deviennent impuissants à circuler sans moteur, voilà le monopole radical » Ibid, p. 81.

[27] « Croire en la possibilité d’une énergie propre, comme solution à tous les maux, représente une erreur de jugement politique : on s’imagine que l’équité et la consommation d’énergie pourraient croître ensemble », Ibid, p. 13.

[28] « L’usager vit dans un monde qui n’est pas celui des personnes douées d’autonomie », Ibid, p. 22.

[29] Michel LUSSAULT, L’Homme spatial. La construction sociale de l’espace humain. Paris : éditions du Seuil, 2007. p. 33.

[30] Observatoire de l’inclusion bancaire, Rapport annuel 2020, p. 12.

[31] Denis HARRISON and Jacques BOUCHER, « La co-production du savoir sur l’innovation sociale », Économie et Solidarités, vol. 41, N° 1-2, 2011, pp. 3-8.

[32] “Operational mobility contracts”

[33] Emmanuelle DUTERTRE, Pascal GLEMAIN and Elizabeth POUTIER., « Une innovation sociale en économie solidaire : le cas Solidarauto », Humanisme & Entreprise, 2013/3, n°313, 2013, pp. 51-64.

[34] FIMOSOL, Analyse interdisciplinaire des expérimentations locales du microcrédit social: premiers résultats en Pays de la Loire, Poitou- Charentes et Seine Maritime. Rapport de recherche au Haut-Commissariat aux Solidarités Actives et à la DIIESES. Under the scientific responsibility of Pascal GLEMAIN, 2010. FIMOSOL, Le microcrédit personnel garanti : une analyse transdisciplinaire de l’accompagnement dans le cadre d’un système bancaire solidaire. Rapport de recherche à la Direction Générale à la Cohésion Sociale et au Ministère Délégué à l’ESS. Under the scientific responsibility of Pascal GLEMAIN, 2012.

[35] Denis MARTOUZET, « Mobilités résidentielles, parcours professionnels et déplacements quotidiens : spatialités emboîtées et construction de l’habiter », pp. 49-65, in Philippe GERBER et Samuel CARPENTIER (eds.), Mobilités et modes de vie. Vers une recomposition de l’habiter, Rennes : Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2013.

[36] « Nous avons réalisé via le dispositif mis en place par le Secours Catholique que 70 à 80% du microcrédit étaient affectés la réparation ou à l’achat d’un véhicule et très souvent, quand ces personnes ont obtenu un microcrédit pour acheter un véhicule, ou qu’ils reviennent demander un microcrédit pour réparer leur véhicule, alors nous pensons de manière certaine que quelque chose a été réalisé pour cette issue, telle que l’idée de créer un garage solidaire ». Emmanuelle DUTERTRE, Pascal GLEMAIN and Elizabeth POUTIER., « Une innovation sociale en économie solidaire : le cas Solidarauto », Humanisme & Entreprise, 2013/3, n°313, 2013, pp. 51-64.

[37] FIMOSOL, Analyse interdisciplinaire des expérimentations locales du microcrédit social : premiers résultats en Pays de la Loire, Poitou- Charentes et Seine Maritime, 2010, op. cit.

FIMOSOL, Le microcrédit personnel garanti : une analyse transdisciplinaire de l’accompagnement dans le cadre d’un système bancaire solidaire, 2012, op. cit.

[38] « Sans voiture, je ne suis rien. Sans voiture, je ne fais rien. Je reste chez moi et je m’ennuie. Dieu sait ce que je peux faire sans voiture. Cela signifie que je ne peux rien faire par moi-même, ce n’est pas dans ma culture. Mais avec une voiture je deviens indépendant. Je peux aller voir mon frère qui habite à Nantes. Je sors. J’emmène ma mère faire ses courses parce qu’elle n’a pas de voiture. Vous imaginez ce que je ne pouvais pas faire. Je devais aller à pied au village. Je devais prendre le bus pour aller voir mon frère mais, ce n’est pas pratique. Ma voiture c’est toute ma vie ». Pascal GLEMAIN, interview, March 2025.

[39] « Tous les évènements liés au mouvement des réalités sociales (les humains, les objets matériels et immatériels) dans l’espace ». Denis MARTOUZET, « Mobilités résidentielles, parcours professionnels et déplacements quotidiens : spatialités emboîtées et construction de l’habiter », op. cit., p. 59.

[40] Les mobilités quotidiennes sont « d’une grande diversité dépendant du type de travail (ou non-travail), des habitudes et des manques d’habitude, en contextes individuels, social ou familial, qui sont nécessairement significatifs dus aux contraintes de temps qu’ils imposent », Michel LUSSAULT and Mathis STOCK, « Mobilités », 2003, op. cit., p. 622.

Bibliographie

CAILLE, Alain, Marc HUMBERT, Serge LATOUCHE and Patrick VIVERET, De la convivialité. Dialogues sur la société conviviale à venir, Paris : La Découverte, 2011.

CHEDOTEL, Frédérique, « Comment intervenir en temps réel à l’autre bout du monde », Revue Française de Gestion, n°226, 2012, pp. 151-163.

COSTAS, Jana, “Problematizing mobility: metaphor or stickiness, non-places and the kinetic elite”, Organization Studies, vol.43, n°10, 2013, pp. 1467-1485.

DEMOZ, Francis and Marc FONTANES, Mobilité solidaire : pour un passage à l’échelle, Rapport du Laboratoire de Mobilité Inclusive, 2023

DESJEUX, Dominique, « Avant-Propos », pp. 7-11, in Philippe GERBER and Samuel CARPENTIER (dir.), Mobilités et modes de vie, vers une recomposition de l’habiter, Rennes : PUR, 2013.

DOBUSCH, Leonhard and Dennis SCHONEBORN, “Fuidity, Identity and Organizationaliy: The Communicative Construction of Anonymous”, Journal of Management Studies, 52:8, Quelle, 2015, pp. 1005-1035.

DUTERTRE, Emmanuelle, Pascal GLEMAIN and Elizabeth POUTIER, « Une innovation sociale en économie solidaire : le cas Solidarauto », Humanisme & Entreprise, 2013/3, n°313, 2013, pp. 51-64.

FIMOSOL, Analyse interdisciplinaire des expérimentations locales du microcrédit social: premiers résultats en Pays de la Loire, Poitou- Charentes et Seine Maritime. Rapport de recherche au Haut-Commissariat aux Solidarités Actives et à la DIIESES. Under the scientific responsibility of GLEMAIN, Pascal, 2010.

FIMOSOL, Le microcrédit personnel garanti : une analyse transdisciplinaire de l’accompagnement dans le cadre d’un système bancaire solidaire. Rapport de recherche à la Direction Générale à la Cohésion Sociale et au Ministère Délégué à l’ESS. Under the scientific responsibility of Pascal GLEMAIN, 2012.

FLONNEAU, Mathieu and Vincent GUIGUENO (eds), De l’histoire des transports à l’histoire de la mobilité, Rennes : Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2009.

GAUTHIER, Bruno, « Des voitures et des Hommes », Cahiers François Viète, n°5, 2003, pp. 63-72.

GLEMAIN, Pascal, Microfinance sociale, Rennes : éditions Apogée, 2021.

GLEMAIN, Pascal (dirend.), Emmanuel BIOTEAU, Brigitte CHARLES-PAUVERS, Jean-Yves DARTIGUENAVE, Sigrid GIFFON and Gaël HENAFF, Les défis de la microfinance sociale face la fragilité financière et aux mobilités, Rapport de recherche au Crédit Municipal de Nantes-Angers-Rennes-TOURS, avec le soutien de la Banque de France Pays de la Loire et la Banque Populaire Grand Ouest, 2024.

HARRISON, Denis and Jacques BOUCHER, « La co-production du savoir sur l’innovation sociale », Économie et Solidarités, vol. 41, N° 1-2, 2011, pp. 3-8.

HISLOP, Donald and Carolyne AXTELL, “The neglect of spatial mobility in contemporary studies of work: the case of telework,” New Technology, Work and Employment, vol.24, n°1, 2007, pp. 34-51.

HUMBERT, Marc, Vers une civilisation de la convivialité. Rennes : éditions Goater, 2013.

ILLICH, Ivan, Énergie et équité. Paris : éditions du Seuil, 1973a.

ILLICH, Ivan, La convivialité. Paris : éditions du Seuil, 1973b.

LE BRETON, Eric, Bouger pour s’en sortir. Mobilité Quotidienne et intégration sociale, Paris : Armand Colin, Coll. « Sociétales », 2005.

LE BRETON, Eric, Mobilité, la fin du rêve ? Rennes : éditions Apogée, 2019.

LERAY, Frédéric and Raymonde SECHET Raymonde., « Les mobilités sous contraintes des mères seules avec enfant(s) : Analyse dans le cadre de la Bretagne (France) », pp. 69-88 in Philippe GERBER and Samuel CARPENTIER (dir.), Mobilités et modes de vie. Vers une recomposition de l’habiter, Rennes, PUR, 2013.

LOACKER, Bernadette and Martyna ŚLIWA “Moving to stay in the same place? Academics and theatrical artists as examplars of the mobile middle”, Organization, Vol. 23, n°5, 2016, pp. 657-679.

LUSSAULT, Michel, L’Homme spatial. La construction sociale de l’espace humain, Paris : éditions du Seuil, 2007.

LUSSAULT, Michel and Mathis STOCK, 2003, « Mobilités », in Jacques LEVY and Michel LUSSAULT (dir.), Dictionnaire de la Géographie et de l’espace habité, Paris : Belin, 2003.

MARTOUZET, Denis, « Mobilités résidentielles, parcours professionnels et déplacements quotidiens : spatialités emboîtées et construction de l’habiter », p. 49-65, in Philippe GERBER et

Observatoire de l’inclusion bancaire, Rapport annuel 2020, [https://www.banque-france.fr/system/files/2023-02/oib2020_web.pdf]

REIFNER, Ugo, « La finance sociale : des produits au service du développement communautaire et local », pp. 200-217, in INAISE, Banques et cohésion sociale, Paris : éditions Charles Léopold Mayer, 2000.

SEN, Amartya, Un nouveau modèle économique de développement. Justice, liberté, Paris : éditions Odile Jacob, 2003.

SERGOT, Bernard, Elodie LOUBARESSE and Didier CHABAULT, « Mobilités spatiales et organisation : proposition d’un agenda de recherche », Management international / International Management / Gestiòn Internacional, 22(4), 2018, pp. 53–59.

SEWELL, Graham and Laurent TASKIN, “Out of sight, Out of mind in New World of Work? Autonomy, Control, and Spatiotemporal Scaling in Telework”, Organization Studies, Vol.36, n°11, 2015, pp.1507-1529.

SHELLER, Mimi, “The new mobilities paradigm for a live sociology”, Current Sociology, Vol.62, n°6, 2014, pp. 789-811.

SHELLER, Mimi and John URRY, “The New Mobilities Paradigm”, Environment and Planning, 38 (2), 2006, pp. 207–226.

TASKIN, Laurent, « La déspatialisation – Enjeu de gestion », Revue française de Gestion, n°202, 2010, pp. 61-76.

Auteurs

Références

Pour citer cet article :

Pascal GLEMAIN - "Pascal GLEMAIN, Fostering inclusive mobilities with social microcrédit : opportunities for public social banking in France" RILEA | 2025, mis en ligne le 03/12/2025. URL : https://anlea.org/revues_rilea/7669/